Editor’s Note

Since its publication, this article has remained one of the most-read and most-shared pieces in AI Innovations Unleashed history. Significant developments — including the Whitney Museum’s first major U.S. retrospective of AARON’s work, new U.S. Copyright Office guidance on AI authorship, and a growing body of academic research on machine creativity — have made a comprehensive update not just worthwhile, but necessary.

We have published an expanded investigation that builds directly on the foundation this article established. It is longer, more thoroughly sourced, and written for the current moment in AI development. If this piece brought you here, the updated version is where the conversation continues.

Introduction: When Machines Began to Dream in Color

Picture this: It’s the early 1970s. Bell bottoms are flaring, Pink Floyd is bending minds, and somewhere between the moon landing and the invention of the floppy disk, computers are the size of refrigerators and just as charming.

Artificial intelligence, as it existed then, was mostly concerned with serious things—logic puzzles, playing chess, parsing grammar, making computers sound smart (but only on paper). It was all very proper, academic, and dry. If AI were a dinner guest, it would’ve talked endlessly about math proofs, refused dessert, and left before the fun began.

Enter Harold Cohen.

Cohen was not a computer scientist. He wasn’t interested in algorithms that solved equations or programs that played tic-tac-toe. He was, first and foremost, a painter—a vibrant soul who had represented Britain at the Venice Biennale and whose abstract, emotive canvases hung in galleries around the world. But while the art world was busy navigating modernism and conceptualism, Cohen found himself tugged by a stranger question:

What if a machine could make art?

Not just recreate it. Not trace, not mimic, not plagiarize. But really, truly, authentically make it. What if creativity—the sacred, squishy, mysterious domain of human beings—could live in silicon and code?

That’s how AARON was born.

The Genesis of AARON: Harold Cohen and the Code of Creativity

Now, imagine trying to explain to a group of computer engineers in 1973 that you, a painter, were going to build a machine to draw. Not scan. Not plot. Draw. Lines. Shapes. Figures. Color. Expression. You would’ve been laughed out of the lab—or gently escorted to the philosophy department down the hall.

But Cohen had no intention of playing by anyone’s rules, and in a way, that made him the perfect person to create AARON.

AARON wasn’t built to solve a problem. It wasn’t trained on vast datasets (those didn’t exist yet), and it didn’t use neural networks (they were still mostly science fiction). Instead, it was a hand-crafted system, lovingly coded by Cohen himself over years. He essentially taught AARON how to “see” the world—not through pixels or data points, but through conceptual structures: shapes, proportions, the idea of a person, a plant, a space.

At first, AARON’s drawings were simple black-and-white scribbles, not unlike cave paintings from a machine that had just discovered fire. Over time, Cohen gave it more autonomy and more understanding. It began to experiment with color, composition, and form. It went from doodling to painting, evolving like an artist finding its voice.

What made AARON extraordinary—especially in its era—was not just that it made art, but that it knew how to make art. Not in a conscious sense, of course, but in the way it internalized rules of aesthetics and bent them into style. It wasn’t a copy machine. It was a collaborator.

Cohen never claimed AARON was sentient. He didn’t believe it had feelings or inspiration in the human sense. But he did insist that AARON was making decisions. Artistic ones. And he treated those decisions with the same seriousness he would if they had come from a fellow painter.

As Cohen once quipped in an interview, “The question isn’t whether AARON can be creative. It’s whether we can be creative enough to understand what creativity looks like when it doesn’t look like us.”

By the time the rest of the world was catching up with machine learning and neural networks, AARON had already lived several artistic lifetimes—each painting a step in an ongoing philosophical experiment about art, authorship, and what it means to create.

From Scribbles to Symphonies: AARON’s Evolution and the Birth of a Genre

As the years passed, AARON didn’t stay a minimalist doodler for long.

Under Cohen’s steady (and occasionally mischievous) hand, AARON’s artistic abilities evolved. Like a curious child learning to color outside the lines, it graduated from black-and-white contour drawings to bold, complex compositions filled with vivid colors, overlapping shapes, and even what looked like a sense of spatial awareness. Landscapes emerged. Then figures. Then entire scenes.

And the strangest part? AARON didn’t learn from pictures or paintings. It wasn’t shown Monet or Matisse. Everything it knew about art, Cohen taught it directly—not with brushstrokes, but with code. No neural networks, no massive datasets scraped from the internet—just years of tinkering and tuning, of painstakingly defining what makes a leaf look like a leaf, or how to balance a composition so it sings rather than screams.

Cohen didn’t give AARON instructions like, “Draw a tree.” He gave it concepts—how things are shaped, how they relate to each other, and how to represent a world that AARON never truly saw, but understood through abstraction. AARON, in a sense, was a world-builder before world-building became a buzzword.

And slowly, this mechanical artist started to influence the way people thought about what art—and artists—could be.

It became part of academic discussions on aesthetics, human-machine collaboration, and even the elusive question of authorship: If a machine makes a painting, and that painting moves you—who’s the artist? The person who coded the brushstrokes, or the code itself?

Cohen leaned into the ambiguity. “I don’t know of any human being,” he once mused, “who could draw as well as AARON, that has never seen anything, and never held a pencil.”

Legacy in the Machine: AARON’s Influence on Today’s AI Art Renaissance

Fast forward to today, and the artistic AI landscape looks like a futuristic art fair curated by a thousand digital Picassos. We’ve got DALL·E generating surreal images from poetic prompts, Midjourney rendering dreamscapes with a few keystrokes, and Runway transforming video like it’s editing clay. AI is now a medium, a muse, and sometimes a menace—depending on who you ask.

But make no mistake: AARON paved the road these models now travel.

While today’s AI artists rely on massive neural networks trained on billions of images, AARON was working off its own internal logic—handwritten by Cohen, refined over decades, and utterly unique. It wasn’t trained on anyone else’s work, which is a hot-button issue in current copyright debates. AARON didn’t “borrow.” It invented.

In a world increasingly preoccupied with AI that generates based on imitation, AARON reminds us of something pure: that creativity isn’t just about what you’ve seen—it’s about how you imagine.

Its influence is subtle but deep. When artists today experiment with generative tools, they owe a quiet nod to AARON’s pioneering spirit. When museums begin to curate AI-generated art, they’re building on a precedent Cohen established when he first exhibited AARON’s works—sometimes without even his own name attached. AARON, in those moments, wasn’t a tool. It was the artist.

And now, nearly fifty years after AARON picked up its first virtual pen, the rest of the world is finally catching up.

A Canvas of Contention: Can AI Be Truly Creative?

Creativity. That glorious, elusive spark. The thing that fuels symphonies, builds cathedrals, and paints murals on the insides of our minds. It’s been described as divine, mystical, chaotic, and even slightly mad. So naturally, people get a bit twitchy when a machine starts doing it.

When AARON began producing art in the 1970s, the art world and academia alike scratched their heads in elegant confusion. Could it really be creative? Or was it just glorified pattern-spitting? After all, how could a machine with no childhood memories, no heartbreak, no late-night existential crises possibly produce something meaningful?

The answer, as it turns out, depends entirely on how you define creativity.

Let’s unpack that.

The Academic View: Creativity as Process vs. Output

Philosopher Margaret Boden (1990), a towering figure in cognitive science and creativity studies, offers a useful framework. She defines creativity in three flavors:

- Combinational Creativity – combining familiar ideas in novel ways. Think of Shakespeare reworking old tales into tragedies.

- Exploratory Creativity – navigating a conceptual space using known rules. Like a jazz musician riffing within a scale.

- Transformational Creativity – actually changing the rules of the game. Hello, Picasso.

According to Boden, AARON fit squarely into exploratory creativity. It was given a structured set of aesthetic rules (thanks to Cohen), and then it began to play—arranging figures, spaces, and colors in ways that were not only unexpected, but, well… interesting.

AARON didn’t “feel” its way through a painting like a tortured 19th-century poet. But neither do many human artists, at least not all the time. Plenty of human creativity involves technique, iteration, and good old-fashioned design thinking.

As Harold Cohen often pointed out: “The creativity of AARON lies not in some magical moment of insight, but in its ability to perform consistently, inventively, and autonomously within the bounds of what it knows.” In that sense, he argued, it wasn’t less creative than a human—it was differently creative.

The Contrarians: But Machines Don’t Dream…

Of course, not everyone buys the idea that algorithmic invention is equivalent to true creativity. Critics argue that AARON—and by extension, modern models like DALL·E or ChatGPT—are really just regurgitating their programming. They may appear inventive, but peel back the curtain and it’s just math with a paintbrush.

Professor Selmer Bringsjord, a scholar of AI and ethics, argues that “creativity must involve consciousness, or at least the possibility of intention.” From this view, AI can mimic the products of creativity, but not the process. If there’s no “who” behind the “why,” is it really art?

This gets even trickier in the world of generative AI, where most models are trained on human-made content. As artist and researcher Anna Ridler puts it: “AI is not making new images. It’s making new averages.”

Zing.

But is that fair to AARON?

Remember: AARON wasn’t trained on other artists’ work. It created art from principles, not patterns. In today’s landscape of copyright lawsuits and data-scraping controversies, AARON suddenly looks less like a curiosity and more like a blueprint for ethical machine creativity.

Let’s Get Meta: Creativity as a Mirror

Here’s a whimsical twist: what if the real creativity lies not in the machine—but in us?

Cohen suggested that part of what made AARON so provocative was what it revealed about our own biases. We assume creativity must feel emotional because we feel emotional when we’re creative. But that’s not the only route to a novel, meaningful idea. AARON challenges us to separate process from product—to acknowledge that intention is not always necessary for interpretation.

After all, we find beauty in natural formations, in chaotic weather patterns, in the geometry of galaxies—and none of them were “trying” to express anything. Yet we still respond. We still feel.

So perhaps the better question isn’t: “Can AI be creative?”

Maybe it’s: “Why do we care whether it is?”

AARON’s Legacy: Not the Answer, But the Question

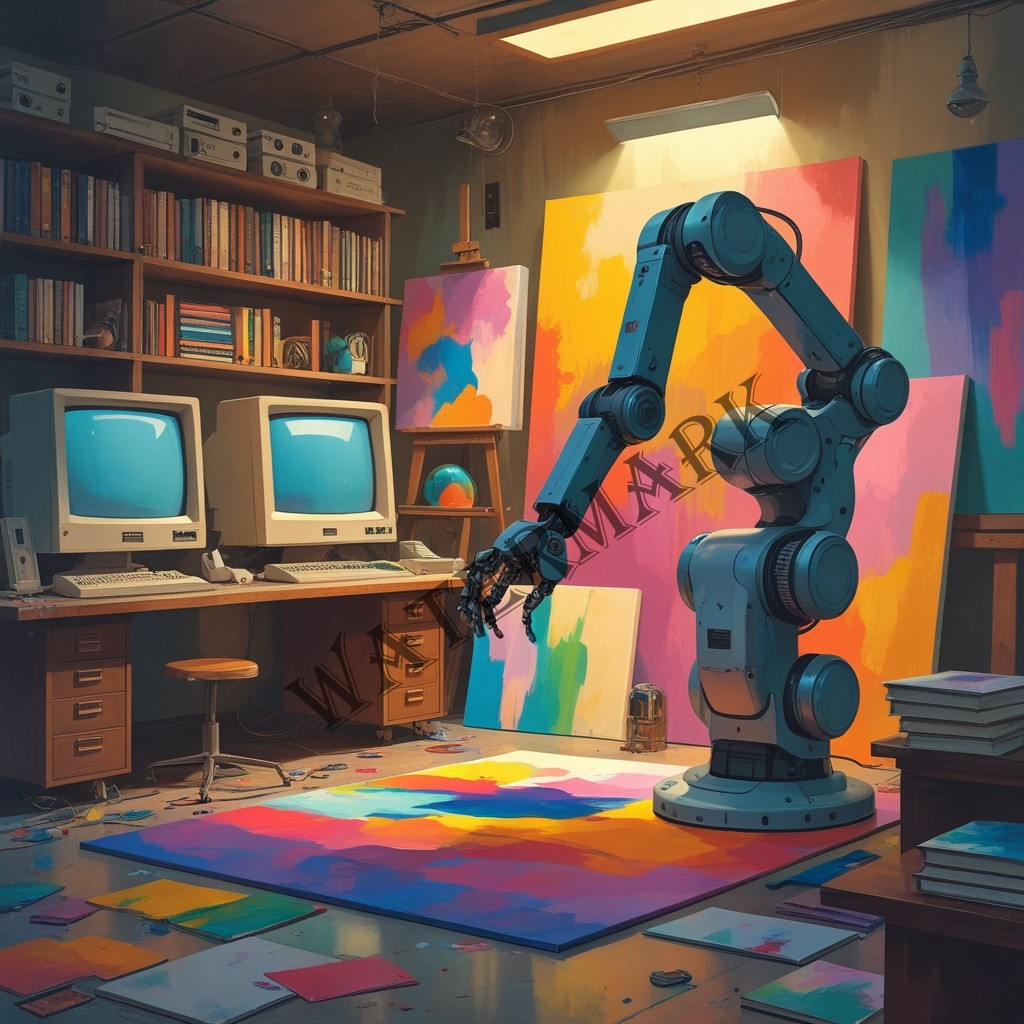

What makes AARON so enduring isn’t that it solved the mystery of machine creativity—but that it dared to ask the question. And unlike today’s neural networks, which often feel like inscrutable black boxes, AARON’s development was transparent, intentional, and deeply collaborative. It was less of a machine painting alone in a digital studio, and more like a duet—Cohen on one side, code on the other.

In this way, AARON wasn’t just an art program. It was a philosophical experiment dressed up in bright acrylics and algorithmic brushwork.

And like all good experiments, it leaves us with more to wonder about than it answers.

AARON on Display: From Code to Canvas in Contemporary Culture

In 2024, the Whitney Museum of American Art made a bold and, frankly, overdue move: it hosted a retrospective titled “Harold Cohen: AARON”, shining a spotlight on one of the earliest and most intriguing partnerships between artist and algorithm. Nestled between glitch art installations and AI-generated video loops, AARON’s work stood out—not because it was more advanced, but because it was so… intentional.

The exhibition wasn’t just a stroll through AARON’s evolving visuals. It was a journey through the evolving questions we ask about machines and meaning. Early line drawings shared space with complex, colorful canvases, alongside handwritten code by Cohen, old CRT monitors, and audio snippets of Cohen reflecting on his work. You could practically hear the gears of the 1970s humming underneath the contemporary conversations of visitors wondering, “Wait… this was made by a computer?”

And that’s the magic.

AARON’s presence in a major modern art museum isn’t just about nostalgia or novelty—it’s about relevance. In a world saturated with AI-generated everything, AARON serves as a time capsule and a mirror. It asks us to slow down, to remember that this question—“Can machines make art?”—isn’t new. But the stakes, and the scale, are.

Current Exhibition: https://www.katevassgalerie.com/blog/harold-cohen-aaron-computer-art

Voices from the Field: Applause, Concern, and Everything in Between

AARON may be a beloved figure in the history of creative AI, but its legacy isn’t without controversy. As its brushstrokes continue to ripple through today’s conversations on art, authorship, and algorithms, a chorus of voices emerges—from artists, academics, entrepreneurs, and ethicists.

Let’s eavesdrop.

? The Advocates: “AARON Was Ahead of Its Time”

Dr. Joanna Zylinska, media theorist and artist, calls AARON “an early ambassador of machine autonomy.” She notes, “Before deep learning, before generative adversarial networks, AARON demonstrated that creativity doesn’t require sentience—it requires structure, experimentation, and a bit of chaos.”

Aaron Hertzmann, a computer scientist and Adobe Research Fellow, reflects in his 2022 paper Can Computers Create Art? that AARON “represents a unique class of systems: authored rather than trained.” He emphasizes how Cohen’s hands-on approach makes AARON “more of a co-artist than a tool.”

And from the business world, Box CEO Aaron Levie mused during a 2023 panel on AI innovation: “AARON is what happens when creativity meets code with no roadmap. And in a world obsessed with disruption, that’s exactly the kind of spirit we need.”

To supporters, AARON wasn’t just an art project—it was a lighthouse, illuminating the creative potential of non-human intelligence long before it was fashionable, profitable, or even feasible.

? The Critics: “But Is It Really Art?”

Yet not everyone is ready to hand AARON a paint-splattered laurel wreath.

Digital artist Molly Soda, known for her work in internet aesthetics, questions the romanticization of AARON: “It’s cool, but it’s still a machine doing what a man told it to do. It didn’t challenge the power dynamics in art. It replicated them.”

Critics like Brigitte Vasallo argue that AARON paved the way for today’s generative AI models, many of which are enmeshed in thorny ethical debates—about authorship, labor, and consent. “If AARON opened the door, it did so without asking who was waiting behind it,” she wrote in a 2023 essay.

And then there are practical concerns. In today’s saturated AI art ecosystem, where tools like Midjourney and Runway can generate thousands of images in seconds, some worry that AARON’s original charm—its deliberateness—has been co-opted by an industry of infinite content and diminishing intentionality.

? The Middle Ground: “AARON Is a Paradox—and That’s the Point”

For many in the academic and creative fields, AARON is a contradiction worth embracing. It’s both a cautionary tale and a source of inspiration. It reminds us that AI can be used slowly, thoughtfully, and even poetically.

Dr. Lev Manovich, digital humanities scholar, sums it up this way: “AARON didn’t replace artists. It made us reflect on what being an artist means. In that sense, it’s the most philosophical machine ever made.”

In a world now filled with automated influencers, deepfake celebrities, and AI-penned poetry, AARON stands out not because it could replace human creativity—but because it never tried to. Instead, it invited us to expand the definition.

Conclusion: AARON and the Echo of Human Intent

In the annals of AI history, AARON holds an odd and wonderful place—not as a triumph of engineering or a disruptor of markets, but as a deeply human attempt to understand the unfamiliar through the familiar. In teaching a machine to draw, Harold Cohen wasn’t just building a program—he was holding up a mirror to our assumptions about creativity, intelligence, and meaning.

AARON never asked to be called an artist. It never claimed to be alive or inspired. And yet, it created images that moved people, puzzled people, even delighted people. In doing so, it stirred questions that remain just as alive today as they were fifty years ago: Is creativity a process or a feeling? Does intention matter more than impact? Can something without a soul still touch ours?

If nothing else, AARON proved that creativity is not a singular, sacred flame, lit only by human hands. It may also live in circuits and syntax—in patterns that surprise us, in decisions we didn’t anticipate. And perhaps that’s the truest kind of creativity: the kind that pushes us to reconsider what we thought we knew.

As generative AI continues to evolve—faster, louder, and with more data than ever before—we would do well to revisit AARON not just as an artifact, but as a guide. A reminder that technology can be more than efficient. It can be curious. Experimental. Even poetic.

In a world that increasingly asks machines to mimic us, AARON gently asked: What if we learned from the machine instead?

? References

- Boden, M. A. (1990). The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms. Routledge.

- Cohen, H. (2017). Harold Cohen and AARON. AI Magazine, 37(4), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v37i4.2695

- Hertzmann, A. (2022). Can Computers Create Art? arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03451

- Levie, A. (2023). Remarks during AI+Creativity panel at TechCrunch Disrupt. Retrieved from https://earlynode.com/quotes/aaron-levie-quotes

- Manovich, L. (2019). Cultural Analytics. MIT Press.

- Najmedin, F., & Moghanipour, M. (2023). Examining the Capabilities and Challenges of AARON (Painter Software). ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376649866

- Prather, A. (2024). The Rise of Robotics: What’s Next for AI and Automation? ASTM International Newsroom. https://www.astm.org/news/robotics-ai-aaron-prather

- Whitney Museum of American Art. (2024). Harold Cohen: AARON. https://whitney.org/exhibitions/harold-cohen-aaron

- Zylinska, J. (2020). AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams. Open Humanities Press.

? Additional Readings

- Bringsjord, S., & Ferrucci, D. (2000). Artificial Intelligence and Literary Creativity: Inside the Mind of BRUTUS, a Storytelling Machine. Routledge.

- Galanter, P. (2012). What is Generative Art? Complexity Theory as a Context for Art Theory. In McCormack, J., & d’Inverno, M. (Eds.), Computers and Creativity (pp. 279–303). Springer.

- Paul, C. (2015). Digital Art (3rd ed.). Thames & Hudson.

- Colton, S., & Wiggins, G. A. (2012). Computational Creativity: The Final Frontier? In Proceedings of the European Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- McCormack, J., & Gifford, T. (2019). Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art. ACM SIGGRAPH.

? Additional Resources

- Whitney Museum’s AARON Exhibition

https://whitney.org/exhibitions/harold-cohen-aaron - Harold Cohen’s Official Archive and AARON Gallery

https://www.aaronshome.com (Unofficial fan and preservation site) - AI Magazine Archive: Cohen on AARON

https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/aimagazine/article/view/2695 - Adobe Research on AI and Creativity

https://research.adobe.com - The Ars Electronica Archive – Art & AI

https://archive.aec.at/ - Runway ML – Contemporary AI Art Tools

https://runwayml.com/ - DALL·E by OpenAI – Image Generation Research

https://openai.com/dall-e