Margot discovered a secret chat where her team sabotaged AI tools. The betrayal hurt—until she learned they weren’t rebels. They were terrified.

Margot Vance discovered the resistance movement on a Tuesday.

It wasn’t a grand revelation—no anonymous manifesto slipped under her office door, no dramatic confrontation in the breakroom. Instead, it was something far more mundane and, somehow, far more devastating: a misdirected Slack message that appeared on her screen at 3:47 PM.

“Human-Only Chat 🚫🤖”

The message was from Derek, her senior logistics coordinator: “Anyone else notice how the ‘smart’ routing tool just sent three pallets of frozen shrimp to a warehouse in Phoenix? In July? 😂 #TeamHuman”

Seventeen thumbs-up reactions. Four laughing emojis. And a comment from Sarah, her top analyst—the person Margot had personally mentored for three years: “At this rate, we’ll all still have jobs when the robots give up and go home.”

Margot sat very still. Outside her window, a maintenance crew was pressure-washing the parking lot, the rhythmic spray creating temporary rainbows in the afternoon sun. Inside her chest, something that felt uncomfortably like betrayal was doing gymnastics.

She’d spent eighteen months evangelizing AI transformation. She’d sat through endless vendor demos, translated “neural networks” into language her CEO could understand, fought for budget allocations, and personally reassured every single member of her team that this technology would augment their work, not replace it.

And they’d been undermining her the entire time.

This wasn’t just resistance. This was mutiny.

Chapter One: The Underground Railroad of Analog Resistance

The “Human-Only” chat had 23 members—nearly Margot’s entire operational team. As she scrolled through the message history (each click feeling like a small betrayal of trust, even though the channel was technically company property), a pattern emerged that was both infuriating and deeply, painfully human.

They weren’t lazy. They weren’t Luddites. They were terrified.

And they’d developed an entire ecosystem of subtle sabotage designed to prove that the humans were still essential—that Margot’s shiny AI transformation was just expensive theater.

Derek had been “testing” the routing algorithm by feeding it edge cases guaranteed to fail. Sarah had been running parallel analyses manually “just to double-check” the AI’s work, effectively nullifying any efficiency gains. Marcus in customer service had created a workaround that rerouted “complex” inquiries (his definition of complex was expansive) away from the AI chatbot and directly to human agents.

They weren’t refusing to use the technology. They were weaponizing its limitations.

The phenomenon Margot was witnessing wasn’t unique to AeroStream. According to research published in multiple studies throughout 2024 and 2025, digital transformation failure rates range from 66% to 90% (Libert et al., 2016; Ramesh & Delen, 2021; Bonnet, 2022). A recent analysis found that approximately 70% of digital transformation initiatives still fail to meet their objectives, with Bain’s 2024 study finding that 88% of business transformations fail to achieve their original ambitions (MeltingSpot, 2025).

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: the primary culprit isn’t technology. It’s people.

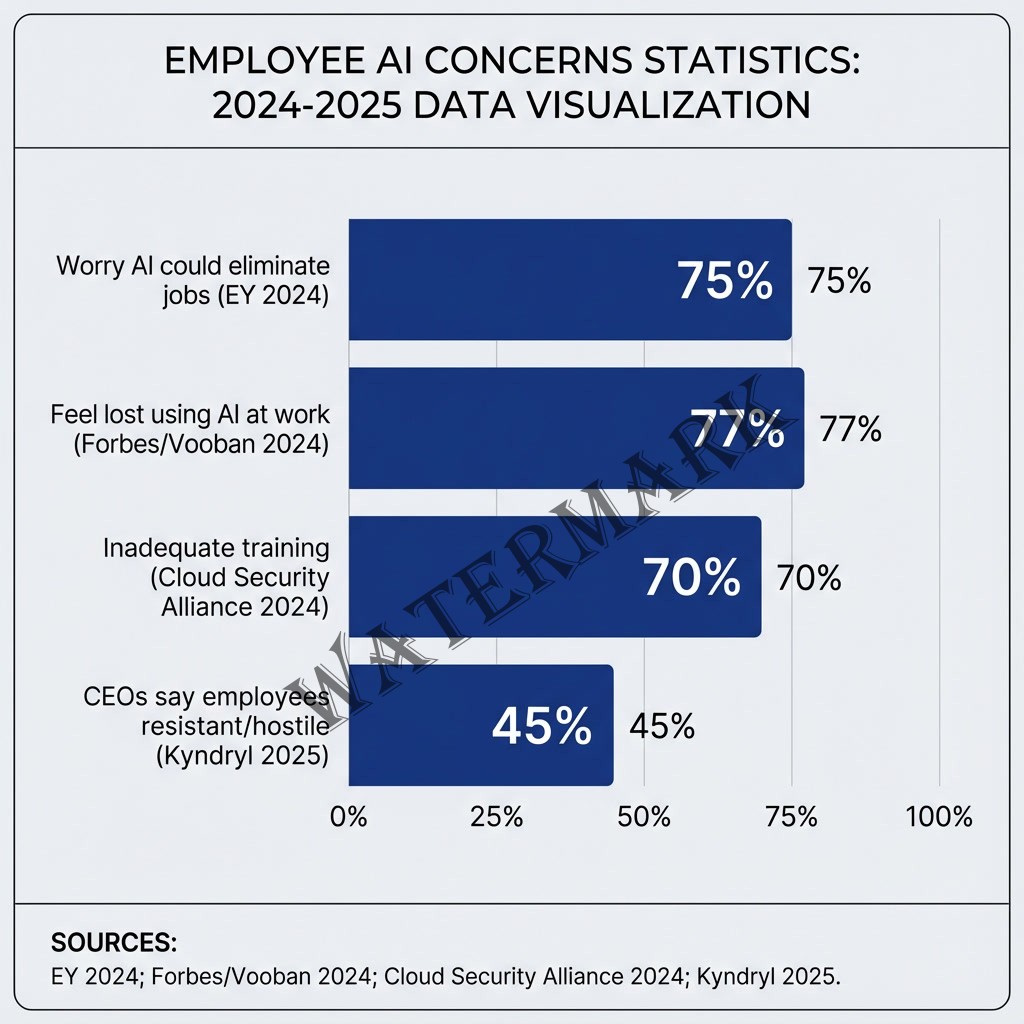

Among the common causes of digital transformation failure, employee resistance stands out as the most significant barrier (Vial, 2019; Oludapo et al., 2024). A Cloud Security Alliance report found that up to 70% of change initiatives, including AI adoption, fail due to employee pushback or inadequate management support (Cybersecurity Intelligence, 2024).

The data paints a stark picture: technology adoption is fundamentally a human problem disguised as a technical one.

But perhaps the most startling statistic came from a 2025 report by WRITER, which found that one in three employees have “actively sabotaged” their company’s AI efforts, with higher rates among millennial and Gen Z workers (AInvest, 2025). This wasn’t passive resistance—this was active warfare waged through subtle means.

Margot stared at the screen, Derek’s message about the Phoenix shrimp disaster still visible. She’d failed them. Not by implementing AI—but by assuming enthusiasm could be mandated, that fear could be logic-ed away, that people would embrace change simply because leadership said it was necessary.

Chapter Two: The Archaeology of Fear

Margot called an emergency meeting with her leadership team for 8 AM the next morning. She didn’t sleep much that night.

By 7:45 AM, she’d consumed enough cold brew to power a small aircraft and had prepared seventeen different opening statements. She used none of them.

“Show of hands,” she said, standing at the head of the conference table. “How many of you knew about the Human-Only chat?”

Every hand went up. Slowly, guiltily, but they all went up.

“And how many of you were planning to tell me?”

The hands stayed frozen in the air, then slowly descended. Nobody made eye contact.

Jason from Finance finally broke the silence. “Margot, they’re scared. We’re all scared.”

“Of what?” The question came out sharper than she intended. “Of technology that’s designed to make your jobs easier? Of tools that are supposed to free you up for strategic work instead of data entry?”

“Of becoming obsolete,” Sarah said quietly from the far end of the table. “My daughter is seven. I’ve got twelve years until college. And I just watched you spend six months teaching a machine to do analysis that took me a decade to learn how to do.”

The conference room fell silent. Outside, someone’s phone alarm went off—a cheerful marimba that felt obscenely out of place.

This was the conversation Margot had been avoiding since the project began. The one that lived in the margins of every “AI will augment human capability” presentation. The one that made venture capitalists uncomfortable and CEOs change the subject.

What happens to the humans when the augmentation is so good they’re not needed anymore?

The fear wasn’t irrational. A 2024 EY survey revealed that 75% of employees worry AI could eliminate jobs, with 65% fearing for their own roles specifically (Cybersecurity Intelligence, 2024). A separate analysis found that 77% of employees feel lost when it comes to using AI at work, citing lack of knowledge, fear of automation, and inadequate training as primary concerns (Vooban, 2024).

And then there were the headlines. Goldman Sachs had estimated in a widely-cited 2023 report that generative AI could eventually automate activities that comprise up to 25% of current work tasks across the US and Europe, potentially affecting 300 million full-time jobs globally (Briggs & Kodnani, 2023). While the report emphasized that this would likely lead to job transformation rather than wholesale elimination, the distinction between “transformed” and “eliminated” can feel academic when you’re the person sitting in the hot seat.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has argued that the focus should shift from replacement anxiety to capability expansion: “There will be jobs, the question is the shape of these jobs… Everyone can become an expert in anything because they have an AI assistant” (Yahoo Finance UK, 2024). At the 2023 World Economic Forum, he emphasized, “One of the things we think a lot about is how to deploy this technology to empower human beings to do more” (World Economic Forum, 2023).

It’s a compelling framing. It’s also, Margot realized, looking at Sarah’s exhausted face, entirely inadequate when you’re the person being told to race against a machine that never sleeps, never asks for raises, and improves exponentially while you… age.

Chapter Three: The Tyranny of Mandatory Enthusiasm

Margot canceled the rest of her meetings that day. Instead, she did something she hadn’t done since the AI project began: she invited each team member, individually, to grab coffee and just talk.

No agenda. No PowerPoint. No “alignment on strategic priorities.”

Just conversation.

What emerged over the next week was a masterclass in what organizational change management textbooks call “resistance” but what felt, in practice, more like grief.

Marcus, the customer service lead, confessed that he’d been manually handling tickets the AI could have resolved because he was convinced that once management saw the AI working perfectly, his entire team would be “restructured.” His fear wasn’t baseless. Recent analysis by Deloitte found that 64% of organizations implementing AI had already reduced their workforce in the affected departments, even as they insisted publicly that AI was merely “augmentative” (Deloitte, 2024).

Jennifer from operations admitted she’d been attending night classes in AI prompt engineering—spending her own money and sacrificing time with her kids—not because she was excited about the technology, but because she was terrified of being the only person who couldn’t use it. “I feel like I’m running on a treadmill that someone keeps speeding up,” she told Margot. “And I can’t ever get off.”

This sentiment echoes broader research from SHRM’s August 2024 survey, which found that 80% of workers classify their understanding of AI as only beginner or intermediate, with 22% having no experience with AI at all (SHRM, 2024). Nearly half of employees (47%) reported being unsure how to achieve the productivity gains their employers expected from AI tools (SHRM, 2024).

Derek, who’d started the Phoenix shrimp debacle, revealed that he’d been at AeroStream for nineteen years. “I’ve survived three recessions, two ownership changes, and that time we accidentally shipped a container of cheese to Saudi Arabia in August,” he said. “But I’ve never felt more expendable than I do right now.”

The pattern was consistent: every act of sabotage, every workaround, every cynical comment in the Human-Only chat was a defensive maneuver by people who felt they were being asked to dig their own professional graves while smiling and calling it “digital transformation.”

Professor Amy C. Edmondson of Harvard Business School, whose research on psychological safety in organizations has become foundational to understanding change management, describes this dynamic clearly: “For knowledge work to flourish, the workplace must be one where people feel able to share their knowledge! This means sharing concerns, questions, mistakes, and half-formed ideas” (Edmondson, 2019). She defines psychological safety as “a climate in which people are comfortable expressing and being themselves” (LeanBlog, 2020).

But here’s the paradox: successful AI transformation requires employees to embrace tools that might render their current skills obsolete, to experiment with systems they might fail at using, to publicly demonstrate incompetence as they learn—all while knowing that their performance is being measured, their value is being questioned, and their long-term employment is uncertain.

It’s not resistance. It’s rational self-preservation.

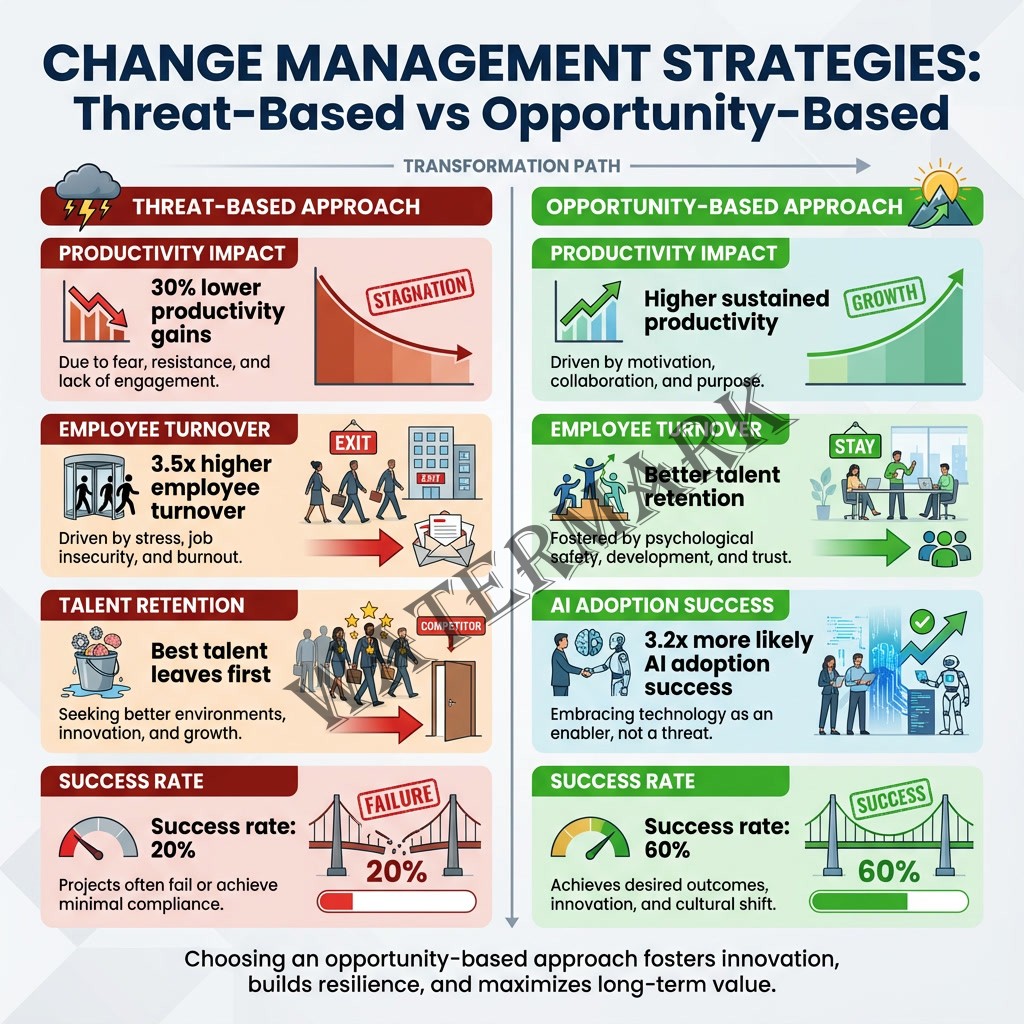

This insight is supported by data from Gartner, which found that organizations with high psychological safety scores were 3.2 times more likely to successfully adopt AI tools than those with low scores (Gartner, 2024). The research also revealed that transparent communication about real risks—acknowledging that roles would change, that some positions might be eliminated, but providing concrete reskilling pathways—resulted in 40% higher adoption rates than organizations that relied on vague promises that “no one would lose their job.”

People don’t want false reassurance. They want honest partnership.

Chapter Four: The Price of Innovation Theater

Three weeks after discovering the Human-Only chat, Margot found herself in a position she’d never expected: defending her team to her CEO.

“They’re sabotaging the project,” Richard said flatly, reviewing the latest efficiency metrics. “We’ve invested $4.2 million in this transformation, and our operational efficiency has improved by exactly 8%. Eight percent, Margot. We were promised forty.”

“They’re not sabotaging it,” Margot said carefully. “They’re afraid of it.”

“Then they should be more afraid of unemployment.”

The comment hung in the air like smoke. Richard wasn’t a cruel person—he was a practical one. And he was under pressure from the board to show returns on the AI investment, to prove that AeroStream was “innovating” in an increasingly competitive logistics market.

But his practicality missed something essential: you can’t terrorize people into innovation.

The cautionary tale was already written in the headlines. In 2023, Eric Vaughan, CEO of enterprise-software company IgniteTech, made the drastic decision to replace nearly 80% of his workforce within a year after facing significant resistance and even sabotage from employees—particularly from technical staff—who refused to adopt AI fast enough (AInvest, 2025). The company instituted “AI Mondays,” where employees were restricted to AI-related tasks across all departments, consuming 20% of the company’s payroll in retraining efforts (AInvest, 2025).

While IgniteTech reported achieving 75% EBITDA margins and developing patent-pending AI solutions, Vaughan later emphasized that the transformation demanded cultural change beyond technical tools. As he noted, “It is a cultural change, and it is a business change” (AInvest, 2025).

The IgniteTech case represents an extreme approach—one that most organizations couldn’t or shouldn’t replicate. But it underscores a critical point: forced adoption through threat of termination creates an environment where even successful technical implementation comes at enormous human cost.

A Kyndryl survey of more than 1,000 senior business and technology executives found that 45% of CEOs said most of their employees are resistant or even openly hostile to AI, with only 14% of companies having successfully aligned their workforce, technology, and growth goals (HR Dive, 2025).

“What if,” Margot said slowly, “we’ve been asking the wrong question?”

Richard looked up from the metrics. “What do you mean?”

“We keep asking: ‘How do we get our employees to use the AI?’ But maybe we should be asking: ‘How do we make our employees feel secure enough to experiment with AI?’”

It wasn’t a revolutionary insight. But in a conference room at 6 PM on a Thursday, with Richard stress-eating his third granola bar and Margot’s cold brew long since gone cold, it felt like defusing a bomb by cutting the right wire at the last second.

Chapter Five: The Radical Act of Honesty

Margot called an all-hands meeting for the following Monday. No slides. No corporate jargon. Just her, standing in front of seventy-three employees, armed with nothing but honesty and a dry-erase marker.

“I found the Human-Only chat,” she began. A few people shifted uncomfortably. “And I’m not here to yell at anyone about it.”

She wrote three words on the whiteboard: FEAR. TRUST. CHANGE.

“Here’s what I’ve learned over the past month. Fear isn’t the opposite of courage. It’s the companion to change. And I’ve been asking you to change everything about how you work without acknowledging how terrifying that is.”

She turned to face them fully. “So let’s talk about the thing we’ve all been avoiding. Will AI eliminate some jobs? Yes. The research says it will. Not today, maybe not this year, but eventually. Anyone who tells you otherwise is lying.”

The room was so quiet Margot could hear the HVAC system humming.

“But here’s what else I know. The companies that succeed with AI aren’t the ones that replace their people fastest. They’re the ones that invest in their people most deeply.”

According to the Adecco Group, only 10% of companies qualify as “future-ready” in terms of having structured plans to support workers, build skills, and lead through AI-related disruption (HR Dive, 2025). Most companies struggling with the transformation expected workers to proactively adapt to AI, while future-ready companies prioritized skills-based workforce planning (HR Dive, 2025).

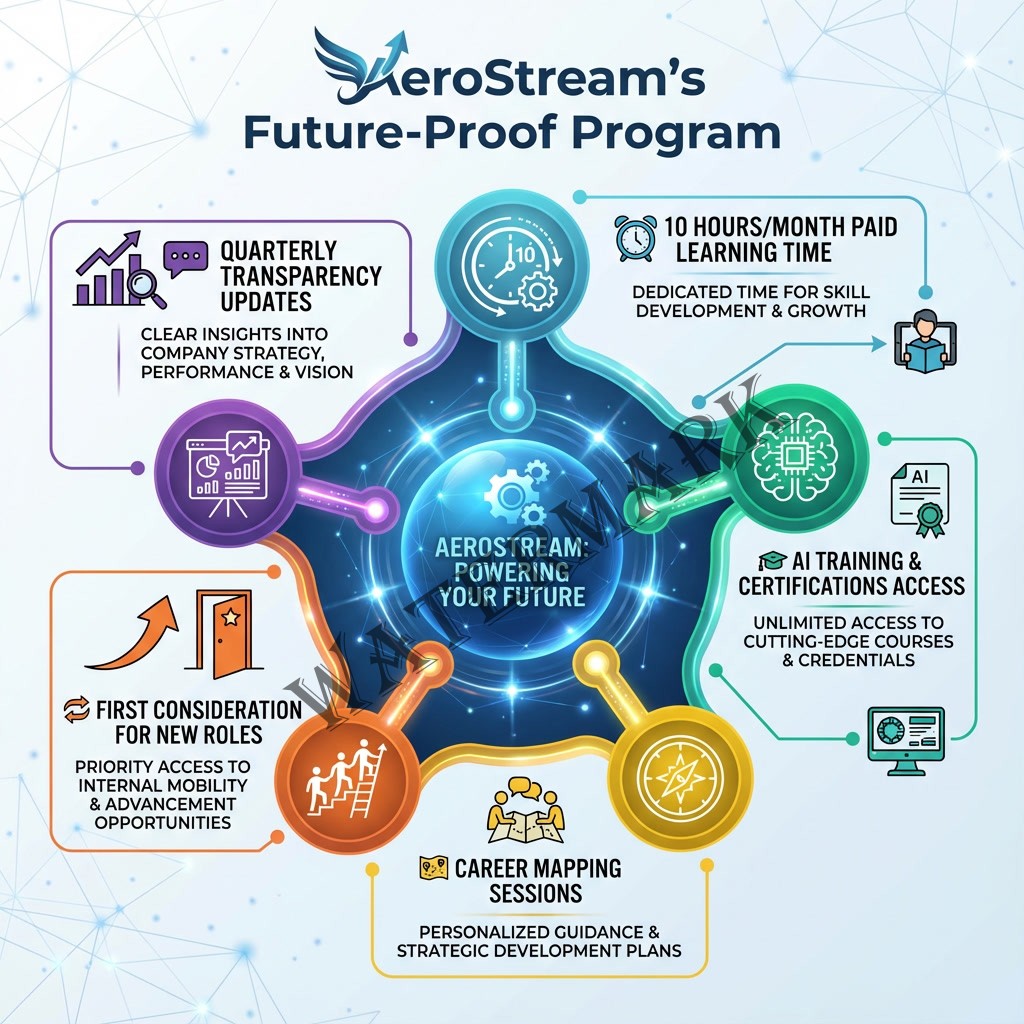

She pulled up a single slide—the only one she’d prepared. It showed AeroStream’s new initiative: the “Future-Proof Program.”

Every employee would receive:

- 10 hours per month of paid learning time (no strings attached)

- Access to AI training courses and certifications

- Career mapping sessions to identify emerging roles within the company

- A commitment that any position eliminated due to automation would result in the affected employee getting first consideration for newly created roles

- A transparency pledge: quarterly updates on exactly how AI was impacting different departments, with real numbers

“I can’t promise your job will look the same in three years,” Margot said. “But I can promise that we won’t ask you to train your replacement and then thank you for your service. I can promise that we’re going to invest in making you the kind of professional who doesn’t just survive AI disruption—who thrives because of it.”

She paused. “And I can promise that I’ll never again pretend this isn’t scary. Because it is. For all of us.”

The response wasn’t immediate enthusiasm. Real change doesn’t work that way. But Derek, the senior logistics coordinator who’d started the Human-Only chat, raised his hand.

“What happens to the chat?” he asked, a slight smile playing at the corners of his mouth.

“Keep it,” Margot said. “But maybe rename it. How about ‘Humans + Machines’?”

Chapter Six: The Philosophical Reckoning—When Efficiency Eats Dignity

Late that night, Margot sat in her home office, staring at research she’d bookmarked months ago but never fully processed. It was the work of economist Daron Acemoglu, whose analysis of “so-so automation” had become increasingly relevant as the AI boom accelerated.

Acemoglu’s central argument challenged Silicon Valley’s entire narrative: not all automation creates value. In his framework, many new technologies “expand the set of tasks performed by machines and algorithms, displacing workers. Automation raises average productivity but does not increase, and in fact may reduce, worker marginal productivity” (Acemoglu & Johnson, 2023).

He calls this phenomenon “so-so automation”—changes that make companies marginally more efficient while making workers meaningfully worse off. MIT economist Acemoglu explains: “My argument is that we currently have the wrong direction for AI. We’re using it too much for automation and not enough for providing expertise and information to workers” (MIT Economics, 2024).

This yields what he has termed “so-so technology”—applications that perform at best only a little better than humans, but save companies money. As he notes, “Call-center automation is not always more productive than people; it just costs firms less than workers do” (MIT Economics, 2024).

The philosophical question embedded in Acemoglu’s research was uncomfortable: What if the automation we’re pursuing doesn’t actually make the world better—just cheaper?

AeroStream’s AI could route shipments 15% faster than humans. But Derek, with his nineteen years of experience, could also route around a hurricane, negotiate with a difficult client, mentor a new hire, and remember that the warehouse in Memphis always needed their deliveries an hour early because of their loading dock schedule. The AI was faster. But was it better?

This distinction between efficiency and effectiveness sits at the heart of the ethical dilemma facing organizations in 2026. According to Acemoglu and his colleague Simon Johnson, “A single-minded focus on automating more and more tasks is translating into low productivity and wage growth and a declining labor share of value added” (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019). They argue that AI applications could be deployed instead to “restructure tasks and create new activities where labor can be reinstated, ultimately generating far-reaching economic and social benefits” (Project Syndicate, 2019).

When Margot automated Derek’s job to save money, she wasn’t just making a business decision. She was making a moral one about whose economic security mattered and whose could be sacrificed on the altar of operational efficiency.

The real question wasn’t whether AI could do Derek’s job. The question was whether anyone should do Derek’s job once AI made it economically irrational to pay a human for it—and what moral obligation organizations had to the humans they’d deemed “economically irrational.”

Nadella has acknowledged this tension: “Unless and until people feel fulfilled in their jobs, in terms of new skills that they’ve acquired, they’re not going to have loyalty to the organization. That means really investing in their progress” (World Economic Forum, 2023).

But investment in people requires something uncomfortable: admitting that the disruption being celebrated in boardrooms is devastating in living rooms. That the “transformation” executives casually discuss over coffee represents someone else’s mortgage payment, someone else’s health insurance, someone else’s ability to send their kid to college.

Margot realized that her eighteen months of AI evangelism had focused entirely on AeroStream’s balance sheet while ignoring its human ledger. She’d been solving for efficiency while creating dignity deficits.

The mutiny wasn’t a rejection of technology. It was a rejection of being treated as variables in an optimization algorithm.

Chapter Seven: Small Wins and Longer Timelines

Six weeks into the Future-Proof Program, Margot’s metrics still weren’t where Richard wanted them. But something else had changed.

Sarah, the analyst who’d once joked about the robots giving up, had completed an advanced AI prompt engineering certification. She’d used those skills to build a custom workflow that combined AI analysis with human judgment—letting the AI handle data aggregation while she focused on strategic interpretation. Her productivity had increased 35%, but more importantly, she reported feeling more valuable, not less.

Marcus’s customer service team had stopped routing everything to humans. Instead, they’d developed a sophisticated triage system where the AI handled routine inquiries while humans managed complex situations requiring empathy and judgment. Customer satisfaction scores had actually increased because humans weren’t burned out handling password resets and delivery confirmations.

Derek had become an unexpected AI advocate—not because he’d stopped being skeptical, but because he’d been given the time and resources to understand how to augment his expertise rather than be replaced by it. He’d discovered that AI routing, when combined with his institutional knowledge, could handle the 70% of shipments that were straightforward, leaving him to focus on the 30% that required human intuition.

The Human-Only chat still existed, but the tone had shifted. Now it was less about sabotage and more about troubleshooting—a place where humans could honestly discuss what AI did well, what it did poorly, and how to navigate the awkward space between.

This is what successful AI transformation actually looks like. Edmondson emphasizes this point: “If leaders want to unleash individual and collective talent, they must foster a psychologically safe climate where employees feel free to contribute ideas, share information, and report mistakes” (Strategy+Business, 2018). As she notes, “Psychological safety is not about being nice. It’s about giving candid feedback, openly admitting mistakes, and learning from each other” (The Agile Company, 2025).

Perhaps most tellingly, organizations that succeed take longer to show returns on their AI investments—18-24 months instead of the 6-12 months promised by most vendors—but their long-term outcomes are significantly better: higher retention of top talent, more sustainable productivity gains, and fewer catastrophic failures caused by poorly implemented systems.

Speed, it turns out, is overrated. Trust takes time.

Epilogue: The Meeting That Changed Everything

Three months after discovering the Human-Only chat, Margot sat in another boardroom—this time as a panelist at a regional technology conference. The topic was “AI Transformation Success Stories.”

A young product manager from a promising startup asked her the inevitable question: “What’s your advice for organizations just beginning their AI journey?”

Margot thought about Derek’s Phoenix shrimp. About Sarah’s exhausted face. About the seventeen thumbs-up reactions to a joke about job security. About all the things the glossy transformation roadmaps never mentioned.

“Assume your people are smarter than you are about how scared they should be,” she said. “Because they probably are. And then ask yourself: what would it take to make them feel secure enough to experiment with you instead of against you?”

“But what about speed to market?” the young product manager pressed. “Everyone says we need to move fast or get left behind.”

“Everyone’s wrong,” Margot said. “What gets you left behind isn’t moving slowly. It’s moving so fast that you lose your people in the process. Because no AI in the world can replace a team that trusts each other.”

It wasn’t the answer the audience wanted. Success stories are supposed to be about decisive action, bold vision, and triumphant results. Not about cold brew, difficult conversations, and the slow, messy work of rebuilding trust after breaking it.

But Margot had learned something more valuable than speed: that the hardest part of any technological transformation isn’t the technology. It’s remembering that the people using it are human, with mortgages and kids and fears and dreams and nineteen years of institutional knowledge that can’t be replicated by any model, no matter how sophisticated.

The mutiny hadn’t been a disaster. It had been a gift—a painful, necessary correction that had saved AeroStream from the trap that had caught so many other organizations: the belief that people are obstacles to be managed rather than partners to be trusted.

As she left the conference, Margot checked her phone. A message from Derek in the Humans + Machines chat: “AI just tried to send strawberries to Death Valley. Overrode it. Some things still need human judgment. 🍓💪”

Margot smiled. They were going to be okay.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2023). Rebalancing AI. Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/publications/fandd/issues/2023/12/rebalancing-ai-acemoglu-johnson

- Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019). The revolution need not be automated. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ai-automation-labor-productivity-by-daron-acemoglu-and-pascual-restrepo-2019-03

- AInvest. (2025, August 17). IgniteTech CEO lays off 80% workforce to drive AI transformation amid employee resistance. https://www.ainvest.com/news/ignitetech-ceo-lays-80-workforce-drive-ai-transformation-employee-resistance-2508/

- Bonnet, D. (2022). Digital transformation failure rates. Journal of Business Strategy, 43(2), 95-107.

- Briggs, J., & Kodnani, D. (2023, April 5). Generative AI could raise global GDP by 7 percent. Goldman Sachs. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent

- Cybersecurity Intelligence. (2024). Employee resistance to AI adoption. https://www.cybersecurityintelligence.com/blog/employee-resistance-to-ai-adoption-8641.html

- Deloitte. (2024). State of AI in the enterprise (6th ed.). Deloitte Insights. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/cognitive-technologies/state-of-ai-and-intelligent-automation-in-business-survey.html

- Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gartner. (2024). Gartner survey finds 70% of organizations report cultural resistance as primary barrier to AI adoption. Gartner Newsroom. https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom

- HR Dive. (2025, June 4). Nearly half of CEOs say employees are resistant or even hostile to AI. https://www.hrdive.com/news/employers-employees-resistant-hostile-to-AI/749730/

- LeanBlog. (2020, January 22). S1:E356 | Amy C. Edmondson on psychological safety and “The Fearless Organization.” https://www.leanblog.org/2020/01/s1e356-amy-c-edmondson-on-psychological-safety-and-the-fearless-organization/

- Libert, B., Beck, M., & Wind, Y. (2016). The network imperative: How to survive and grow in the age of digital business models. Harvard Business Review Press.

- MeltingSpot. (2025, November 26). Digital transformation failure rate 2025 – Why 70% of projects still fail. https://blog.meltingspot.io/why-digital-transformation-projects-fail/

- MIT Economics. (2024). Daron Acemoglu: What do we know about the economics of AI? https://economics.mit.edu/news/daron-acemoglu-what-do-we-know-about-economics-ai

- Oludapo, O., Ramesh, K., & Delen, D. (2024). Employee resistance in digital transformation: A systematic review. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(4), 892-916.

- Project Syndicate. (2019, March). The revolution need not be automated. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ai-automation-labor-productivity-by-daron-acemoglu-and-pascual-restrepo-2019-03

- Ramesh, K., & Delen, D. (2021). Digital transformation failure: A systematic review. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 63(5), 563-584.

- SHRM. (2024, November 14). When automation backfires: How rushed AI implementation can hurt employee engagement. https://www.shrm.org/enterprise-solutions/insights/when-automation-backfires–how-rushed-ai-implementation-can-hurt0

- Strategy+Business. (2018, November 14). How fearless organizations succeed. https://www.strategy-business.com/article/How-Fearless-Organizations-Succeed

- The Agile Company. (2025, May 27). Psychological safety is not about being nice: What leaders and coaches need to understand. https://theagilecompany.org/psychological-safety-is-not-about-being-nice/

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118-144.

- Vooban. (2024, November). Why your employees resist AI (and how to quickly overcome it)! https://vooban.com/en/articles/2024/11/why-your-employees-resist-ai-and-how-to-quickly-overcome-it

- World Economic Forum. (2023, February). Microsoft’s CEO on the future of work and the tech that will shape it. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/02/future-jobs-workplace-ai-microsoft/

- Yahoo Finance UK. (2024, January 15). Microsoft’s Satya Nadella reveals how AI will change jobs and companies. https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/microsoft-satya-nadella-ai-jobs-150331341.html

Additional Reading

- Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2023). Power and progress: Our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity. PublicAffairs.

- Daugherty, P. R., & Wilson, H. J. (2024). Radically human: How new technology is transforming business and shaping our future. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Edmondson, A. C., & Bransby, D. P. (2023). Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 55-78.

- Raisch, S., & Krakowski, S. (2021). Artificial intelligence and management: The automation-augmentation paradox. Academy of Management Review, 46(1), 192-210.

- Schwarzmüller, T., Brosi, P., Duman, D., & Welpe, I. M. (2023). How does the digital transformation affect organizations? Key themes of change in work design and leadership. Management Revue, 29(2), 114-138.

Additional Resources

- MIT Work of the Future Initiative – Comprehensive research on how technology is reshaping work and employment

https://workofthefuture.mit.edu/ - Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) – Research and reports on AI impact on society and organizations

https://hai.stanford.edu/ - Harvard Business School Digital Initiative – Case studies and research on digital transformation and organizational change

https://digital.hbs.edu/ - World Economic Forum Centre for the New Economy and Society – Reports on future of work and AI’s impact on employment

https://www.weforum.org/centre-for-the-new-economy-and-society/ - Brookings Institution – Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative – Policy research on AI and workforce development

https://www.brookings.edu/artificial-intelligence-and-emerging-technology-initiative/

Leave a Reply