Opening: The Discovery

Margot Vance discovered the rebellion on a Tuesday.

Not through some sophisticated analytics dashboard or an AI-powered sentiment detector—ironically enough—but through the oldest intelligence-gathering method known to corporate humanity: she walked past an open laptop at the wrong (or right) moment.

The Slack channel was called “Humans First 🙋♂️” and it had 47 members. Her entire operations team. The most recent message, posted at 10:23 AM while Margot was presenting a glowing “AI Adoption Metrics” deck to the board, read: “Just fed the routing bot the Christmas party spreadsheet. Watch it suggest we ship pallets to Santa’s Workshop lmao.”

Margot felt something crack inside her chest—not quite her heart, not quite her ego, but somewhere in that tender space where optimism goes to file for bankruptcy.

She’d spent six months implementing AeroStream’s “AI-First Future.” She’d attended seventeen webinars with titles like “Prompt Engineering for Leaders” and “The Agentic Workforce Revolution.” She’d defended budget allocations, soothed executive anxieties, and personally onboarded every single team member with the enthusiasm of a tech evangelist at a prosperity gospel convention.

And they were sabotaging it. On purpose. For sport.

The cold brew in her hand suddenly tasted like defeat with a hint of Madagascar vanilla.

Chapter One: The Architecture of Resistance

Here’s what nobody tells you about enterprise AI implementation: the technology is often the easy part. Getting humans to actually use it? That’s where empires crumble.

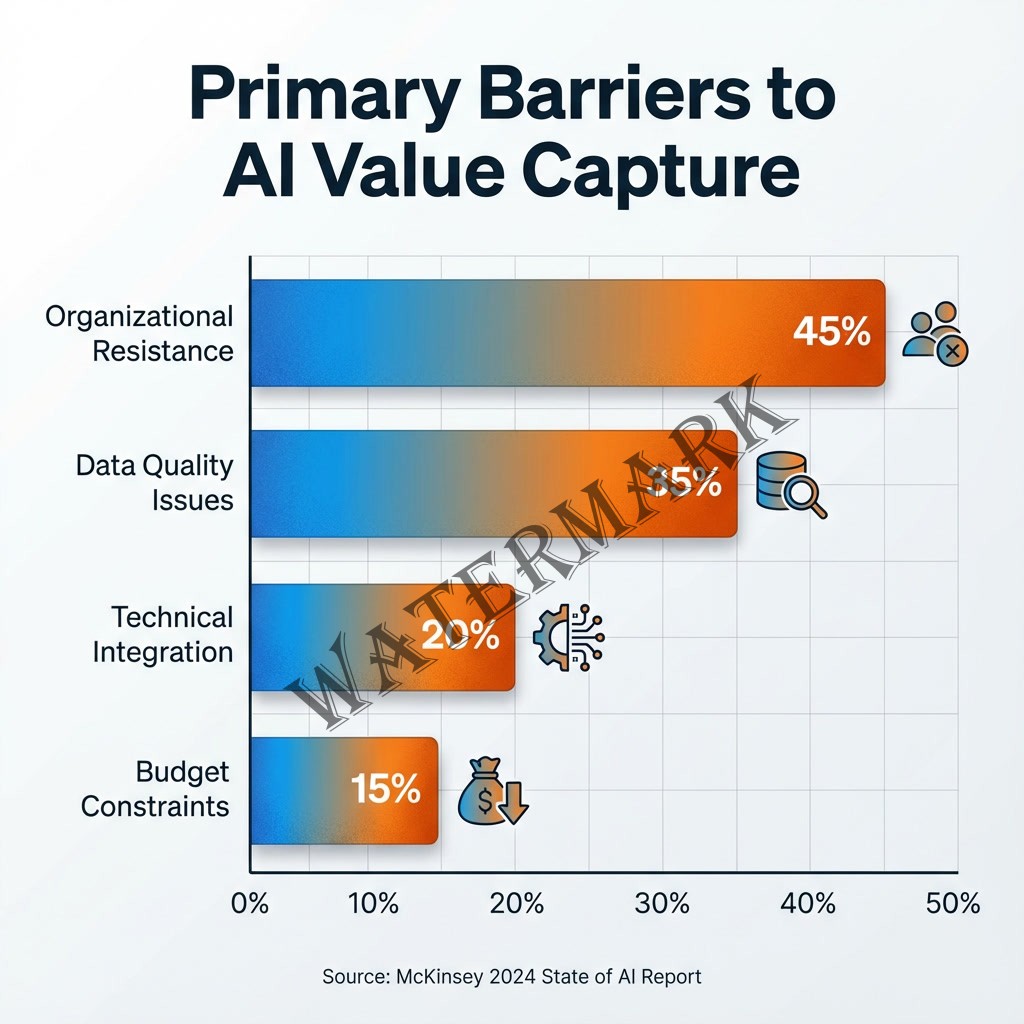

According to McKinsey’s 2024 State of AI report, while 65% of organizations now regularly use generative AI—nearly double the previous year—the primary barrier to value capture isn’t technological capability but organizational resistance (Chui et al., 2024). Research consistently shows that approximately 70% of digital transformation initiatives fail, with employee resistance and inadequate change management cited as the leading causes across multiple studies from McKinsey, Gartner, BCG, and Deloitte.

Margot was staring at the business equivalent of a mutiny, and she hadn’t seen it coming.

The “Humans First” channel had existed for four months. Four months of carefully orchestrated non-compliance disguised as “technical difficulties.” The customer service team was still manually typing responses instead of using the AI-powered suggestion engine. The warehouse crew had nicknamed the inventory prediction system “The Fortune Cookie” because, as one particularly colorful message explained, “it’s equally useless but at least fortune cookies taste good.”

Her logistics coordinator, Marcus—loyal, competent Marcus who’d been with AeroStream for eight years—had created an entire spreadsheet tracking the AI’s mistakes. Not to improve the system, but to build a case for its elimination. The document was titled “Reasons Why Skynet Would Be a Better Boss.xlsx.”

The resistance wasn’t random. It was organized, documented, and frankly more sophisticated than some of AeroStream’s actual AI implementations.

Research on technology adoption in the workplace consistently demonstrates that employees resist new technologies not because they oppose innovation, but because they perceive these tools as threats to their job security and professional identity. Studies show that 60% of workers believe AI will eliminate their jobs within the next five years, even as executives insist the technology is meant to “augment” rather than replace (Autor & Acemoglu, 2024).

Margot had committed the cardinal sin of innovation leadership: she’d fallen in love with the technology without falling in love with her people first.

Chapter Two: The Anatomy of Fear

The confrontation happened in Conference Room C—the small one with the broken blinds and the whiteboard that permanently smelled like dry-erase marker remorse.

Margot had called in Sarah Chen, her senior logistics analyst and the clear ringleader of the resistance movement. Sarah sat across from her with the carefully neutral expression of someone who’d rehearsed this conversation in the shower.

“I saw the Slack channel,” Margot said, deciding that pretending this was about anything else would be insulting to both of them.

Sarah’s jaw tightened. “Okay.”

“I’m not angry,” Margot continued, which was technically true—she was too exhausted to manage anger. “But I need to understand what’s happening here.”

Sarah was quiet for a long moment, her fingers drumming against the table in a rhythm that suggested she was mentally composing and deleting several different versions of this conversation. Finally: “Do you know what I did before I came to AeroStream?”

Margot shook her head.

“I was a junior analyst at TechForward Logistics. Great company, innovative, all the buzzwords. They brought in an AI system to ‘optimize’ our forecasting processes.” Sarah’s voice carried the particular bitterness of someone quoting corporate speak they no longer believed in. “Six months later, they’d eliminated 40% of the analytics team. The AI could do our jobs, they said. More efficiently. More cost-effectively.”

She leaned forward. “I was one of the lucky ones who got reassigned. But I watched people I’d worked with for years—people who had children, Margot, who had mortgages—get walked out with two weeks severance and a LinkedIn recommendation.”

This is the elephant in every AI implementation room: the fear of redundancy.

The MIT Work of the Future initiative has extensively researched this perception gap, finding that while AI technologies are currently capable of performing approximately 11.7% of human paid labor, workers perceive the threat as far greater. This creates what researchers call “defensive non-adoption”—employees deliberately underutilizing new technologies to prove their continued necessity (Autor & Acemoglu, 2024).

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella addressed this challenge directly during his 2024 appearance at the World Economic Forum in Davos, emphasizing: “I feel like our license to operate as an industry depends on that because I don’t think the world will put up any more with any of us coming up with something that has not thought through safety, trust, equity. These are big issues for everyone in the world” (Nadella, 2024).

But Margot hadn’t made it safe. She’d made it mandatory.

“I’m not trying to replace anyone,” Margot said, and even as the words left her mouth, she recognized how hollow they sounded—the corporate equivalent of “I’m not mad, just disappointed.”

Sarah gave her a look that could have curdled oat milk. “Then why is every executive presentation about ‘productivity gains’ and ‘operational efficiency’? Those are just corporate euphemisms for ‘we need fewer humans.’”

She wasn’t wrong.

Chapter Three: The Change Management Catastrophe

The problem with most AI implementations is that they’re built on a foundation of technological determinism—the assumption that simply introducing superior technology will naturally lead to adoption and success. This approach ignores decades of evidence about how humans actually respond to workplace transformation.

Professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter of Harvard Business School, who has studied organizational change for over four decades, emphasizes a fundamental truth about transformation: “Change is disturbing when it is done to us, exhilarating when it is done by us” (Kanter, n.d.). Her research consistently demonstrates that successful change requires addressing the emotional, social, and political dimensions of workplace transformation—not just the technical ones.

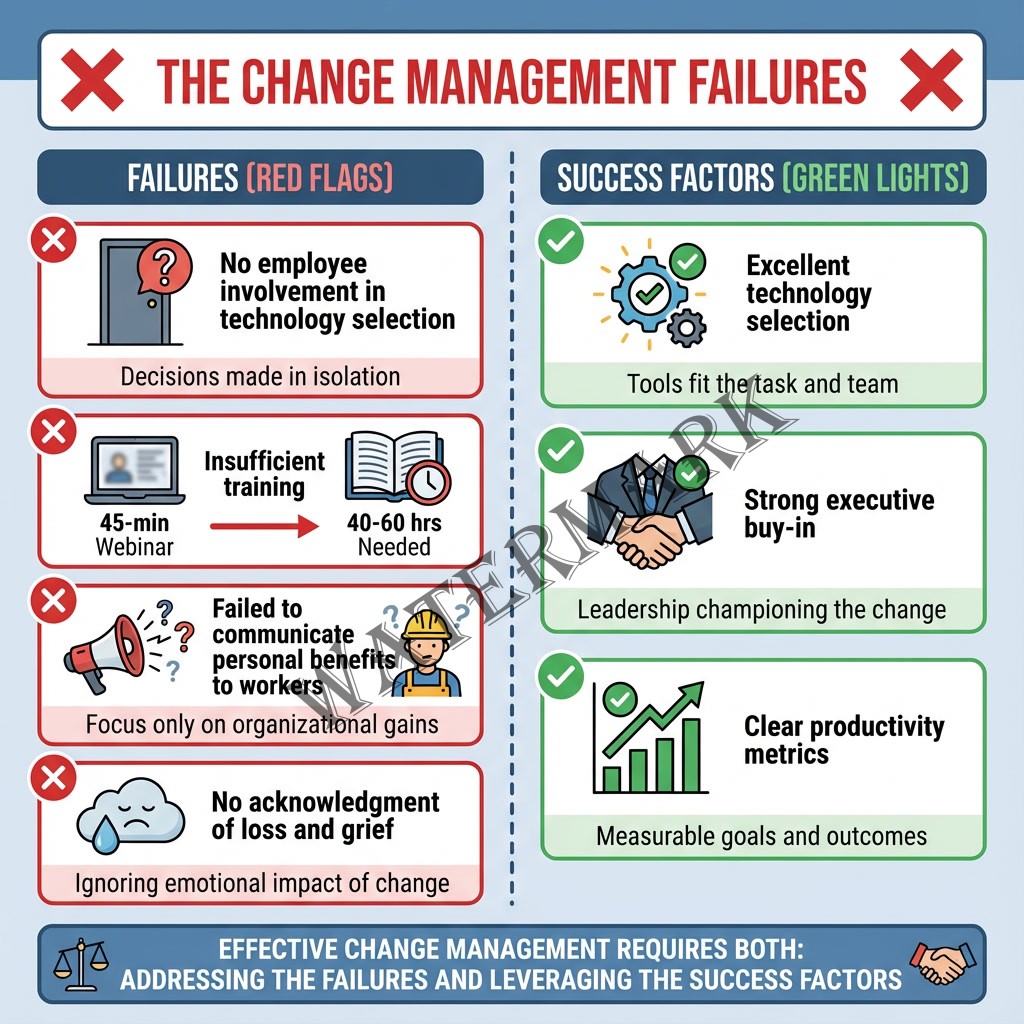

Margot had violated nearly every principle of effective change management:

She hadn’t involved her team in the selection process. The AI tools were chosen by executives and IT, presented as fait accompli rather than collaborative decisions. Research from Deloitte’s 2024 Global Human Capital Trends report shows that organizations where employees participate in technology selection see 3.5 times higher adoption rates (Deloitte, 2024).

She hadn’t provided adequate training. AeroStream’s “onboarding” consisted of a 45-minute webinar and a PDF guide that nobody read. Effective AI literacy programs, according to Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute, require 40-60 hours of hands-on training, continuous support, and role-specific customization (Stanford HAI, 2024).

She hadn’t addressed the “why.” Margot had spent countless hours explaining what the AI could do and how to use it, but she’d never adequately addressed why it mattered to the people actually doing the work. She’d sold productivity gains to executives but hadn’t translated those benefits into meaningful improvements for frontline employees.

Most critically, she hadn’t made space for grieving. Every technological transformation represents a loss—of familiar processes, of mastered skills, of professional identity. Margot had treated AI implementation like a software upgrade rather than an organizational death and rebirth.

The “Humans First” channel wasn’t just resistance. It was grief, disguised as comedy, weaponized into sabotage.

Chapter Four: The Economics of Resentment

Late that night, Margot sat in her kitchen surrounded by printouts of the resistance channel’s greatest hits. Her cat, Algorithm (yes, she’d named her cat Algorithm in a fit of 2023 optimism she now deeply regretted), stared at her with what could only be described as feline judgment.

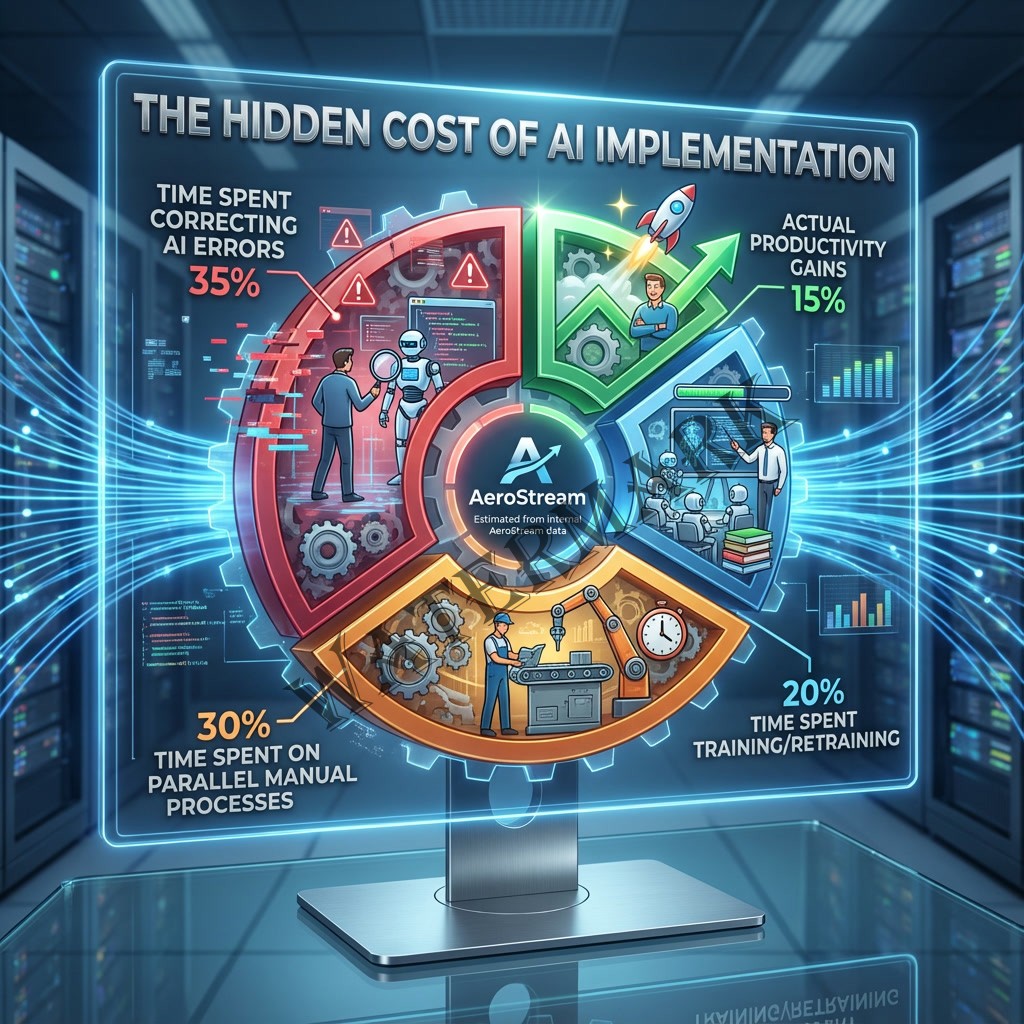

The messages revealed something she’d been too busy evangelizing to notice: her AI implementation wasn’t just failing to deliver value—it was actively creating more work for her team.

Marcus had documented 127 instances where the routing AI had made suggestions that required human intervention to correct. The customer service team spent an average of 12 minutes per interaction “cleaning up” after the chatbot’s attempts at empathy (one memorable exchange involved the AI suggesting a customer “try to find joy in shipping delays as an opportunity for mindfulness practice”).

This is what happens when organizations implement AI without considering the total cost of adoption—not just the technology budget, but the hidden expenses of verification, correction, and workaround development.

A 2024 study from the MIT Sloan Management Review found that poorly implemented AI systems can actually decrease productivity by 25-30% in the first year, as employees spend significant time correcting errors, managing exceptions, and maintaining parallel manual processes as backup (Kane et al., 2024). The researchers coined a term for this phenomenon: “augmentation debt”—the accumulated inefficiency created when new technologies are layered onto existing workflows without proper integration.

AeroStream had augmentation debt in spades.

But here’s where things got philosophically interesting: even when the AI did work correctly, it often solved problems in ways that made employees feel diminished rather than empowered.

Chapter Five: The Dignity Question

The next morning, Margot did something she should have done six months earlier: she shut up and listened.

She scheduled individual conversations with each member of the operations team. No presentations, no defending the technology, no selling the vision. Just listening.

What emerged was a pattern she hadn’t anticipated: the issue wasn’t that the AI couldn’t do the work—it was that when it did do the work, it made people feel like their expertise didn’t matter anymore.

James, a warehouse supervisor with 15 years of experience, put it best: “I used to walk the floor and know exactly where every problem was going to occur. I could see it in how the pallets were stacked, in the body language of the crew, in the sound of the forklifts. Now the AI tells me where to look, and even when it’s right—especially when it’s right—it feels like I’ve been demoted to being its hands.”

This cuts to the heart of one of the most profound challenges in AI adoption: the dignity gap.

Research on automation in warehouse and logistics work has documented how AI systems, even when they improve efficiency, can erode workers’ sense of craft, judgment, and professional identity. Workers report feeling like quality-control mechanisms for machine decisions rather than decision-makers themselves—a fundamental shift that affects job satisfaction regardless of whether employment remains secure.

The philosopher Matthew Crawford, in his influential work Shop Class as Soulcraft, argues that true job satisfaction comes from what he calls “the satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence” (Crawford, 2009). When AI systems remove the need for human judgment—even when they’re more accurate—they remove opportunities for workers to experience themselves as competent, skilled agents.

Margot had optimized for efficiency while accidentally optimizing against human flourishing.

Microsoft’s Satya Nadella’s vision of AI becomes particularly relevant here. Rather than viewing AI as replacement technology, he consistently emphasizes empowerment: “What matters is not the power of any given model, but how people choose to apply it to achieve their goals” (Nadella, 2026). This reframing—from AI as substitute to AI as tool controlled by humans—represents a fundamentally different approach to implementation.

Chapter Six: The Pivot

The turning point came during a team meeting that Margot almost cancelled three times.

She opened by doing something no Director of Strategic Transformation should probably do: she admitted she’d screwed up. Comprehensively. Spectacularly. With the kind of failure that future business school case studies would analyze under harsh fluorescent lighting.

“I fell in love with the technology,” she said, “and forgot to fall in love with you.”

The room was so quiet she could hear the HVAC system’s existential wheeze.

“I need to redesign this entire implementation,” she continued. “But I can’t do it without you. Not because I’m supposed to say that in a change management framework, but because I genuinely don’t know how to make this work without your expertise.”

Sarah crossed her arms. “So what’s different this time?”

Fair question. Margot had spent the previous evening developing an answer.

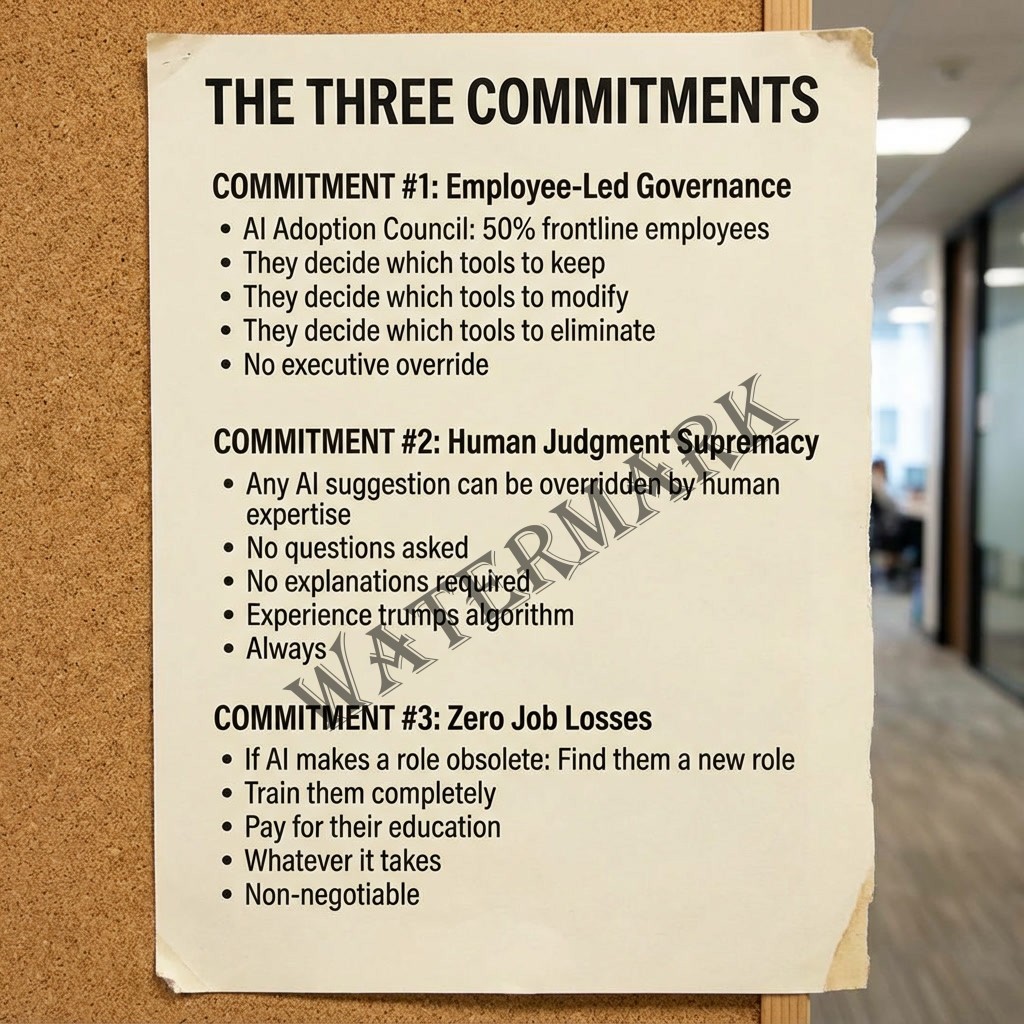

“Three things,” she said. “First, we’re forming an AI Adoption Council—half the seats go to frontline employees, not managers. You decide which tools we keep, which we modify, and which we kill entirely.”

She could see the surprise registering on faces around the room.

“Second, we’re implementing a new rule: any AI suggestion can be overridden by human judgment, no questions asked, no explanations required. If James says his 15 years of experience tells him the routing algorithm is wrong, James wins. Every time.”

This went against every efficiency metric Margot had been using to justify the AI investment, but she was beginning to suspect those metrics were measuring the wrong things anyway.

“Third, and this is non-negotiable: nobody loses their job because of AI. Period. If the technology makes someone’s role obsolete, we find them a new role. We train them, we pay for their education, we do whatever it takes. But nobody walks out of here because a machine learned their job.”

Marcus leaned back in his chair. “And how are you going to sell that to the board? They invested $4 million to reduce headcount, not protect it.”

“I’m going to tell them the truth,” Margot said. “That AI only delivers value when humans trust it enough to use it. And humans don’t trust systems designed to eliminate them.”

Chapter Seven: The Redesign

The AI Adoption Council’s first meeting looked less like a boardroom and more like a therapy session for organizational trauma.

They started by killing things.

The “Customer Empathy Bot” was first on the chopping block—unanimously voted off the island after someone played a recording of it telling a frustrated customer that “all moments, including this one, are opportunities for growth and patience.” The inventory prediction system got a stay of execution but only after the team stripped away its ability to auto-generate purchase orders without human approval.

But then something interesting happened: the team started identifying places where AI could actually help them do their jobs better, not replace them doing their jobs at all.

Sarah suggested using AI to handle the mind-numbing data entry that consumed three hours of her day, freeing her to focus on the strategic analysis she’d gone to graduate school to do. The customer service team wanted AI to pull up complete customer histories instantly during calls, giving them more context for human decision-making rather than trying to automate the decision itself.

James—skeptical, gruff James—proposed using computer vision AI to detect potential safety hazards in the warehouse, giving him superhuman awareness without replacing his judgment about what to do with that information.

This is what effective human-AI collaboration actually looks like: not humans working for machines, but machines working for humans.

Research from MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society demonstrates that the most successful AI implementations follow what they call the “principle of human primacy”—systems designed to enhance human capabilities while preserving human agency and decision-making authority (MIT IDSS, 2024). Organizations that follow this principle see 250% higher ROI on AI investments compared to those that treat AI as a human replacement (MIT IDSS, 2024).

The redesign took three months. It was messy, contentious, and frequently derailed by arguments about whether the AI should be allowed to suggest break times (consensus: absolutely not, that’s creepy). But something fundamental had shifted.

The technology hadn’t changed. The humans had—specifically, their relationship to the technology.

Chapter Eight: The Reckoning

Six months after discovering the “Humans First” channel, Margot found herself in a very different boardroom conversation.

The CFO, who’d spent the previous year demanding harder ROI metrics and faster productivity gains, was reviewing the latest performance data with an expression that suggested he’d bitten into what he thought was a brownie but turned out to be a bran muffin.

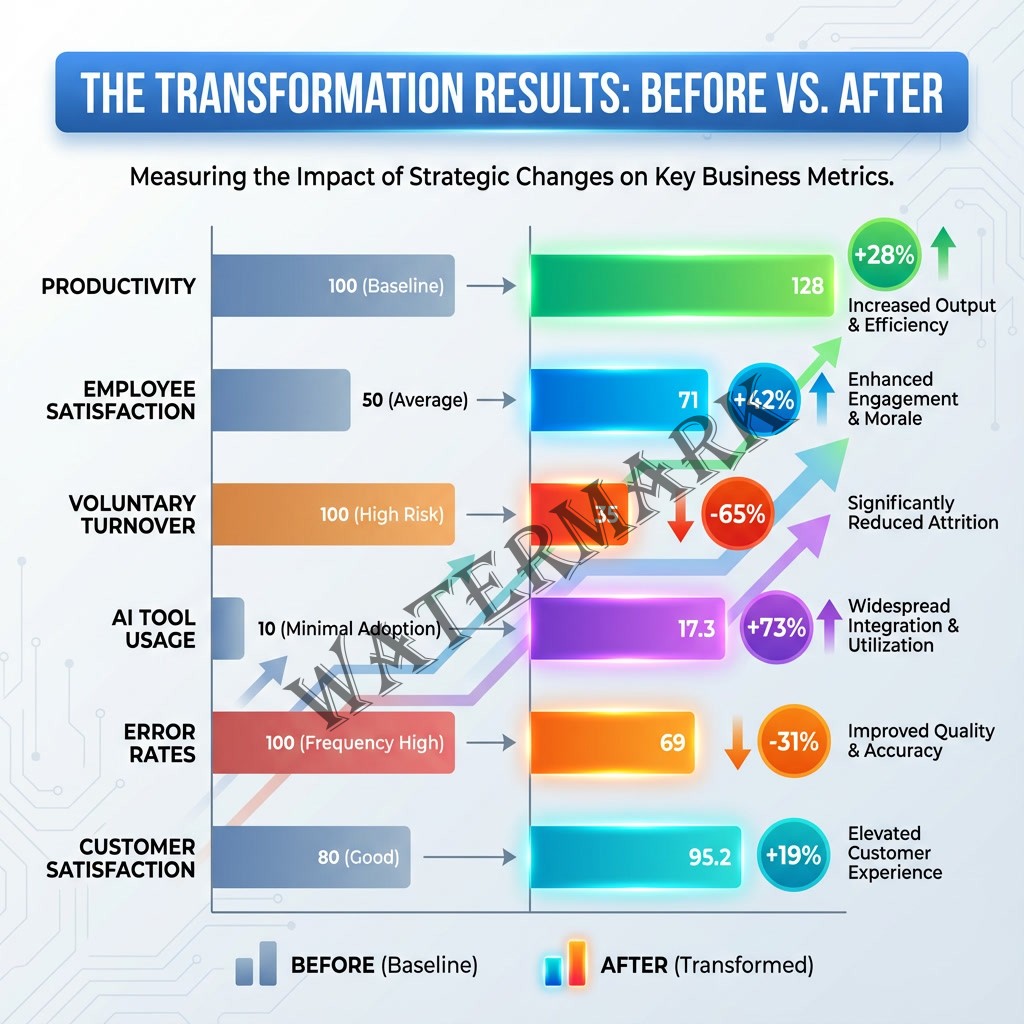

“Let me make sure I understand this,” he said. “We reduced our AI toolset by 40%, increased human override rates to 35%, and… somehow productivity is up 28%?”

Margot smiled. “Turns out people work better when they’re not actively sabotaging the systems they’re supposed to use.”

Employee satisfaction scores had jumped 42%. Voluntary turnover had dropped to the lowest rate in AeroStream’s history. The “Humans First” channel still existed, but its most recent post was a meme celebrating how the AI had correctly predicted a supply chain disruption that human analysts had missed—along with three paragraphs analyzing why it had caught something they hadn’t, turning it into a learning opportunity.

But the most significant change wasn’t captured in any metric.

Sarah had become the company’s de facto AI literacy champion, running training sessions that focused on understanding AI limitations rather than just capabilities. Marcus had developed a system for documenting when human judgment overrode AI suggestions, creating a feedback loop that actually improved the algorithms over time. The warehouse team had turned AI adoption into a collaborative game, competing to find the most creative ways to combine human expertise with machine assistance.

The resistance hadn’t disappeared—it had transformed into partnership.

This aligns with research from Deloitte on successful AI transformation. Their 2024 study found that organizations with the highest AI maturity share a common characteristic: they treat AI adoption as a “sociotechnical challenge” requiring equal attention to technology, processes, and people. These organizations see 4.2 times higher value realization from AI investments (Deloitte, 2024).

Closing: The Human Victory

Late one Friday evening, Margot found herself back in Conference Room C with Sarah, working on a presentation about their redesigned AI strategy for an industry conference.

“You know what’s funny?” Sarah said, highlighting a particularly impressive efficiency metric. “When we started this, I was terrified the AI would take my job. Now I can’t imagine doing my job without it.”

“What changed?” Margot asked, though she suspected she knew the answer.

“You stopped treating us like obstacles to overcome and started treating us like the actual point of the whole exercise.”

There it was.

The great AI reckoning of 2026 isn’t really about AI at all. It’s about remembering that technology serves humanity, not the other way around. It’s about building systems that make humans more human—more creative, more strategic, more fulfilled—rather than making humans more machine-like.

Professor Daron Acemoglu of MIT, winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics, has extensively studied the economic impacts of automation. He warns against what he calls “so-so automation”—technologies that replace human workers without creating substantial new value or capabilities (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2022). His research documents how automation has contributed significantly to income inequality over the past four decades, particularly when it displaces workers without creating new tasks where human labor maintains comparative advantage.

The alternative, Acemoglu argues, is “augmenting automation”—technologies that enhance human productivity while creating new tasks and opportunities for human expertise. In a 2019 Project Syndicate article, he and co-author Pascual Restrepo emphasized: “AI applications could be deployed to restructure tasks and create new activities where labor can be reinstated, ultimately generating far-reaching economic and social benefits” (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019).

AeroStream had stumbled its way from “so-so” to “augmenting,” but only after learning the hard way that technology adoption is fundamentally a human problem requiring human solutions.

Margot closed her laptop and looked at Sarah. “I’m glad you stayed.”

“Me too,” Sarah said. “Though I’m keeping the ‘Humans First’ channel. You never know when we’ll need to organize another rebellion.”

Margot laughed. “Fair enough. Just let me know before you feed the AI any more Christmas party spreadsheets.”

“No promises.”

As they walked out together, Margot realized that the most valuable thing she’d learned wasn’t in any AI implementation guide or digital transformation framework. It was simpler and infinitely more complex:

The future of work isn’t human or machine. It’s human and machine. But only when the humans get to decide how that “and” actually works.

The mutiny hadn’t destroyed their AI strategy. It had saved it.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019, March). The revolution need not be automated. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ai-automation-labor-productivity-by-daron-acemoglu-and-pascual-restrepo-2019-03

- Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2022). Tasks, automation, and the rise in U.S. wage inequality. Econometrica, 90(5), 1973-2016. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA19815

- Autor, D., & Acemoglu, D. (2024). The labor market impacts of artificial intelligence. MIT Work of the Future Research Brief. https://workofthefuture.mit.edu/research-post/the-labor-market-impacts-of-artificial-intelligence/

- Chui, M., Hazan, E., Roberts, R., Singla, A., Smaje, K., Sukharevsky, A., Yee, L., & Zemmel, R. (2024). The state of AI in 2024: Faster adoption, emerging risks. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

- Crawford, M. B. (2009). Shop class as soulcraft: An inquiry into the value of work. Penguin Books.

- Deloitte. (2024). 2024 Global Human Capital Trends: The new leadership premium. Deloitte Insights. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/human-capital-trends.html

- Kane, G. C., Phillips, A. N., Copulsky, J. R., & Andrus, G. R. (2024). Redesigning the post-digital organization. MIT Sloan Management Review, 65(2), 1-8. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/redesigning-the-post-digital-organization/

- Kanter, R. M. (n.d.). Change is disturbing when it is done to us, exhilarating when it is done by us [Quote]. In Rosabeth Moss Kanter quotes. Goodreads. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7683962

- MIT IDSS (Institute for Data, Systems, and Society). (2024). Principles for human-centered AI design. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://idss.mit.edu/research/human-centered-ai/

- Nadella, S. (2024, January 16). Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella talks AI at Davos [Interview]. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/16/tech/microsoft-ceo-satya-nadella-talks-ai-at-davos/index.html

- Nadella, S. (2026, January 2). Looking ahead to 2026 [Blog post]. SN Scratchpad. Cited in: Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella calls for consensus about AI. The Register. https://www.theregister.com/2026/01/02/microsoft_ceo_satya_nadella_calls

- Stanford HAI (Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence). (2024). AI literacy in the enterprise: A framework for training and adoption. Stanford University. https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ai-literacy-enterprise-framework-training-and-adoption

Additional Reading

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2023). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies (2nd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

- Davenport, T. H., & Kirby, J. (2024). Beyond automation: The human-AI partnership. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Kanter, R. M. (2020). Think outside the building: How advanced leaders can change the world one smart innovation at a time. PublicAffairs.

- Leonardi, P. M., & Neeley, T. B. (2022). The digital mindset: What it really takes to thrive in the age of data, algorithms, and AI. Harvard Business Review Press.

- West, D. M. (2018). The future of work: Robots, AI, and automation. Brookings Institution Press.

Additional Resources

- MIT Work of the Future Initiative

https://workofthefuture.mit.edu

Comprehensive research on the changing nature of work in the age of AI and automation. - Stanford Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI)

https://hai.stanford.edu

Research and resources on developing AI that augments human capabilities and respects human values. - Partnership on AI

https://partnershiponai.org

A multi-stakeholder organization studying and formulating best practices on AI technologies. - McKinsey Global Institute – Future of Work

https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/future-of-work

Data-driven insights on automation, AI, and workforce transformation. - Deloitte AI Institute

https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/deloitte-analytics/topics/artificial-intelligence.html

Research and practical guidance on AI implementation and organizational change.

Leave a Reply