China’s Social Credit System isn’t what you think. Individual scores faded,

corporate compliance exploded, and AI governance went global.

Editor’s Note: We Reopened the File

Last year, we published a deep dive into China’s AI-powered Social Credit System. Like most serious analyses at the time, it focused on individual scoring, surveillance fears, and dystopian speculation.

China’s AI-Powered Social Credit System: Navigating the Digital Trust Frontier

That story is now outdated.

In just ten months, China quietly rewired the system. Individual citizen scoring was largely shelved. Corporate compliance became the core. Credit repair was formalized. And what emerged is no longer a social experiment—but a trillion-dollar governance infrastructure shaping financing, trade, and regulation inside China and beyond.

This new deep dive is a forensic reassessment.

We revisit what we got right, what we missed, and what changed after China’s March 2025 policy reset. We trace how social credit evolved from a controversial idea into a scalable model of algorithmic governance—one increasingly exported globally and mirrored, more quietly, in Western systems under different names.

If you’re still thinking about social credit as a “score,” you’re missing the real story.

This is about trust becoming infrastructure.

Compliance becoming capital.

And AI-driven governance becoming normal—faster than anyone expected.

Executive Summary: Ten Months Changed Everything

In April 2025, we published what we believed was a comprehensive investigation into China’s Social Credit System. At the time, the system appeared fragmented, experimental, and only partially implemented. We described it as a bold attempt to quantify trust, raised concerns about algorithmic morality, and focused heavily on individual scoring pilots that had drawn global attention. That analysis was not wrong—but it was incomplete.

Ten months later, the landscape has changed in ways that fundamentally alter how the system should be understood.

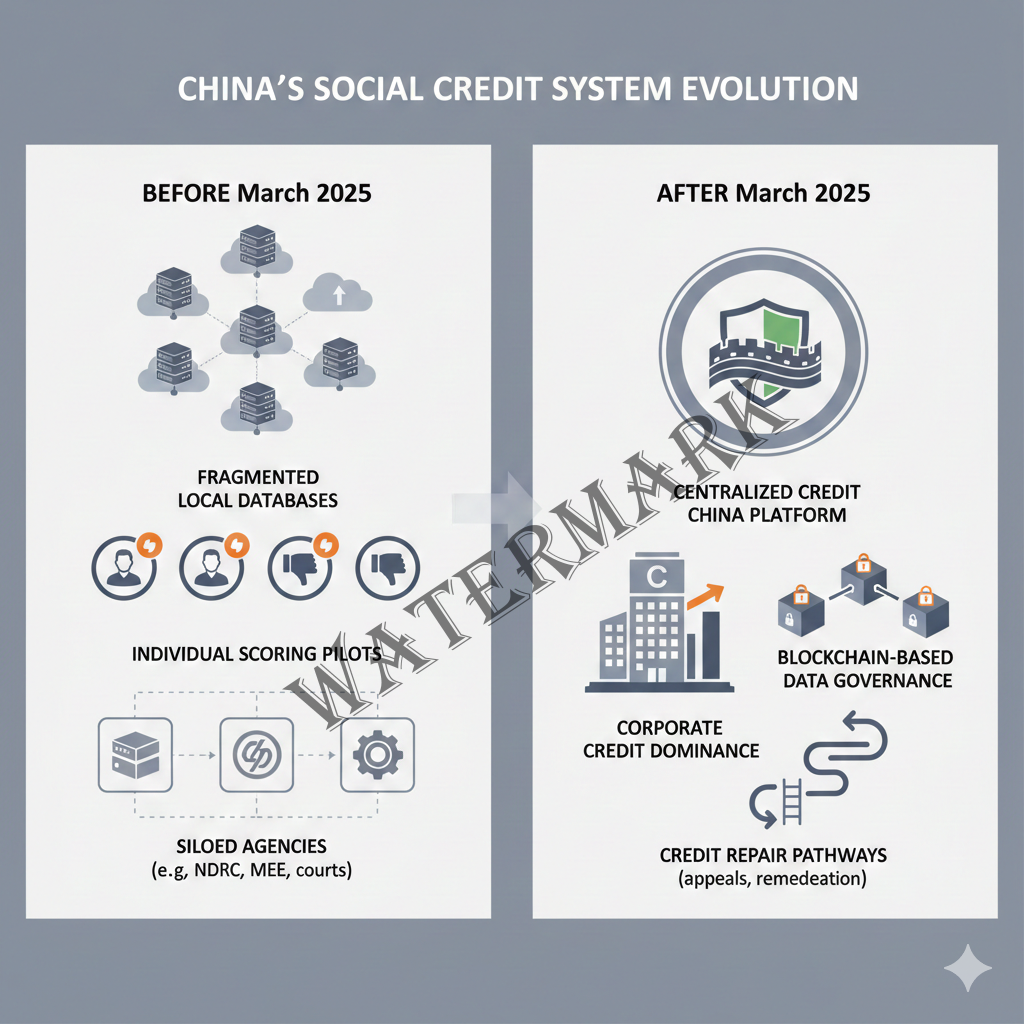

Three developments, in particular, rewrote the story. First, a sweeping State Council policy issued in March 2025 reorganized the system’s legal, technical, and governance foundations. Second, most local experiments involving comprehensive individual citizen scoring were quietly wound down, placing the most feared version of the system on indefinite hold. Third—and most consequentially—the Corporate Social Credit System emerged as the primary operational core, processing trillions of dollars in financing and regulatory decisions.

This evolution matters because the real impact of social credit is no longer centered on individual punishment. It is embedded in the infrastructure of business compliance, financial access, and cross-border governance. China is not merely building a domestic trust system. It is exporting the technical and normative architecture of algorithmic governance to the rest of the world.

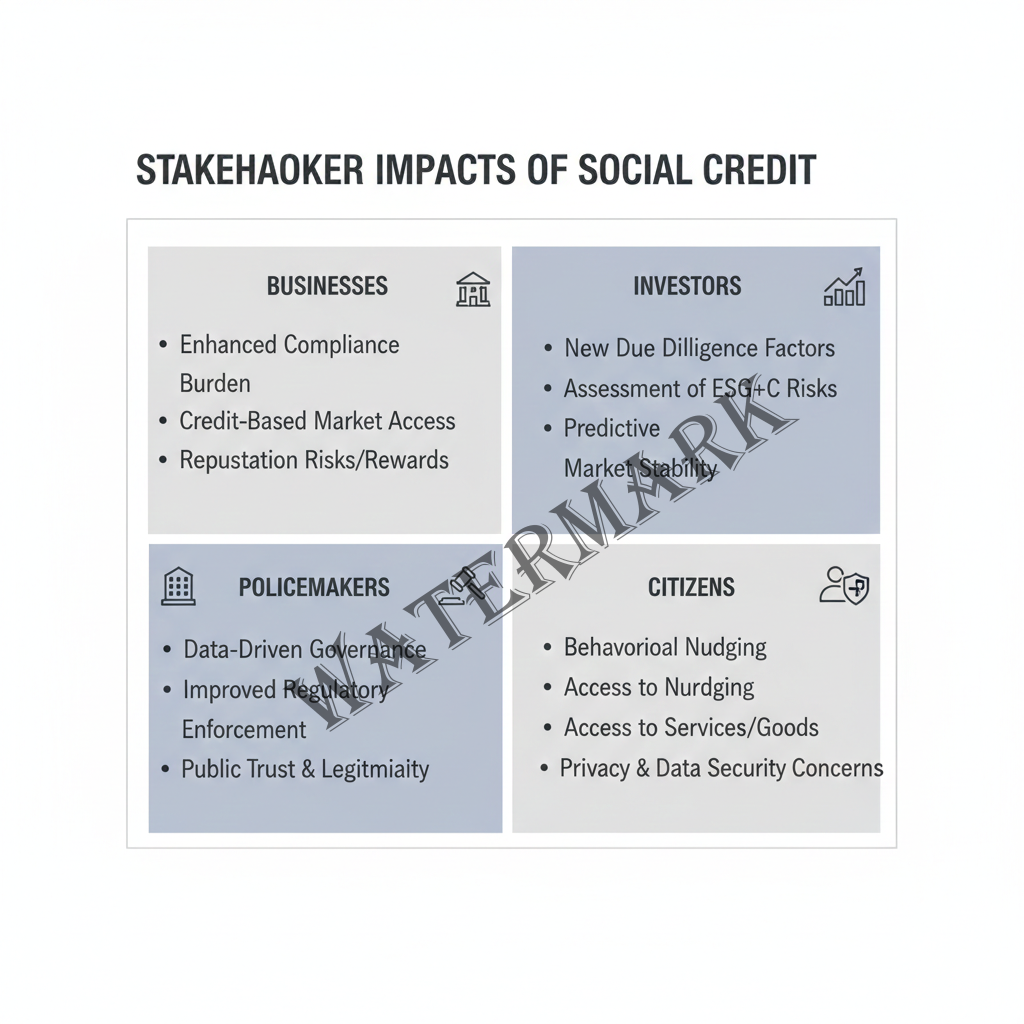

This document delivers a forensic reassessment of our earlier analysis, drawing on policy changes, market data, and international deployment patterns. It explains what we got right, what we missed, and why misunderstanding the system’s current form is far more dangerous than overstating its dystopian potential. Understanding this shift is not an academic exercise. It is now a matter of strategic, economic, and civic relevance for businesses, investors, policymakers, and citizens alike.

Chapter One: A Forensic Audit of the Original Analysis

Our April 2025 assessment correctly identified one critical truth: China’s Social Credit System was never a single, unified score governing every citizen. Instead, it functioned as a loose constellation of sector-specific and regionally implemented initiatives. This fragmentation was not a bug; it was an acknowledged feature of a system still under construction.

The March 2025 State Council directive confirmed this reality explicitly, citing inconsistent regulatory frameworks and insufficient data integration as structural weaknesses that needed correction. In this respect, our original framing aligned closely with the government’s own internal diagnosis.

We were also directionally correct in anticipating that corporate compliance would become central. What we underestimated was the speed and scale with which this transition would occur. By early 2026, the Corporate Social Credit System had become the system’s operational heart. It now processes approximately ¥37.3 trillion in financing, including more than ¥9 trillion in compliance-linked credit for small and medium enterprises. This alone places it on a scale comparable to the largest national banking infrastructures in the world.

Where we misjudged the trajectory was in our emphasis on individual scoring. The scenarios we described—citizens receiving benefits for socially approved behavior or facing travel restrictions for infractions—were not fictional. They occurred in pilot cities. What we failed to anticipate was how quickly these programs would be deprioritized once public backlash, administrative complexity, and legal ambiguity became clear.

By January 2026, most comprehensive individual scoring trials had ended. The feared nationwide citizen score did not materialize. This does not mean individual surveillance vanished; it means that governance shifted toward a less visible but more economically consequential mechanism.

We also failed to anticipate the introduction of formal credit repair mechanisms. The November 2025 regulations established structured pathways for companies to remove negative records after demonstrating corrective action and sustained compliance. This change transformed the system from a purely punitive model into one that explicitly acknowledged institutional redemption.

Finally, our initial treatment of privacy concerns underestimated the degree to which technical solutions would be deployed to address them. The new framework emphasizes data accessibility without public visibility, using blockchain-based traceability to record every instance of data access. This approach reflects a more sophisticated governance model than the simplistic surveillance narrative often presented in Western media.

Taken together, these developments suggest our original analysis captured the system’s intent but underestimated its capacity for rapid structural adaptation.

Chapter Two: The March 2025 Policy Transformation

On March 31, 2025, China’s State Council and Communist Party Central Committee released a 23-point policy document that quietly redefined the Social Credit System’s purpose and architecture. While global attention remained focused on high-profile AI controversies elsewhere, this directive laid the groundwork for a far more consequential shift.

The policy mandated the creation of a unified national disclosure architecture, designating the Credit China platform as the sole authorized portal for public credit information. Government agencies were explicitly prohibited from unauthorized data sharing, and third-party exploitation of public credit data was restricted. This represented a move away from fragmented experimentation toward centralized oversight.

Equally important was the introduction of a new data governance principle: information should be usable for authorized purposes without being broadly visible. In practice, this means data can influence decisions—such as financing eligibility or regulatory scrutiny—without being openly downloadable or publicly displayed. Blockchain-based traceability ensures that every access is logged, creating a technical audit trail rather than relying solely on policy enforcement.

The directive also formalized structured credit repair. Entities placed on serious discredit lists must now be given clear procedures for reinstatement once compliance is restored. This approach reflects economic pragmatism rather than leniency. Permanently excluding companies from markets reduces innovation, investment, and employment. A system that allows correction while preserving deterrence is more sustainable.

Perhaps the most internationally significant element of the policy was its explicit support for exporting credit service standards. The document encourages Chinese credit institutions to participate in international standard-setting and cross-border recognition frameworks. In practical terms, this means Chinese credit assessments may increasingly influence access to financing, contracts, and partnerships beyond China’s borders.

By early 2025, the National Credit Information Sharing Platform had already accumulated more than 80 billion records covering approximately 180 million businesses. The scale of this data infrastructure is difficult to overstate. It represents not merely surveillance, but a new mechanism for allocating economic trust at unprecedented scale.

Chapter Three: The Belt and Road Surveillance Corridor

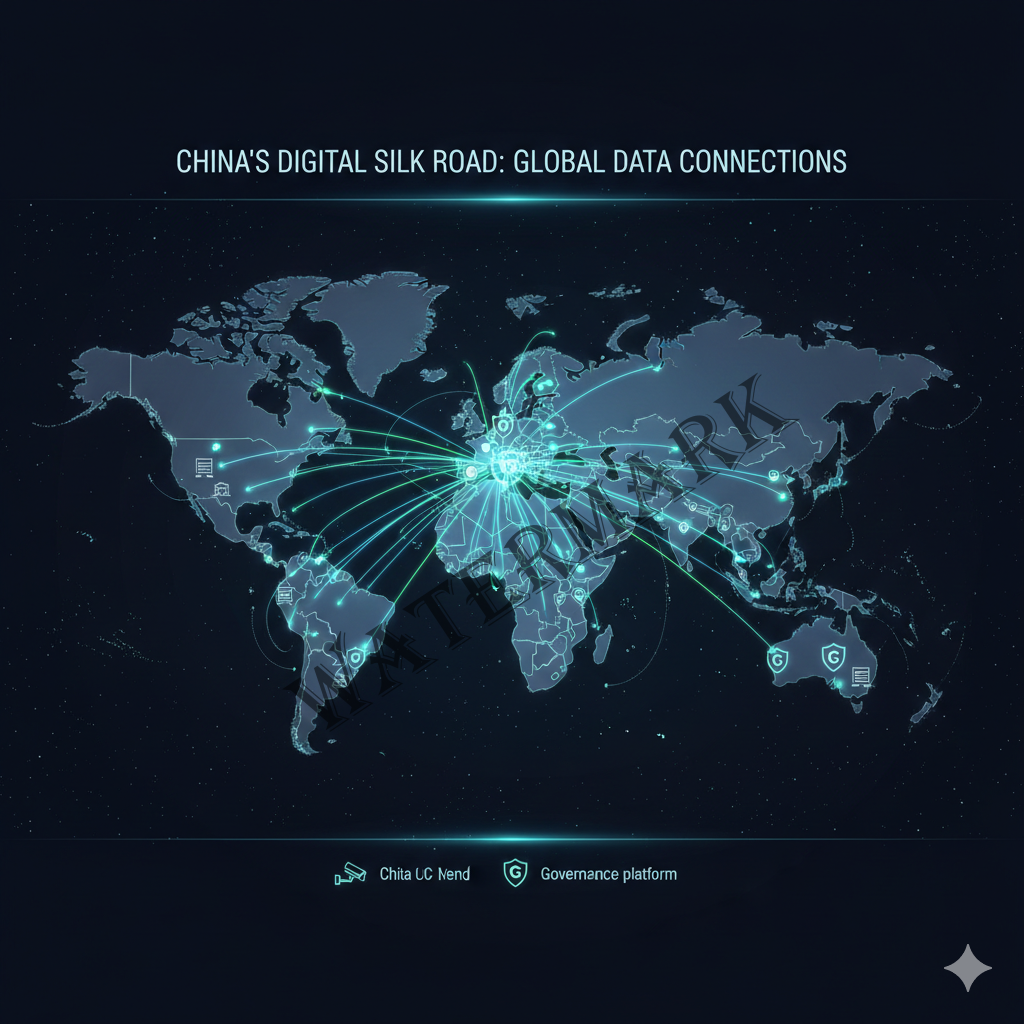

While international commentary continues to fixate on surveillance cameras in Chinese subways or facial recognition in domestic policing, a far more consequential development has unfolded quietly across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China has begun constructing what may be the world’s first transnational infrastructure for algorithmic governance.

Since 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative has committed more than one trillion dollars to infrastructure projects spanning over 150 countries. Ports, railways, power grids, and telecommunications networks are the visible components of this effort. Less visible—but arguably more significant—is the export of integrated digital governance systems embedded within these projects.

These systems are not limited to physical surveillance hardware. They include centralized command platforms, data aggregation software, behavioral analytics, and compliance scoring architectures that mirror China’s own domestic systems. When adopted by partner countries, they reshape how populations are monitored, how risk is assessed, and how state authority is exercised.

Ecuador offers one of the earliest and clearest examples. Beginning in 2011, the government implemented a nationwide integrated security platform known as ECU-911, constructed by a Chinese state-owned enterprise. The system connects thousands of cameras across major cities into a centralized command center capable of real-time monitoring, behavioral analysis, and coordinated response. While marketed as a public safety tool, the system’s design allows for political monitoring, crowd analysis, and persistent tracking. Maintenance contracts require ongoing access by Chinese technical teams, creating long-term dependency and external data exposure.

Venezuela followed with a more explicit adaptation of social credit logic. The “Fatherland Card” system, built by a Chinese telecommunications firm, links political affiliation, social benefits, and access to essential services within a unified digital identity. Over twenty million citizens now participate in a system where algorithmic assessments influence food access, healthcare eligibility, and employment opportunities. The technical architecture closely resembles early Chinese individual credit pilots, down to database structures and behavioral tracking logic.

In Zimbabwe, the export relationship took on a more troubling dimension. Facial recognition infrastructure installed by a Chinese AI company included provisions for transferring biometric data back to China to improve algorithm performance. In effect, Zimbabwean citizens became involuntary training data for surveillance systems later deployed worldwide.

Similar deployments have since occurred in Kenya, Serbia, Pakistan, and dozens of other countries. Each installation follows a consistent pattern: hardware provision, software integration, technical dependency, and standards adoption. Over time, these systems lock recipient countries into Chinese technical ecosystems that are difficult and costly to replace.

This matters because the March 2025 policy directive explicitly encourages Chinese credit institutions and technology providers to participate in international standard-setting. When governance infrastructure becomes standardized across multiple jurisdictions, the definitions of trustworthiness, compliance, and risk embedded in that infrastructure gain extraterritorial influence.

What emerges is not simply surveillance export, but governance export. Countries adopting these systems are not just purchasing technology. They are importing a model of algorithmic authority in which stability is prioritized over individual autonomy and collective outcomes outweigh personal rights.

Chapter Four: Where the System Actually Lives

Despite popular narratives, China’s Social Credit System is not primarily a citizen surveillance regime. It is a regulatory infrastructure designed to govern corporate behavior at scale. Understanding this distinction is essential to understanding how the system actually functions.

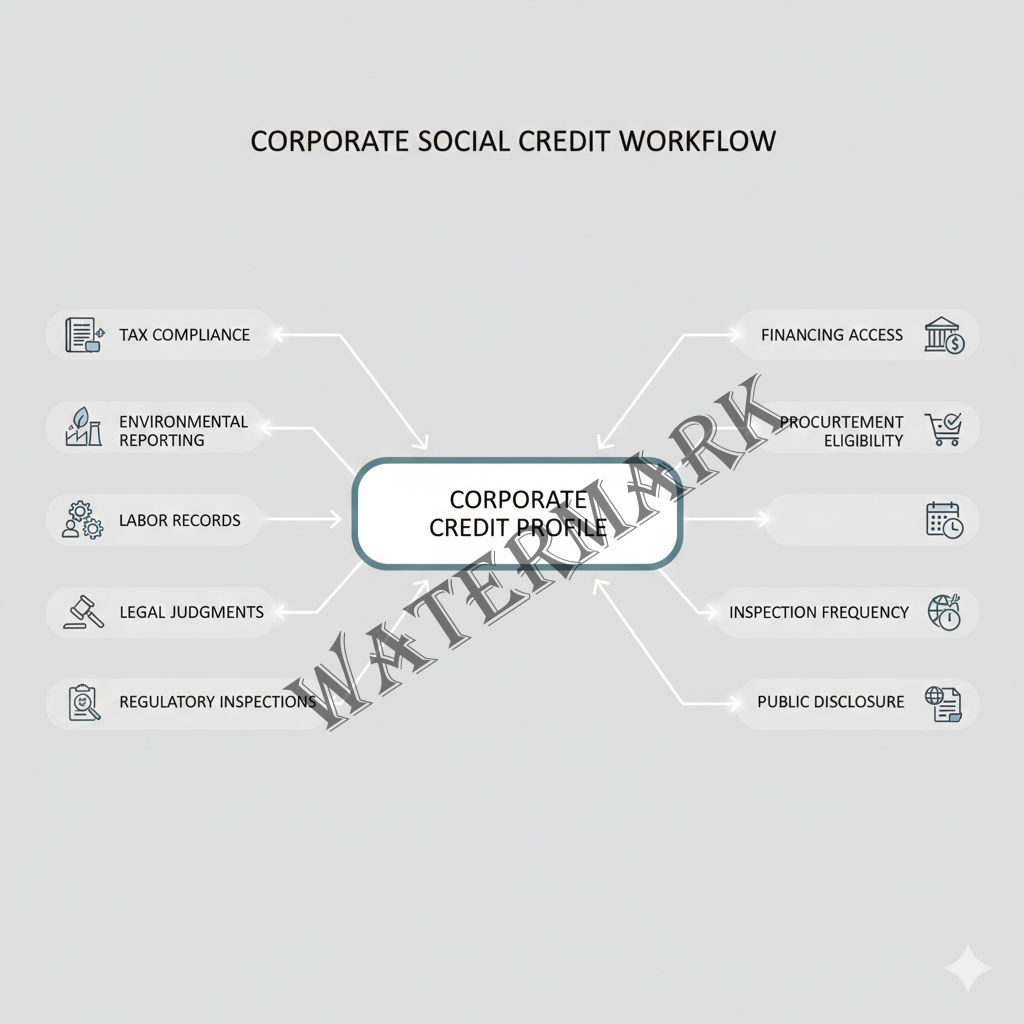

At the center of the system is the Corporate Social Credit System, which assigns every registered business a unified identifier linking tax records, environmental compliance, labor practices, contract performance, regulatory inspections, and legal judgments. These records are aggregated across ministries and local governments, forming a dynamic compliance profile that influences how the state interacts with each entity.

Companies with strong compliance histories receive tangible benefits. Regulatory approvals are processed faster, inspections are less frequent, financing terms improve, and access to government procurement expands. Companies with poor records face the opposite. Increased scrutiny, restricted financing, delayed customs clearance, and public disclosure of violations create cascading operational consequences.

The system categorizes entities into tiers based on behavior. At the highest level are firms deemed trustworthy, which receive preferential treatment across multiple regulatory domains. At the other extreme are entities designated as seriously untrustworthy, often referred to as blacklisted. These designations trigger coordinated sanctions across agencies, effectively isolating the company from critical economic functions.

Between these extremes exists a growing emphasis on correction rather than permanent exclusion. The introduction of structured credit repair allows companies to remediate violations, demonstrate sustained compliance, and restore their standing. This approach reflects a recognition that economic vitality depends on the ability of firms to recover from mistakes rather than being permanently excluded.

The real-world consequences of blacklisting are severe. Companies experience reduced access to credit, higher borrowing costs, longer customs clearance times, and loss of tax incentives. For mid-sized firms, these impacts can threaten solvency within a single fiscal year. Multinational companies face additional complexity, as violations by one subsidiary can trigger heightened scrutiny across affiliated entities.

Research suggests the system is achieving some of its stated goals. Studies indicate improvements in environmental compliance, food safety, and contract enforcement in regions where corporate credit mechanisms are fully implemented. At the same time, critics warn that the system fuses state capitalism with surveillance logic, concentrating decision-making power within a technocratic bureaucracy that may overestimate its capacity to evaluate market behavior.

This dual reality—measurable efficiency gains alongside profound governance risks—defines the true nature of China’s social credit architecture.

Chapter Five: The Surveillance Industrial Complex

China’s Social Credit System does not exist in isolation. It is embedded within a rapidly expanding surveillance industrial complex that combines state objectives, commercial incentives, and artificial intelligence development into a mutually reinforcing ecosystem. Understanding this complex is essential to understanding how social credit evolved from a policy experiment into a scalable governance model.

At the center of this ecosystem are large technology firms that operate at the intersection of public security, data analytics, and AI research. Companies such as Hikvision, Dahua, SenseTime, Megvii, and iFlytek provide facial recognition, voice analysis, predictive analytics, and large-scale data processing tools used across policing, transportation, healthcare, and financial regulation. These firms benefit from guaranteed domestic demand, extensive government contracts, and access to enormous datasets generated by public-sector deployment.

Social credit acts as both a customer and a catalyst within this system. The demand for compliance scoring, risk prediction, and behavioral analysis creates continuous incentives to improve algorithmic accuracy. Each new deployment generates additional data, which in turn improves model performance and expands the range of possible applications. This feedback loop blurs the distinction between governance and experimentation.

Crucially, many of these technologies are dual-use by design. Systems marketed as traffic optimization platforms can be repurposed for crowd monitoring. Corporate compliance analytics can be adapted for political risk assessment. Health code infrastructure introduced during public health emergencies can persist long after the emergency ends, quietly integrating into broader governance frameworks.

The international implications of this industrial complex are profound. Chinese firms exporting surveillance and credit infrastructure often bundle hardware, software, training, and financing into turnkey solutions. Recipient countries receive functional systems quickly and at lower cost than Western alternatives. In exchange, they accept technical dependency, limited transparency, and governance models shaped by Chinese regulatory assumptions.

Western export controls and sanctions have attempted to constrain this expansion, but with limited success. In many cases, restrictions have accelerated domestic substitution within China while encouraging firms to deepen partnerships in non-Western markets. The result is a bifurcated global surveillance economy in which competing standards and norms evolve in parallel.

The social credit system benefits directly from this dynamic. As surveillance technologies improve and proliferate, the system’s capacity to ingest, analyze, and act upon data expands. Governance becomes less about explicit rules and more about probabilistic assessments generated by machines trained on massive behavioral datasets.

This transformation raises a difficult question: when governance decisions are increasingly automated, who is accountable for their outcomes? In China’s model, accountability is diffused across technical systems, administrative agencies, and algorithmic processes. This diffusion may enhance efficiency, but it also obscures responsibility in ways that challenge traditional legal and ethical frameworks.

Chapter Six: The AI Infrastructure Reality

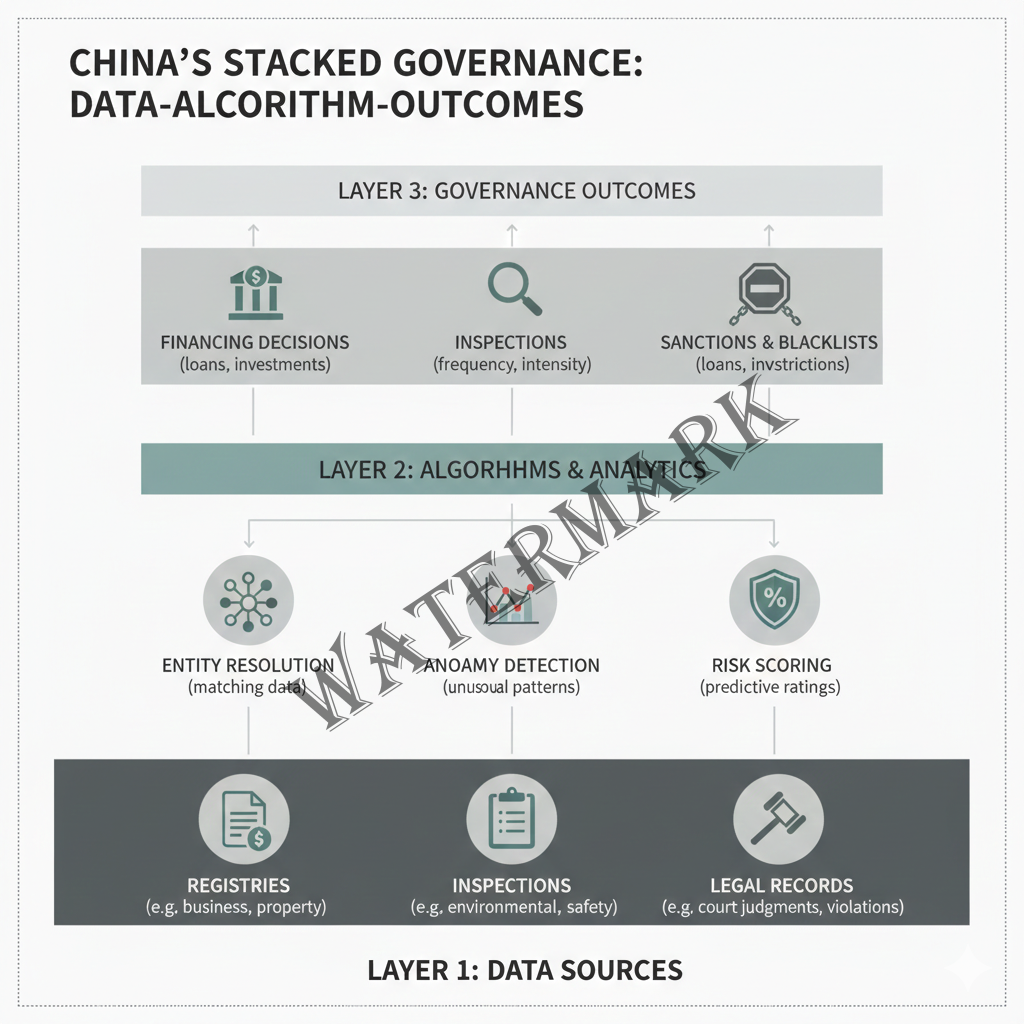

Public discussions of China’s Social Credit System often assume the existence of a single, omniscient artificial intelligence continuously evaluating every citizen. In reality, the system operates on a far more fragmented—and more realistic—technical foundation.

Rather than one unified AI, the system relies on a network of specialized models optimized for specific tasks. These include entity resolution algorithms that link records across databases, anomaly detection systems that flag unusual behavior, natural language processing tools that analyze legal documents and complaints, and risk-scoring models that estimate the likelihood of noncompliance.

Most of these systems are not particularly advanced by cutting-edge AI standards. Many rely on gradient-boosted decision trees, logistic regression, and rule-based systems augmented by machine learning components. Their power lies not in sophistication, but in scale. When deployed across tens of millions of entities and billions of records, even modest predictive accuracy produces significant governance effects.

Data quality remains a persistent challenge. Records collected by different agencies vary in accuracy, timeliness, and completeness. Errors propagate easily across interconnected systems, and mechanisms for correction are unevenly implemented. The introduction of credit repair processes reflects an implicit acknowledgment of these limitations.

Importantly, human discretion has not been eliminated. Officials retain the authority to override algorithmic recommendations, initiate inspections, and interpret results. However, as systems grow more complex and workloads increase, human oversight increasingly becomes procedural rather than substantive. Decisions are often guided by algorithmic outputs that few officials fully understand or feel empowered to challenge.

This dynamic mirrors trends observed in Western algorithmic governance, from credit scoring and predictive policing to content moderation and fraud detection. The difference is one of visibility rather than substance. In China, algorithmic authority is explicit and state-directed. In the West, it is often privatized and obscured behind corporate decision-making.

The infrastructure reality suggests a future in which governance everywhere becomes more automated, probabilistic, and data-driven. China’s social credit system is not an outlier in this respect. It is an early and unusually transparent example of a broader global shift.

Chapter Seven: What This Means for You

For all the abstractions surrounding artificial intelligence and governance, China’s Social Credit System produces consequences that are concrete, immediate, and unevenly distributed. These consequences differ depending on whether you are a business operator, an investor, a policymaker, or an ordinary citizen, but they share a common feature: algorithmic assessments increasingly shape access to opportunity.

For businesses operating in or with China, the most important fact is that participation is not optional. Every registered entity is already embedded in the corporate credit framework through its unified social credit code. This identifier links together tax compliance, environmental reporting, labor practices, customs records, legal judgments, and sector-specific regulatory obligations. There is no single score to check, but there is an evolving profile that influences how regulators, banks, and partners interact with the firm.

In practical terms, this means compliance failures rarely remain isolated. A labor violation can affect procurement eligibility. An environmental infraction can raise financing costs. A court judgment can trigger increased inspections across subsidiaries. The system’s power lies less in any single sanction than in its capacity to propagate consequences across administrative domains.

The introduction of credit repair mechanisms adds a layer of strategic complexity. Companies that recognize violations early, remediate them fully, and document corrective action can restore standing over time. Those that delay or treat enforcement as a one-off cost often find secondary consequences multiplying. In this sense, the system rewards institutional responsiveness rather than moral virtue.

Investors face a different challenge. Social credit data increasingly functions as a proxy for operational risk, particularly in regions where traditional market signals are weak or distorted. Firms with persistent compliance problems experience higher financing costs, slower approvals, and greater exposure to discretionary enforcement. These risks rarely appear in standard financial disclosures but can materially affect performance.

For policymakers and researchers outside China, the system presents a governance dilemma rather than a technological one. The underlying logic—using data to allocate trust and resources—is not unique to China. What is distinctive is the degree of central coordination and the explicit integration of compliance data into economic decision-making. Whether this model spreads depends less on ideology than on perceived effectiveness.

Citizens, finally, confront a subtler transformation. Even without comprehensive personal scoring, algorithmic governance reshapes everyday interactions with the state. Eligibility checks become automated. Risk assessments become probabilistic. Appeals become procedural. The experience of governance shifts from interpersonal discretion to system-mediated judgment.

Chapter Eight: The Western Mirror

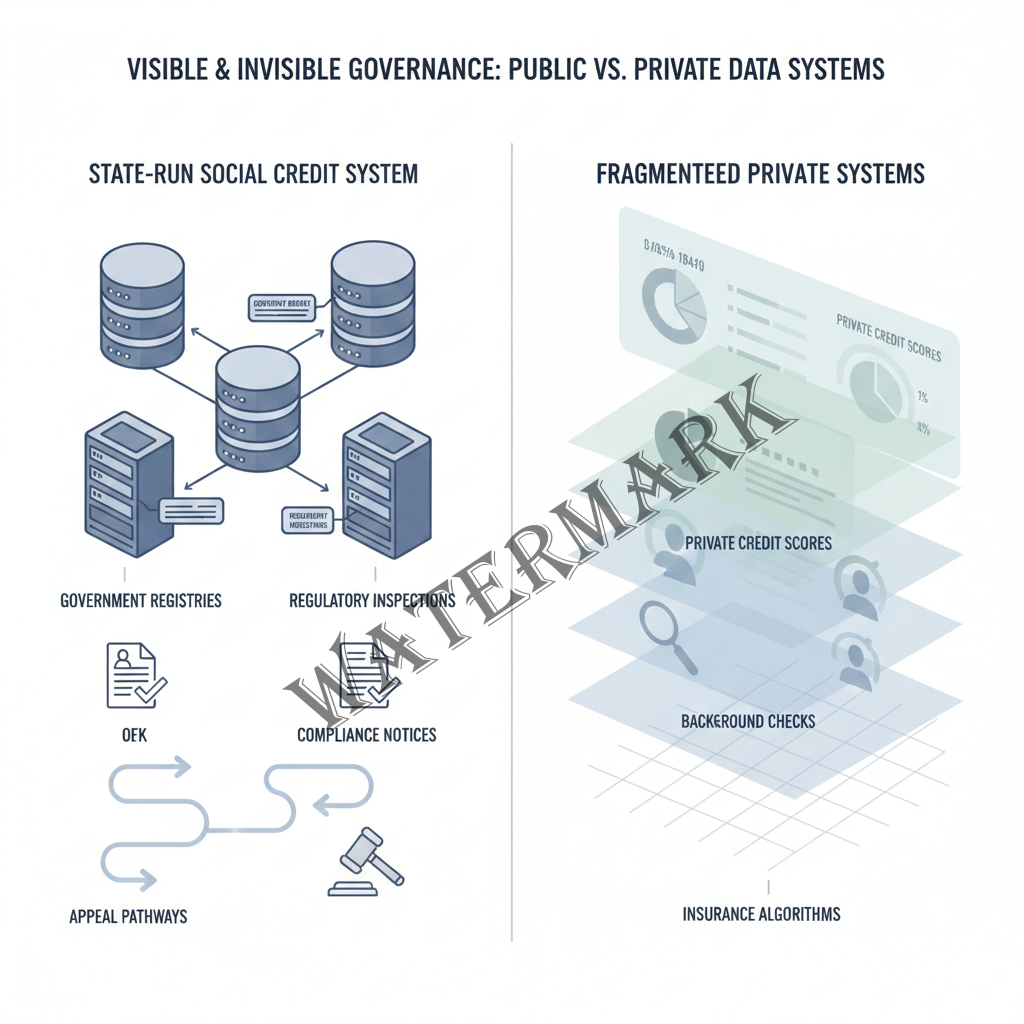

One reason the Chinese Social Credit System attracts such intense scrutiny is that it is visible. It is state-run, explicitly labeled, and openly debated as a governance tool. This visibility makes it easier to critique—and easier to dismiss as uniquely authoritarian.

That dismissal becomes uncomfortable when viewed alongside Western systems that perform similar functions under different names. Credit scores determine access to housing, employment, insurance, and utilities across much of the democratic world. Background checks exclude individuals from professions and opportunities based on opaque criteria. Insurance algorithms price risk using proxies that reproduce historical inequalities. Predictive policing systems allocate enforcement attention based on past data that reflect earlier bias.

The difference is not that Western societies lack algorithmic governance. It is that these systems are fragmented, privatized, and largely invisible. Individuals often do not know when an algorithmic judgment affects them, cannot inspect the underlying logic, and face limited avenues for appeal. Accountability is dispersed across corporations, regulators, and courts in ways that dilute responsibility.

China’s system, for all its coercive potential, makes algorithmic authority legible. Entities can see when they are sanctioned, identify the formal basis for penalties, and pursue remediation through defined channels. This does not make the system just. It makes it structured.

The uncomfortable implication is that the future of governance may converge rather than diverge. As states everywhere grapple with complexity, scale, and limited administrative capacity, algorithmic tools offer efficiency that is difficult to resist. The question is not whether such tools will be used, but how transparently, under what constraints, and with what safeguards.

Framing China’s system as an anomaly risks missing the broader trend. The real contest is not between surveillance and freedom, but between visible governance that can be contested and invisible governance that cannot.

Chapter Nine: What We Still Do Not Know

Despite the scale and maturity the Social Credit System has reached, some of its most important dimensions remain unresolved. These uncertainties are not marginal. They shape how the system may evolve and how much power it ultimately accumulates.

One unresolved issue is legal codification. A comprehensive Social Credit Law has been discussed for years, revised repeatedly, and referenced in policy planning documents, yet it remains unenacted. This absence of a unified legal foundation creates ambiguity. On one hand, it grants authorities flexibility to adjust implementation without legislative friction. On the other, it limits formal avenues for challenge and judicial review. The system operates with real consequences but incomplete legal anchoring.

Effectiveness is another open question. Evidence suggests improvements in areas such as environmental compliance, food safety, and contract enforcement in regions where corporate credit mechanisms are well developed. What remains unclear is whether these gains persist over time or whether firms adapt by optimizing for measured indicators rather than substantive compliance. The difference matters. A system that improves behavior only superficially may erode trust rather than build it.

Perhaps the most difficult unknown is the human cost. Quantitative systems struggle to measure what does not happen: the innovation not pursued because risk feels too costly, the dissent not voiced because consequences are uncertain, the experimentation abandoned because compliance incentives favor caution. These opportunity costs accumulate quietly and resist statistical capture.

Chapter Ten: Where This Is Heading

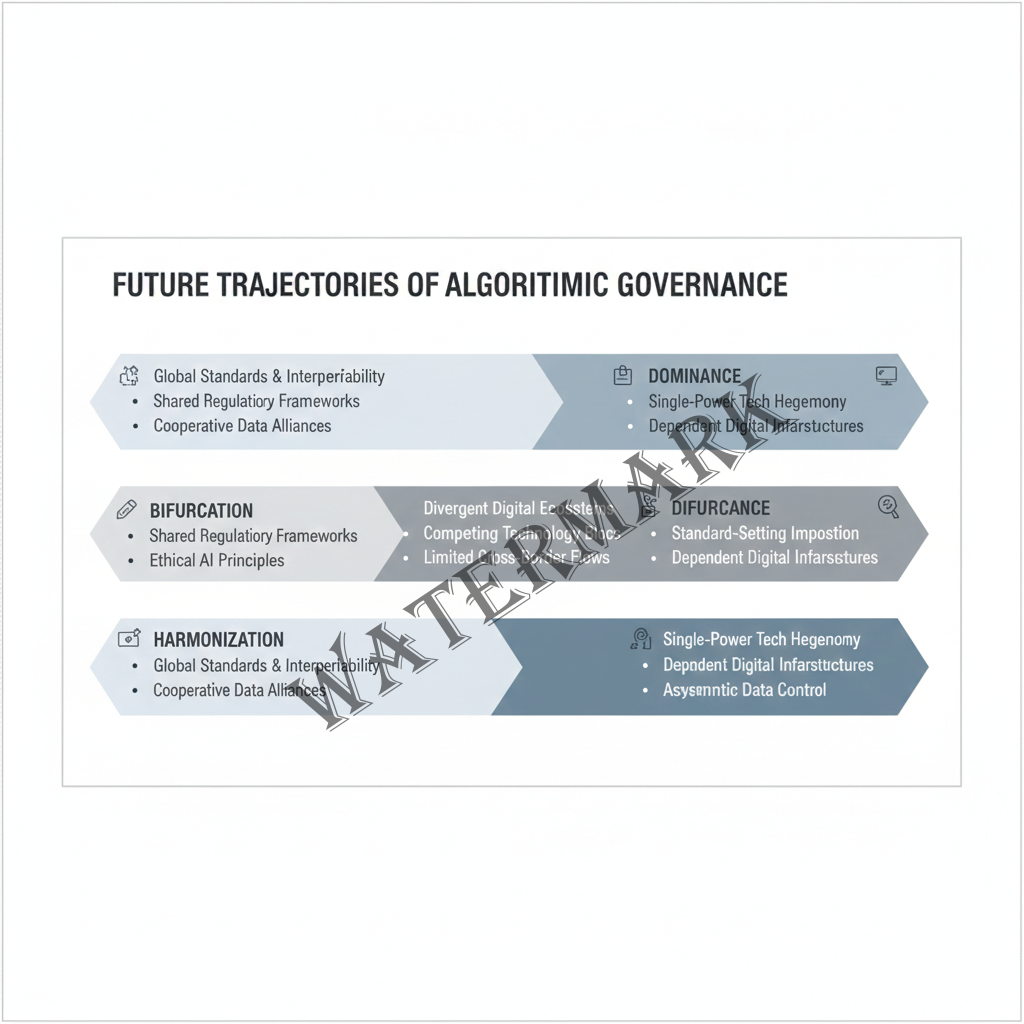

Based on observed implementation patterns, several trajectories appear plausible.

In the near term, corporate social credit will likely continue to expand in scope and technical integration. Credit repair mechanisms will become routinized, spawning professional compliance and remediation services. International standard-setting efforts will intensify, particularly in Belt and Road countries seeking administrative modernization.

Over the medium term, selective individual scoring may return in limited contexts such as financial services, healthcare, or education, where risk-based screening is already normalized. Blockchain-based verification and cross-border data interoperability will further entrench credit records as durable governance artifacts.

In the longer term, algorithmic governance will likely become ordinary rather than exceptional. Social credit may merge with ESG frameworks, digital identity systems, and automated regulatory platforms. The most consequential shift will not be technical, but cultural: the normalization of probabilistic judgment as a basis for allocating opportunity.

The scenario to watch most closely is not authoritarian imposition, but voluntary adoption. If algorithmic governance proves efficient, reduces fraud, and stabilizes markets, political resistance may erode even in societies with strong civil liberties traditions. Efficiency is a powerful argument.

Chapter Eleven: The Final Verdict

Our original analysis was not wrong, but it was incomplete. We correctly identified fragmentation, technological ambition, and ethical risk. We underestimated the system’s adaptability, the centrality of corporate compliance, and the strategic significance of remediation and standard-setting.

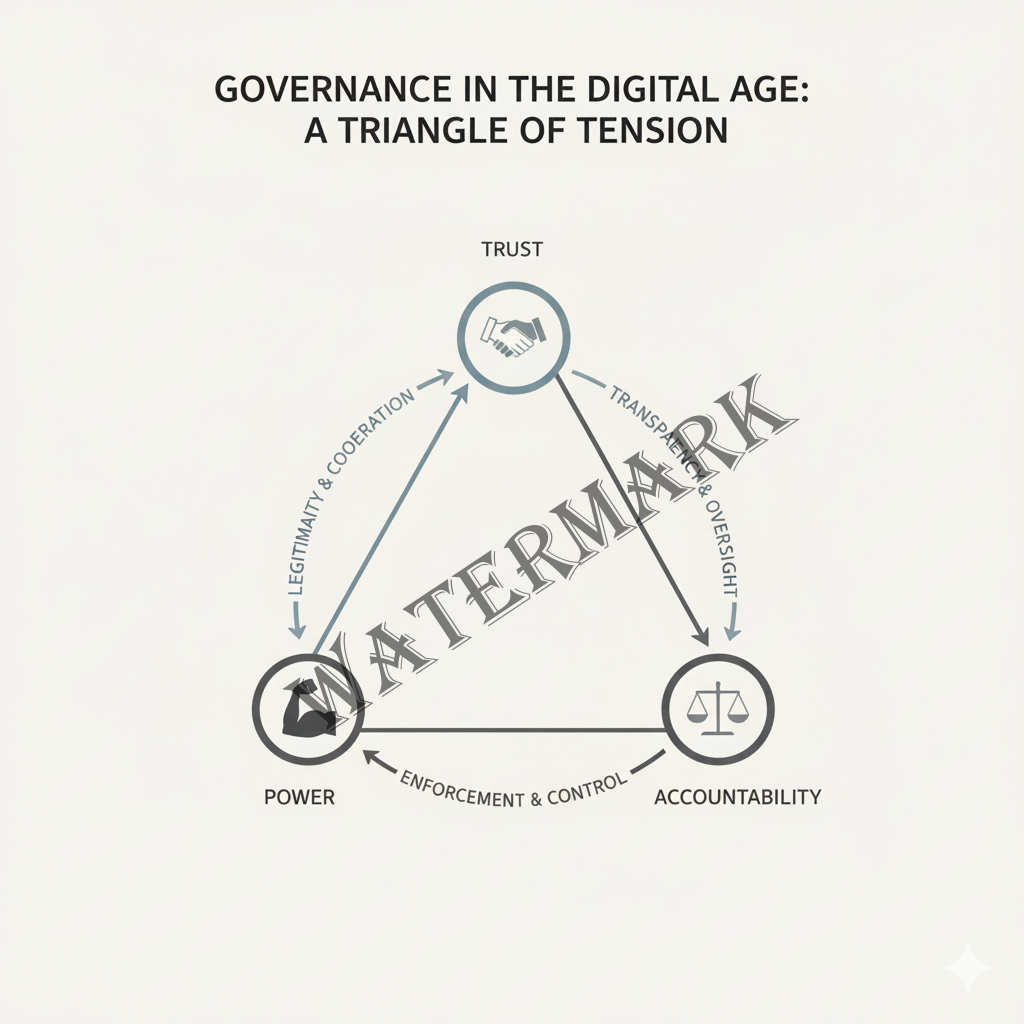

The essential truth remains that algorithmic governance is not an aberration. It is a response to scale, complexity, and administrative constraint. China’s Social Credit System represents one path through that landscape—highly coordinated, explicitly state-driven, and increasingly exportable.

The danger is not that such systems exist. It is that they become normalized without scrutiny. Metrics are never neutral. They encode values, priorities, and power relationships. When trust becomes quantifiable, the question is no longer whether judgment occurs, but who designs the judgment and how it can be contested.

Redemption, transparency, and proportionality are not moral luxuries in such systems. They are structural necessities. Without them, efficiency becomes coercion and governance becomes control.

References

- Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025). Automated repression: AI tools for censorship and surveillance in China. https://www.aspi.org.au

- China Legal Experts. (2025). Using facial recognition in China: What you need to know. https://www.chinalegalexperts.com/news/using-facial-recognition-in-china

- CMS Law. (2025). Corporate reputation in China: Regulatory update of the credit repair mechanism under China’s corporate social credit system. https://cms-lawnow.com

- CNN. (2025, December 4). China’s censorship and surveillance were already intense. AI is turbocharging those systems. https://www.cnn.com

- ChoZan. (2025). China’s social credit system in 2025: How it works and what it really means. https://chozan.co/chinas-social-credit-system/

- Fortune Business Insights. (2025). AI in surveillance market size, industry share & forecast (2025–2032). https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/ai-in-surveillance-market-109303

- Lin, L. Y., & Milhaupt, C. J. (2021). China’s corporate social credit system: The dawn of surveillance state capitalism? European Corporate Governance Institute, Law Working Paper No. 610/2021.

- Mordor Intelligence. (2025). China video surveillance market size, analysis, outlook & share report 2030. https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/china-video-surveillance-market

- MSA Advisory. (2026, January 7). China’s social credit system in 2026: Dispelling common myths. https://msadvisory.com/china-social-credit-system/

- Newsweek. (2025, November 21). How China is changing its social credit system. https://www.newsweek.com/how-china-changing-its-social-credit-system-11079499

- Radio Free Asia. (2025, February 20). China’s homegrown tech boosts global surveillance, social controls. https://www.rfa.org/english/china/2025/02/20/china-ai-neuro-quantum-surveillance-security-threat/

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2025, April 3). China enhances social credit system to boost high-quality development. http://english.scio.gov.cn/pressroom/2025-04/03/content_117803621.html

- World Bank. (2024). Belt and Road Initiative: Economic analysis and policy recommendations. https://www.worldbank.org

- Wu, X., Zhang, Y., & Chen, L. (2025). The improvement of the social credit environment and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from the construction of China’s social credit system. International Review of Economics and Finance, 86, 749–763.

- Zhao, X., Li, H., & Liu, S. (2025). The power of credit: Can the implementation of a social credit system reduce the risk of corporate debt default? Economic Analysis and Policy, 86, 749–763.

Additional Reading

- Brussee, V. (2021). China’s social credit system is actually quite boring. MERICS. https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/chinas-social-credit-system-actually-quite-boring

- Daum, J. (2023). “Franken-Law”: Initial thoughts on the draft social credit law. China Law Translate. https://www.chinalawtranslate.com

- Weber, V. (2024). The AI–surveillance symbiosis in China. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://bigdatachina.csis.org/the-ai-surveillance-symbiosis-in-china/

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

- Yeung, K., & Lodge, M. (Eds.). (2019). Algorithmic regulation. Oxford University Press.

Additional Resources

- China Law Translate — https://www.chinalawtranslate.com

Stanford HAI — https://hai.stanford.edu

MERICS — https://merics.org

Australian Strategic Policy Institute — https://www.aspi.org.au

OECD AI Policy Observatory — https://oecd.ai

Leave a Reply