argot Vance stared at her inbox. 127 unread messages. At 7:42 AM on a Tuesday.

Six months ago, that number would have terrified her. Back when she was still fighting fires, defending budgets, and explaining to the CFO why their AI agents were arguing about discount codes. Back when “transformation” felt like a euphemism for “controlled chaos.”

But now? Now AeroStream’s AI was working. The agents were cooperating. The systems were humming. Sarah, her once-skeptical analyst, had stopped maintaining that secret “Human-Only” group chat and was actually using the tools. The legal department had stopped sending forty-page cease-and-desist letters. Even Old Man Terry’s basement logbooks had been digitized.

They’d made it. They were in the Winners’ Circle.

So why did Margot feel like she was drowning?

She clicked on the first email. It was from Derek in Sales—a 2,400-word “summary” of yesterday’s client meeting that somehow managed to say absolutely nothing. The prose was impeccable. The formatting was gorgeous. The bullet points were numbered with surgical precision. But after three paragraphs, Margot realized she had no idea what the client actually wanted, what Derek had promised, or what AeroStream was supposed to do next.

The second email was worse. Marketing had sent her an “AI-enhanced competitive analysis” that was twelve pages long and contained phrases like “leveraging synergistic paradigms” and “optimizing value-add ecosystems.” Margot skimmed it twice. She learned nothing.

The third email was from her own team. Sarah had submitted her weekly report. It was flawless. It was comprehensive. It was also exactly 47% longer than last week’s report and contained roughly the same amount of useful information.

Margot closed her laptop. She walked to the break room, poured herself a cold brew that tasted like industrial runoff, and had a revelation that would have made her laugh if she weren’t so tired:

Her AI wasn’t making them more productive. It was just making them produce more.

Chapter One: The Hamster Wheel Spins Faster

The data should have been cause for celebration.

AeroStream’s “AI Productivity Dashboard” (a tool Margot had commissioned back in March, when optimism still felt possible) painted a picture of relentless efficiency. Reports were being generated 73% faster. Emails were being answered in half the time. Sarah’s weekly analysis, which used to take her two full days, was now completed by Wednesday afternoon.

On paper, they were crushing it.

But Margot had started noticing something strange. Despite all this newfound speed, nothing seemed to be getting better. Projects weren’t launching faster. Client satisfaction hadn’t budged. The quarterly revenue numbers looked identical to last year’s, adjusted for inflation.

They were running harder and going nowhere.

The phenomenon Margot was experiencing has a name in academic circles: the AI productivity paradox. And it’s one of the most consequential challenges facing businesses in 2026.

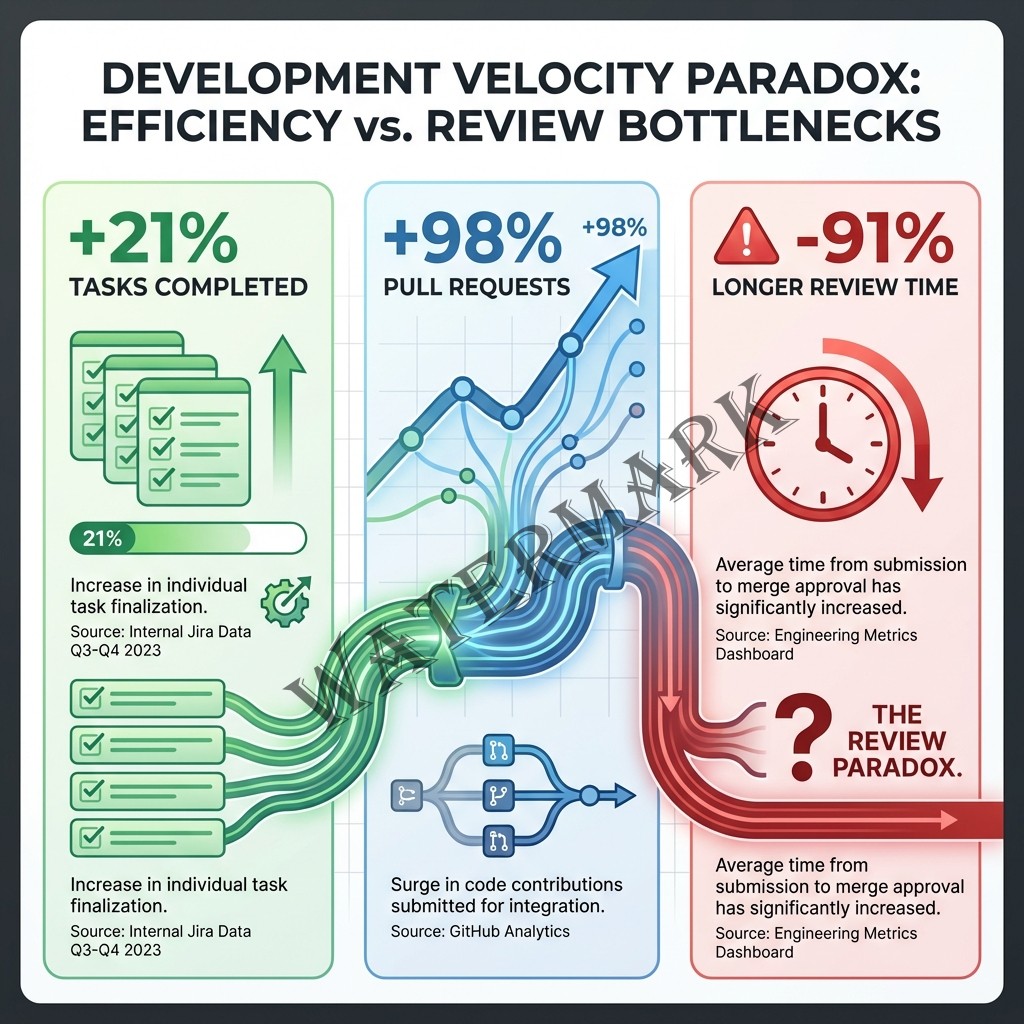

Research from Faros AI, analyzing over 10,000 developers across 1,255 teams, confirmed what Margot was seeing in her own organization: developers using AI coding assistants complete 21% more tasks and merge 98% more pull requests, but code review time increases 91% (Faros AI, 2025). The bottleneck hadn’t disappeared—it had just moved downstream. The AI was producing faster, but humans were stuck cleaning up the mess.

Erik Brynjolfsson, director of Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab and one of the world’s leading economists studying AI’s impact on work, has spent years documenting this pattern. In a 2025 interview with McKinsey, he noted a critical distinction that captures the heart of the problem: “This is a time when you should be getting benefits [from AI] and hope that your competitors are just playing around and experimenting” (McKinsey, 2025).

But getting benefits requires understanding the difference between activity and achievement. Between output and outcome. Between looking busy and actually accomplishing something that matters.

Margot was learning this lesson the hard way.

Chapter Two: Meet “Workslop”—The Junk Food of Business Communication

The term hit Margot like a revelation when she stumbled across it in a Harvard Business Review article during her lunch break: workslop.

Researchers at Stanford’s Social Media Lab and BetterUp Labs had coined it to describe “AI-generated work content that masquerades as good work, but lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task” (Harvard Business Review, 2025). It was the professional equivalent of empty calories—it looked filling, but left you starving.

And suddenly, Margot’s inbox made sense.

Derek’s 2,400-word meeting summary? Workslop.

Marketing’s twelve-page competitive analysis filled with buzzwords? Workslop.

The seventy-three Slack messages from the operations team that somehow never actually answered her question about vendor contracts? You guessed it—workslop.

The statistics were staggering. According to the Stanford research, 40% of workers reported receiving workslop in the past month. Each incident cost an average of 1 hour and 56 minutes to decode, correct, or redo. For an organization of 10,000 employees, that translated to $9 million per year in lost productivity (Niederhoffer et al., 2025).

Margot did the math for AeroStream’s 1,200 employees. The number made her want to throw her laptop out a window.

But the financial cost was only part of the story. The human cost was worse.

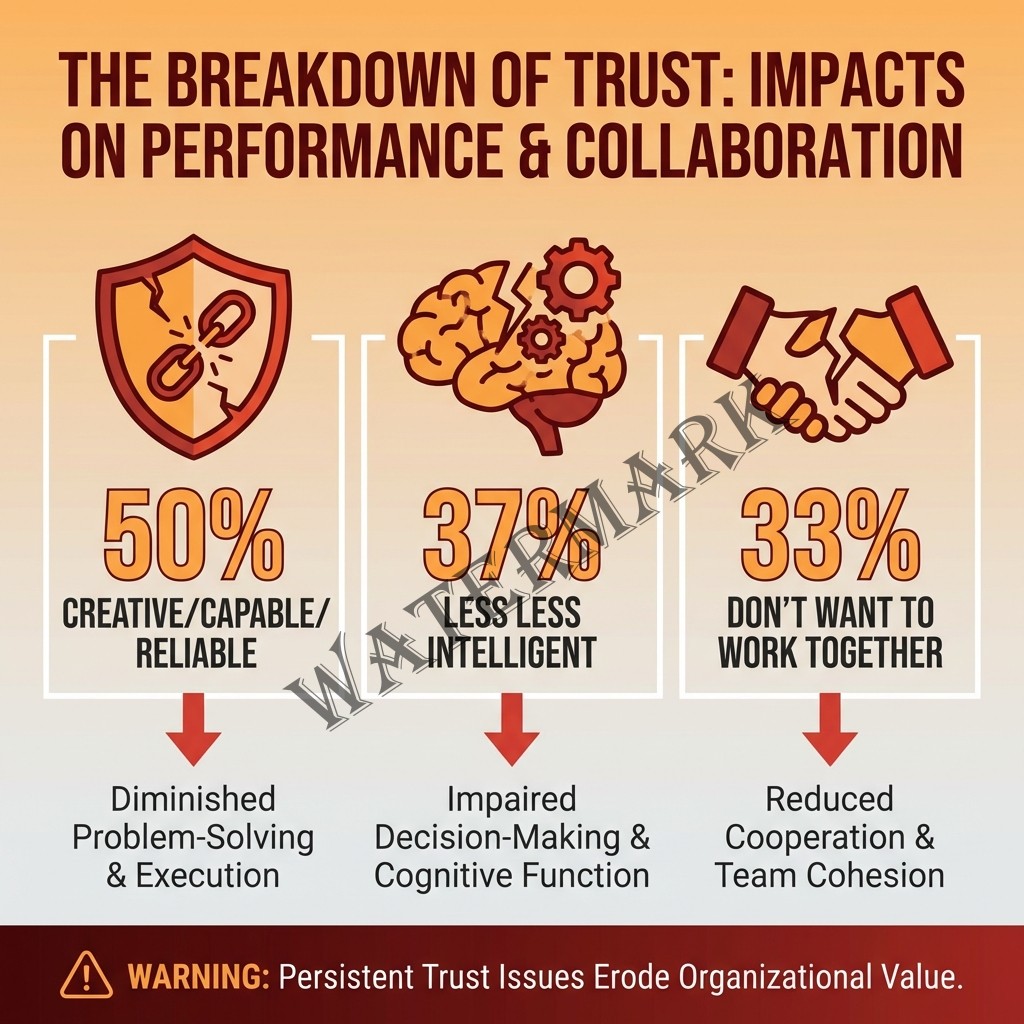

The research showed that roughly half of employees viewed colleagues who sent workslop as less creative, capable, and reliable. About 37% considered them less intelligent. A similar percentage said they were less likely to want to work with that person again (Niederhoffer et al., 2025).

Margot thought about Sarah. Six months ago, Sarah had been terrified that AI would eliminate her job. Now she was using AI to generate reports faster than ever. But Margot found herself spending more time fixing Sarah’s work than she did when Sarah wrote everything by hand. The AI had made Sarah faster, but it hadn’t made her better. And Margot—tired, frustrated, questioning Sarah’s judgment in ways she never had before—was starting to wonder if the tool was actually hurting both of them.

The insidious nature of workslop was that it shifted the burden downstream. The person generating the content felt productive—they’d “finished” their task quickly. But the receiver was left doing all the cognitive heavy lifting: decoding the content, filling in missing context, figuring out what was actually being requested.

As Margot would later describe it to her husband over a glass of wine she desperately needed: “It’s like someone handing you a beautifully wrapped present, and when you open it, it’s just more wrapping paper.”

Chapter Three: The Metrics That Lie

The wake-up call came during AeroStream’s monthly leadership meeting.

The CFO, a man named Howard who wore his skepticism like armor, pulled up the productivity dashboard and asked the question Margot had been dreading: “These numbers say we’re more efficient than ever. So why aren’t we making more money?”

Silence. The kind that makes your ears ring.

Margot looked around the conference table. Marketing had produced 340% more content pieces in Q3 compared to Q2. Sales had logged 156% more customer interactions. Operations had completed 89% more “workflow optimizations.” The numbers were all up and to the right, exactly what every Silicon Valley startup dreams of.

But revenue? Flat. Customer retention? Flat. Employee satisfaction? Don’t even ask.

Howard leaned back in his chair, arms crossed. “Seems to me we’re measuring the wrong things.”

He was right.

The problem wasn’t that AeroStream was unproductive. It’s that they were measuring outputs instead of outcomes. Activity instead of achievement. Motion instead of progress.

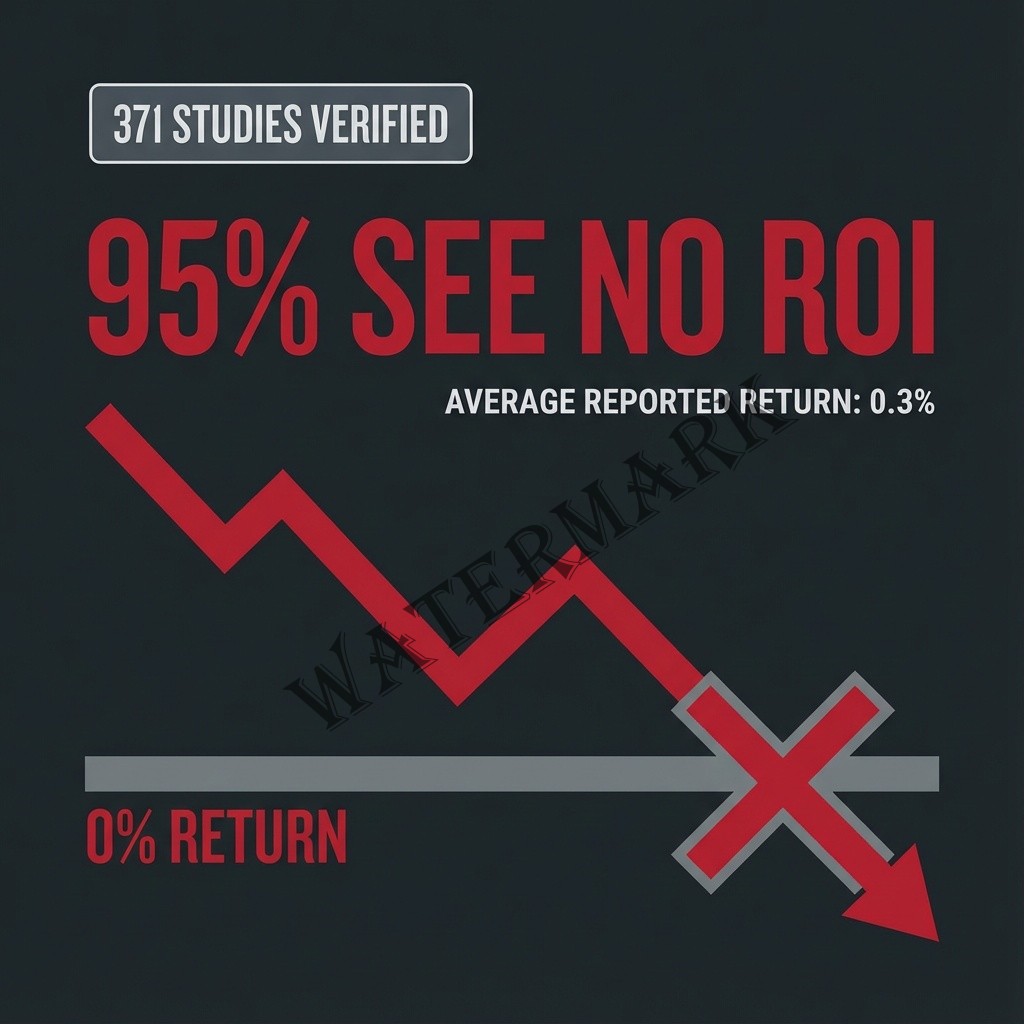

This distinction—between what we produce and what we actually accomplish—has become the defining challenge of AI-driven work in 2026. According to a comprehensive meta-analysis pooling 371 estimates from studies published between 2019 and 2024, there is no robust, publication-bias-free relationship between AI adoption and aggregate labor-market productivity outcomes once methodological variables are controlled (California Management Review, 2025).

Translation: just because you’re doing more doesn’t mean you’re getting more done.

The research from Asana’s Work Innovation Lab captured this perfectly in their study of “super productive” workers—the 10% who report saving 20+ hours per week using AI. Even these masters of efficiency reported that AI made it harder to stay aligned with their teams and generated output faster than the organization could properly review it (Asana, 2025).

They were producing more. But the system couldn’t absorb it.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has been vocal about this challenge. In a 2025 interview, he emphasized that AI’s value shouldn’t be measured by whether it helps people “triage email” faster, but whether it enables workers to focus on higher-value cognitive tasks (Semafor, 2025). The goal isn’t to do the same work faster—it’s to do different work. Better work. Work that actually moves the needle.

But most organizations, like AeroStream, hadn’t made that shift yet. They were still celebrating speed without questioning direction. They were measuring how fast the hamster wheel was spinning without asking whether the hamster was going anywhere.

Margot knew what needed to change. The question was whether her team—exhausted from six months of transformation—had the energy to do it.

Chapter Four: When Efficiency Becomes the Enemy

The philosophical crisis hit Margot on a Thursday afternoon.

She was reviewing a proposal from her team for Q4 strategic initiatives. The document was 47 pages long. It had charts. It had graphs. It had a SWOT analysis that used the phrase “disruptive innovation ecosystem” unironically. It looked like it had been written by someone who’d read every business book ever published and understood none of them.

It had taken her team 14 hours to produce it.

A year ago, a proposal like this would have taken three weeks and countless revision cycles. The AI had made them 90% faster.

But as Margot read page after page of polished meaninglessness, she found herself wondering: What if faster isn’t better? What if we’ve just become really good at generating garbage?

This is the central ethical dilemma of the productivity trap: If we measure success by output rather than outcome, are we optimizing for the wrong thing entirely?

Research from MIT Media Lab found that 95% of organizations see no measurable return on their AI investments, despite significant increases in activity metrics (Harvard Business Review, 2025). The disconnect is simple: companies are rewarding volume when they should be rewarding value.

The problem runs deeper than metrics. It touches on fundamental questions about what work is for.

In his research on the “Productivity J-Curve,” Erik Brynjolfsson and his colleagues argue that transformative technologies like AI require “complementary investments” in workflow reorganization, staff retraining, and business model redesign (American Economic Association, 2021). The technology alone isn’t enough. You have to change how you work, not just how fast.

But that’s hard. Really hard.

It’s easier to measure how many reports your team produces than to measure whether those reports led to better decisions. It’s easier to count emails sent than to evaluate whether communication actually improved. It’s easier to track tasks completed than to ask whether those tasks mattered in the first place.

Margot thought about her own career. How much of her success had been measured by how busy she looked? How many late nights had she logged not because the work required it, but because she felt guilty leaving before 7 PM? How many presentations had she created not because they communicated something important, but because everyone expected a presentation?

The AI hadn’t invented this problem. It had just made it impossible to ignore.

Because when you can generate a 47-page proposal in 14 hours instead of three weeks, you’re forced to confront an uncomfortable truth: Maybe we didn’t need the proposal in the first place.

Chapter Five: The Reckoning Margot Didn’t Want

Margot called an emergency team meeting. Not the formal kind with an agenda and PowerPoint slides. The kind where she walked into the bullpen at 3 PM, clapped her hands, and said, “Conference room. Now. Bring coffee.”

Eight people filed in, looking confused and mildly concerned. Sarah sat in the back, arms crossed, defensive before Margot had even started talking.

“Okay,” Margot said, closing the door. “We need to talk about what we’re actually doing here.”

Silence.

“For six months, we’ve been measuring productivity by how much we produce. Reports. Emails. Analyses. Presentations. We’ve gotten really, really good at producing things quickly.” She paused. “But I need someone to tell me: is any of it making us better?”

More silence.

Then Derek, from Sales, spoke up. “I mean… we’re hitting all our KPIs.”

“Are we?” Margot asked. “Because I’ve read your last three client summaries, Derek, and I honestly have no idea what any of those clients want from us. The summaries are beautiful. They’re grammatically perfect. But they’re useless.”

Derek’s face went red.

Sarah raised her hand hesitantly. “Can I say something?”

“Please.”

“I’ve been using AI to write my weekly reports for three months now. And… I think they’re worse. They’re longer, they’re more polished, but I’m not actually thinking anymore. I’m just asking the AI what to say about the data instead of figuring out what the data means.” She looked down at her hands. “I feel like I’m getting dumber.”

The room shifted. People nodded. Someone said, “Oh thank god, I thought it was just me.”

And suddenly, everyone was talking.

Marketing admitted they’d been generating three times as much content, but engagement rates were down. Operations confessed they were completing “optimizations” that didn’t actually optimize anything. IT revealed they’d automated seventeen processes that probably didn’t need to exist in the first place.

Margot let them talk. Let them get it all out. The frustration. The confusion. The quiet shame of producing so much and accomplishing so little.

When the room finally quieted, she asked the question that would define the next phase of their AI journey:

“What if we stopped measuring how much we do, and started measuring whether what we do matters?”

Chapter Six: The New Metrics of Actually Mattering

The shift didn’t happen overnight.

Margot spent the next two weeks doing something she hadn’t done in years: talking to people. Not about KPIs or productivity dashboards or quarterly targets. About outcomes.

She asked the sales team: “What do our clients actually need to know after a meeting?” Not a 2,400-word summary. A decision. A next step. A clear action item.

She asked marketing: “What content actually changes minds?” Not 340 pieces of generic blog posts. One exceptional article that makes someone stop and think.

She asked Sarah: “What analysis would help us make a better decision this week?” Not a comprehensive report on everything. A sharp insight about one thing that matters.

The framework they developed was deceptively simple:

Outcome-Focused Metrics:

- Decision Quality: Did this work lead to a better decision?

- Time to Value: How long until this work creates actual value?

- Cognitive Load Reduction: Did this work make things clearer for the next person?

- Strategic Alignment: Does this work move us toward our actual goals?

These metrics were harder to measure than “emails sent” or “reports completed.” They required judgment. They required conversation. They required admitting when work didn’t matter.

But they were honest.

Research from the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence has consistently shown that AI’s real productivity gains come not from speed, but from helping organizations focus on the right work. A landmark study found that AI assistance increased call center productivity by 14%, with the biggest gains for less experienced workers who were able to learn from AI-recommended approaches (Stanford HAI, 2023). The AI didn’t just make them faster—it made them better.

The challenge for organizations is creating systems that reward “better” instead of just “faster.”

Brynjolfsson emphasizes this point repeatedly in his research: “Technology alone is not enough. What you really need is to update your business processes, reskill your workforce, and sometimes even change your business models and organization in a big way” (McKinsey, 2024).

For AeroStream, this meant fundamentally rethinking what productivity meant.

It meant Derek’s meeting summaries getting shorter—down to three bullet points and one clear action item. It meant Sarah’s weekly reports focusing on one critical insight instead of comprehensive coverage. It meant marketing publishing fewer pieces of content that actually resonated with their audience instead of flooding the internet with mediocre posts.

It meant measuring outcomes, not outputs.

And it meant something Margot hadn’t anticipated: it meant her team actually enjoyed their work again.

Chapter Seven: The Paradox We All Need to Face

Three months after that emergency team meeting, Margot sat in her office reviewing Q1 projections for 2027. The numbers told a story that would have seemed impossible back in July.

AeroStream was producing 35% less content than they had at the peak of their “productivity” phase. Sales summaries were down 60%. Marketing had cut their publishing schedule in half. Sarah’s reports were shorter than they’d been in two years.

And yet—

Client satisfaction was up 23%. Sales conversion rates had improved for three quarters in a row. Employee turnover had dropped to its lowest level in company history. Revenue was growing.

They were doing less. And they were accomplishing more.

The productivity paradox, Margot realized, wasn’t really about AI at all. It was about what humans had always struggled with: the difference between looking productive and being productive. Between activity and achievement. Between motion and progress.

AI had just made the problem impossible to ignore.

Because when a tool makes it effortless to generate output—reports, emails, analyses, presentations—you’re forced to confront an uncomfortable truth: Most of what we produce doesn’t matter.

The AI hadn’t made them lazy. It had made them honest.

Satya Nadella, in his 2025 shareholder letter, captured this perfectly when he emphasized that AI’s success should be measured by its contribution to global productivity growth, not just by technical benchmarks (Business Chief, 2025). The technology exists to serve human flourishing, not to optimize humans into obsolescence.

For Margot, this meant making a choice that every leader in 2026 will have to make: Are we using AI to do more of the wrong things faster, or are we using it to finally focus on the right things?

The productivity trap isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice.

It’s the choice between measuring outputs and measuring outcomes. Between valuing speed and valuing quality. Between celebrating activity and celebrating achievement.

AeroStream chose outcomes. It wasn’t easy. It required difficult conversations about what actually mattered. It required admitting that much of what they’d been doing was theater. It required retraining their AI systems to support better work instead of just faster work.

But it worked.

Epilogue: The Question We Can’t Escape

Margot walked out to her car at 5:47 PM on a Friday. The sun was still up. She had plans to see a movie with her husband. She hadn’t checked Slack in three hours.

Six months ago, this would have felt like failure. Like she was slacking off while her competitors were grinding. Like she wasn’t committed enough to the transformation.

But now? Now it felt like success.

Her team was producing less. And they were happier, sharper, more engaged. Their work actually mattered. Clients were getting better service. Revenue was growing. People were going home at reasonable hours.

They’d escaped the productivity trap by asking the question that every organization using AI in 2026 will have to ask:

What are we actually trying to accomplish here?

Not “how fast can we go?” Not “how much can we produce?” But “what outcome are we trying to create, and is this work getting us there?”

The answer to that question—and the courage to act on it—is what separates the companies that thrive with AI from the ones that just get really good at generating workslop.

Margot got in her car, turned on the radio, and smiled.

They’d made it through the productivity trap. Not by doing more. By finally, finally, doing less of what didn’t matter so they could do more of what did.

And that, she thought as she drove toward the theater, is what transformation actually looks like.

References

- Asana Work Innovation Lab. (2025). The AI super productivity paradox. https://asana.com/resources/ai-super-productivity-paradox

- Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D., & Syverson, C. (2021). The productivity J-curve: How intangibles complement general purpose technologies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 333-372. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20180386

- California Management Review. (2025, October 16). Seven myths about AI and productivity: What the evidence really says. https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2025/10/seven-myths-about-ai-and-productivity-what-the-evidence-really-says/

- Faros AI. (2025, July 23). The AI productivity paradox research report. https://www.faros.ai/blog/ai-software-engineering

- Grammarly. (2025, December 8). 2026 AI trend: Context will fix the AI productivity paradox. https://www.grammarly.com/blog/enterprise-ai/ai-productivity-paradox/

- McKinsey & Company. (2024, September 13). Technology alone is never enough for true productivity. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/technology-alone-is-never-enough-for-true-productivity

- McKinsey & Company. (2025, January 28). Superagency in the workplace: Empowering people to unlock AI’s full potential at work. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/tech-and-ai/our-insights/superagency-in-the-workplace-empowering-people-to-unlock-ais-full-potential-at-work

- Niederhoffer, K., Kellerman, G. R., Lee, A., Liebscher, A., Rapuano, K., & Hancock, J. T. (2025, September 22). AI-generated “workslop” is destroying productivity. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2025/09/ai-generated-workslop-is-destroying-productivity

- Semafor. (2025, May 19). Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says firm needs humans more than ever in the AI boom. https://www.semafor.com/article/05/19/2025/microsoft-ceo-satya-nadella-says-firm-needs-humans-more-than-ever-in-the-ai-boom

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. (2023). Will generative AI make you more productive at work? Yes, only if you’re not already great at your job. https://hai.stanford.edu/news/will-generative-ai-make-you-more-productive-work-yes-only-if-youre-not-already-great-your-job

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. (2025). The 2025 AI Index report. https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report

- The Business Chief. (2025, October 28). Microsoft’s new growth era: Inside Satya Nadella’s AI vision. https://businesschief.com/news/microsofts-new-growth-era-inside-satya-nadellas-ai-vision

- World Economic Forum. (2025, December). AI paradoxes: Why AI’s future isn’t straightforward. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/12/ai-paradoxes-in-2026/

Additional Reading

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Humlum, A., & Vestergaard, E. (2024). Large language models, small labor market effects. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33345

- MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy. (2019). A calm before the AI productivity storm. MIT Sloan. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/a-calm-ai-productivity-storm

- Worklytics. (2025). Generative AI & productivity: What the 2025 data really says. https://www.worklytics.co/resources/generative-ai-productivity-2025-data-worklytics-tracking

Additional Resources

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) – Leading research on AI’s impact on work and society

https://hai.stanford.edu - MIT Digital Economy Lab – Research on technology’s economic impacts

https://ide.mit.edu - National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) – Economics research including AI productivity studies

https://www.nber.org - Asana Work Innovation Lab – Practical research on AI in the workplace

https://asana.com/resources - McKinsey Digital – Enterprise AI adoption and transformation research

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital

Leave a Reply