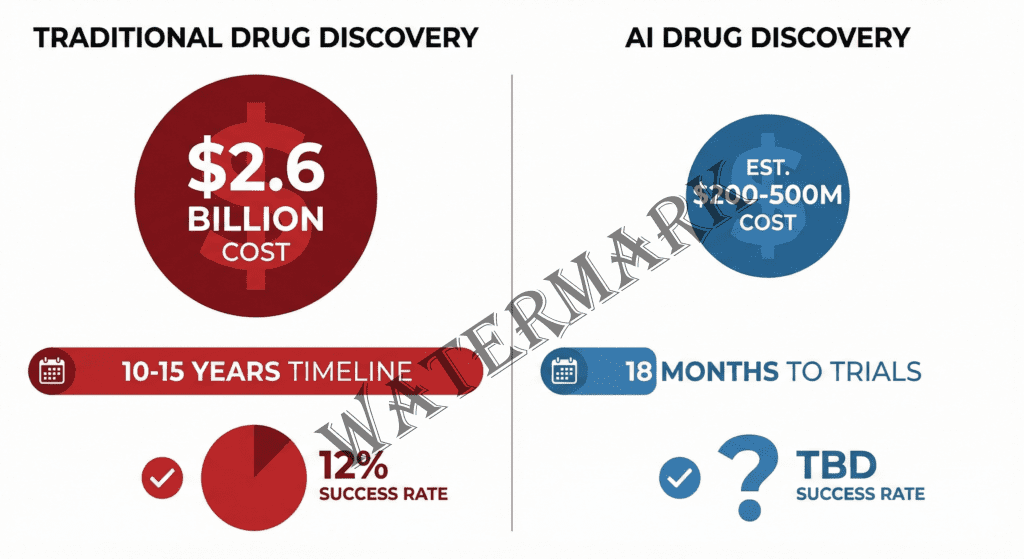

AI promises to transform drug discovery from a $2.6B, decade-long gamble into an 18-month sprint.

But is the revolution real or just expensive hype?

The $2.6 Billion Gamble That AI Wants to Disrupt

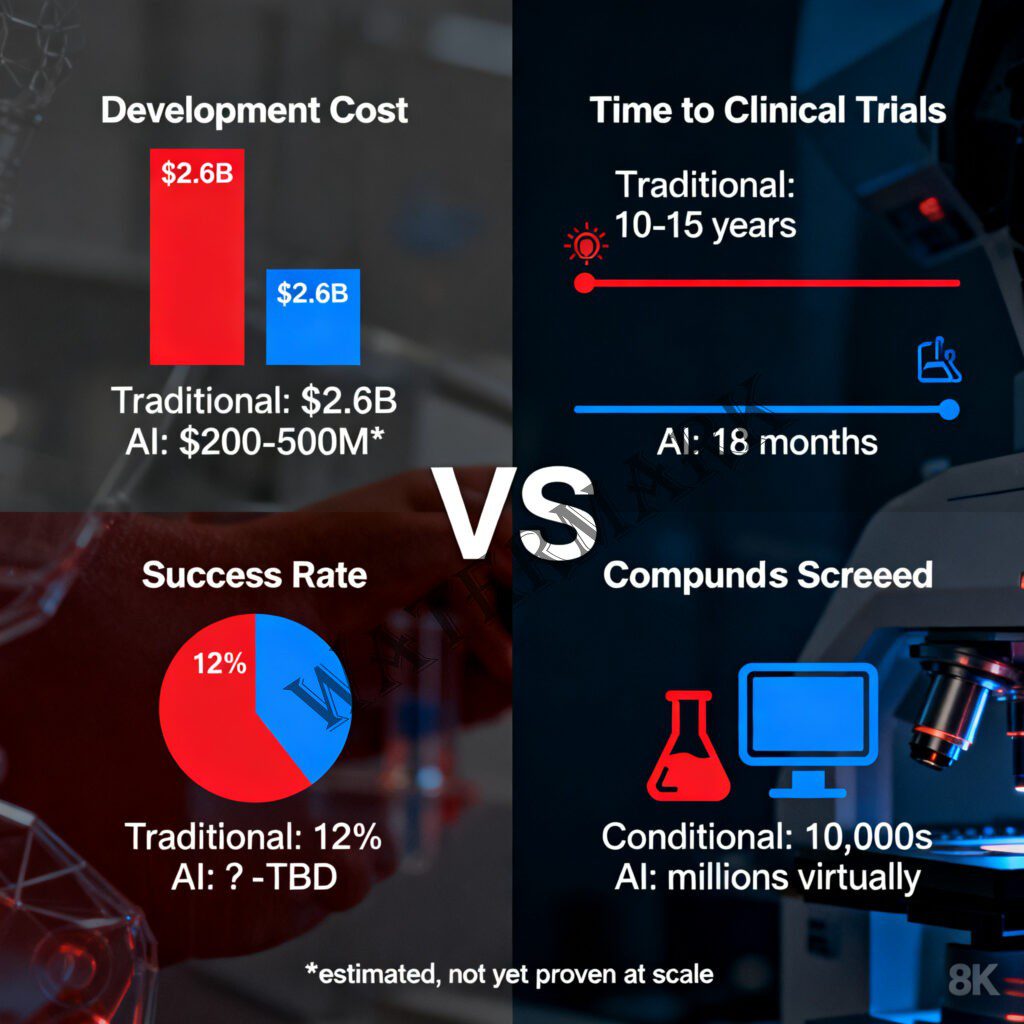

Picture this: You’re a pharmaceutical CEO standing in front of your board, about to greenlight a new drug development program. You know—with stomach-churning certainty—that you’re about to spend the next decade and approximately $2.6 billion on a venture that has a 90% chance of catastrophic failure (Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, 2014). You’ll need to screen millions of compounds, run thousands of experiments, shepherd your candidate through three phases of clinical trials, and pray to the regulatory gods that the FDA smiles upon you. And that’s if everything goes perfectly.

Welcome to traditional drug discovery: a beautiful, maddening, absurdly expensive carnival of human ingenuity where brilliant scientists spend years pipetting liquids into tiny wells, crossing their fingers, and occasionally striking gold. It’s a process that has given us everything from penicillin to immunotherapy, but let’s be honest—it’s also slower than continental drift and more expensive than a small nation’s GDP.

Now imagine a different story. Imagine designing a promising drug candidate not in ten years, but in eighteen months. Imagine screening not thousands of compounds, but millions—virtually, instantly, without a single pipette in sight. Imagine artificial intelligence systems that can predict how a molecule will behave in the human body before you’ve ever synthesized it in a lab.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now, in labs from Boston to Hong Kong, where the marriage of silicon and biology is producing some of the most fascinating—and controversial—developments in modern medicine. But before you get too excited (or too terrified), we need to talk about what’s really going on here. Because the truth about AI drug discovery isn’t quite the “press release miracle” that venture capitalists want you to believe, nor is it the inevitable disaster that skeptics predict.

It’s something far more interesting: a genuine technological revolution that’s still figuring out how to walk.

Chapter One: The Old World—Where Serendipity Costs Billions

Let’s start with a reality check about how drug discovery actually works in the traditional model—because understanding the problem is essential to appreciating why AI might (emphasis on might) be the solution we’ve been waiting for.

The journey from “interesting molecule” to “FDA-approved medication” is a odyssey that would make Odysseus himself give up and go home. The process typically spans 10-15 years and burns through an average of $2.6 billion (Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, 2014). To put that in perspective: you could fund a Mars mission, build a small skyscraper, or produce roughly 100 Hollywood blockbusters for the same price as getting one drug to market.

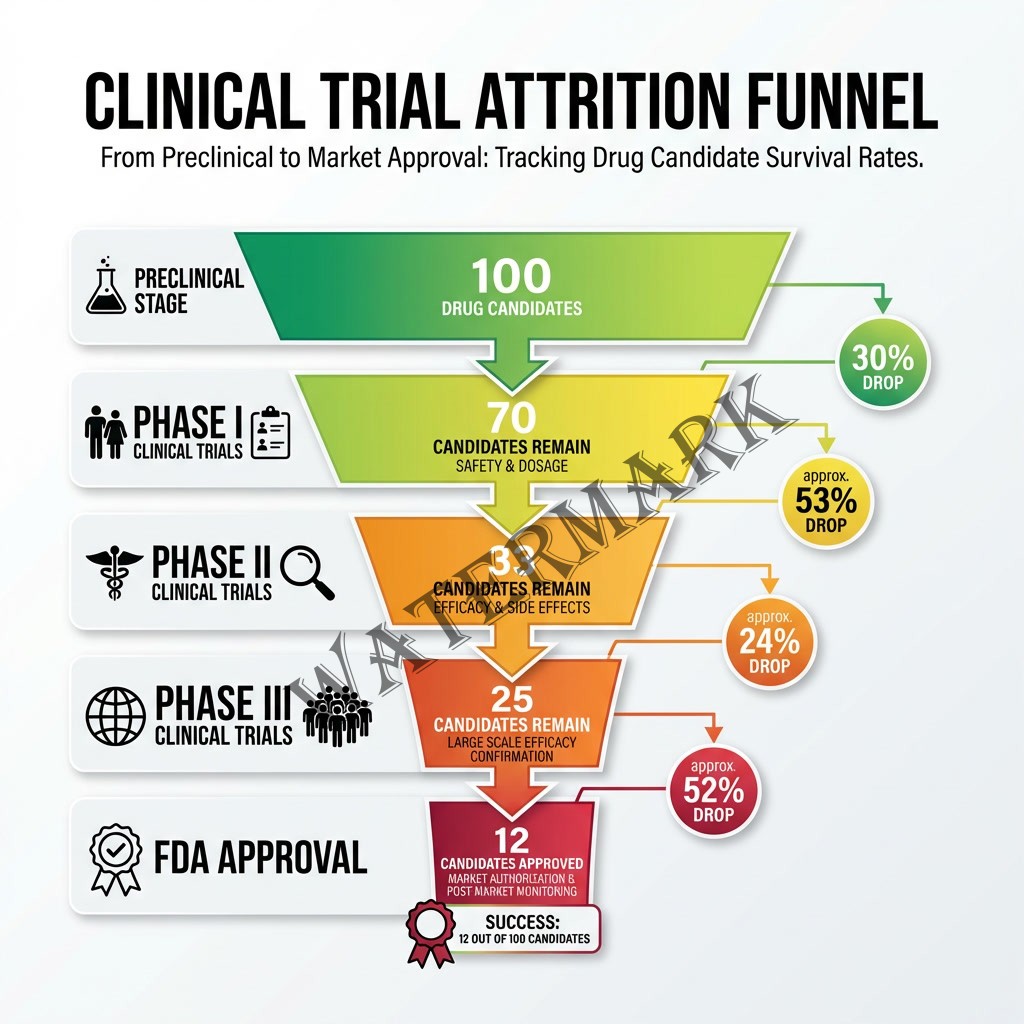

The attrition rate is genuinely horrifying. Only about 12% of drugs that enter Phase I clinical trials will ever receive FDA approval (DiMasi et al., 2016). That means for every 100 promising compounds that looked fantastic in the lab, 88 will fail somewhere along the decade-long journey. They’ll fail because they don’t work in humans the way they worked in mice. They’ll fail because they cause unexpected side effects. They’ll fail because they can’t be manufactured at scale, or because they don’t get absorbed properly, or because of a thousand other reasons that even the smartest scientists can’t always predict.

Here’s the dirty secret of drug discovery: for most of pharmaceutical history, we’ve been operating in what’s essentially a very expensive, very slow game of molecular roulette. Scientists would start with a biological target—maybe a protein that’s malfunctioning in cancer cells—and then screen hundreds of thousands or even millions of chemical compounds to find ones that interact with that target in useful ways. This process, called high-throughput screening, revolutionized drug discovery in the 1990s. But it’s still fundamentally about trial and error at massive scale.

“The central failure of drug development—an 85% failure rate in clinical trials—is not due to a lack of ambition, but a lack of predictive insight,” explains Derek Lowe, Director of Chemical Biology & Therapeutics at Novartis and author of the influential “In the Pipeline” blog (Lowe, 2025). Lowe, who has spent more than 27 years in pharmaceutical research, doesn’t mince words about the industry’s challenges. In a candid discussion at the 2025 Bio-IT World Conference, he pointed out the two biggest hurdles: “Better target selection and human toxicity prediction, the two things that kill most of the programs… are not yet within AI’s reach” (Lowe, 2025).

That “not yet” is doing a lot of work in that sentence, and we’ll come back to it. But first, let’s understand why drug discovery is so maddeningly difficult.

The human body is not a machine with standardized parts. It’s a staggeringly complex ecosystem of interacting systems, where changing one thing invariably affects seventeen others in ways that often defy prediction. A drug that perfectly blocks a cancer protein in a petri dish might also block a similar protein in your heart. A compound that works beautifully in mice might be metabolized completely differently in humans. A molecule that seems safe in 100 patients might cause a dangerous reaction in the 101st person who has a particular genetic variant you didn’t test for.

The problem isn’t lack of smart people—pharmaceutical companies employ some of the most brilliant chemists, biologists, and physicians on the planet. The problem is that biology is really, really complicated, and human intuition, no matter how well-trained, can only process so many variables at once.

Which brings us to the tantalizing possibility that artificial intelligence might be able to help.

Chapter Two: Enter the Machines—Silicon Chemists with Pattern Recognition Superpowers

In 2019, a relatively unknown biotech company called Insilico Medicine made an audacious claim: they had used artificial intelligence to identify a novel drug target and design a drug candidate to hit that target in just 46 days. Not years. Days.

The pharmaceutical industry’s collective reaction ranged from intense skepticism to cautious fascination. Because if this was real—if AI could genuinely compress years of work into weeks—then we were looking at a paradigm shift that would make the genomics revolution look quaint.

Alex Zhavoronkov, the founder and CEO of Insilico Medicine, is the kind of scientist who makes big bets. A physicist-turned-AI-researcher-turned-drug-developer, Zhavoronkov has been working at the intersection of artificial intelligence and medicine since before it was fashionable. “At Insilico we already have the most efficient drug discovery engine that can generate molecules with desired properties,” Zhavoronkov stated in a 2024 interview, “and we will be ready for the future when we can formulate a hypothesis using a PreciousGPT Life Model, generate a drug, and then test it in a clinical trial” (Zhavoronkov, 2024).

That might sound like techno-optimist hyperbole, but here’s the thing: Insilico Medicine actually delivered. In 2023, the company became the first to advance a fully AI-discovered and AI-designed drug—ISM001-055, a TNIK inhibitor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—into Phase II clinical trials with patients (Ren et al., 2025). That timeline from initial discovery to human trials? Eighteen months. In an industry where development typically takes a decade or more, this was the pharmaceutical equivalent of breaking the sound barrier.

And Insilico isn’t alone. By the end of 2024, over 75 AI-derived molecules had reached clinical stages, with the growth trajectory showing exponential acceleration (Dharmasivam et al., 2026). We’re seeing positive Phase IIa results, major pharmaceutical partnerships worth billions, and a fundamental rethinking of how drug discovery might work in the future.

So what exactly is AI doing that’s so revolutionary?

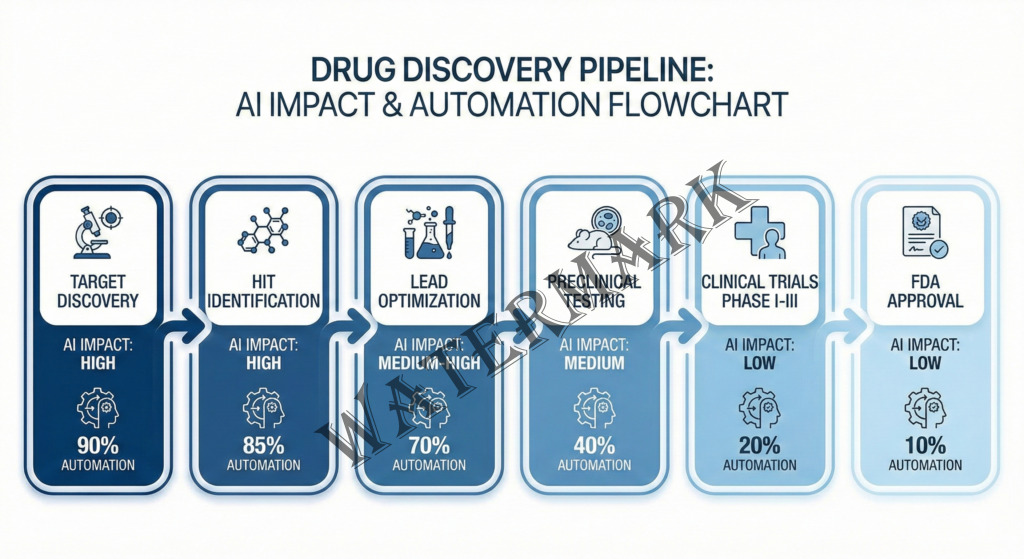

At its core, AI drug discovery leverages several interconnected capabilities that computers do better than humans. First, there’s pattern recognition at scale. Machine learning algorithms can analyze massive datasets—millions of scientific papers, decades of experimental results, entire databases of molecular structures—and identify patterns that would be invisible to human researchers. These systems can spot subtle relationships between chemical structures and biological activity that might take a human scientist years to notice, if they ever noticed them at all.

Second, there’s molecular generation. Using techniques called generative models (similar to the AI that creates images or text), systems can actually design new molecules with specific desired properties. Need a compound that binds strongly to a particular protein, crosses the blood-brain barrier, isn’t toxic to the liver, and can be manufactured at scale? The AI can generate thousands of candidate structures that theoretically meet those criteria—candidates that don’t exist anywhere in nature and that human chemists might never have dreamed up.

Third, there’s predictive modeling. Modern AI systems can predict, with increasing accuracy, how a molecule will behave: Will it bind to the target protein? How strongly? What about off-target effects? How will the body metabolize it? What’s the likelihood of toxic side effects? These predictions aren’t perfect—not by a long shot—but they’re getting better every year.

The AI drug discovery sector drew $3.3 billion in venture funding in 2024, with major deals including Generate:Biomedicines’ $1 billion partnership with Novartis and Isomorphic Labs’ $600 million expansion to integrate AlphaFold into drug design (Drug Discovery News, 2025). These aren’t small bets by cautious investors—these are massive commitments from some of the biggest names in both technology and pharmaceuticals.

But perhaps the most significant development came in November 2024, when Recursion Pharmaceuticals and Exscientia—two of the pioneering companies in AI drug discovery—merged in a $688 million deal (Recursion Pharmaceuticals, 2024). This wasn’t a big company acquiring a struggling startup; this was a consolidation of equals, bringing together Recursion’s expertise in biological exploration with Exscientia’s precision chemistry design platform. The merged entity now commands over 10 clinical programs, partnerships with major pharmaceutical companies potentially worth $20 billion in milestone payments, and—critically—an 18-month window in which they expect 10 clinical readouts that will either validate or devastate the AI drug discovery thesis.

“We believe the proposed combination is deeply complementary and aligned with our missions to industrialize drug discovery to deliver high quality medicines and lower prices for consumers,” said Chris Gibson, Ph.D., Co-Founder and CEO of Recursion, who continues as CEO of the combined company (Recursion Pharmaceuticals, 2024).

That phrase—”industrialize drug discovery”—is key. What these companies are attempting is nothing less than transforming pharmaceutical R&D from a artisanal craft practiced by highly trained specialists into a scalable, predictable, automated process. It’s the difference between hand-crafting furniture and running a modern manufacturing plant.

Chapter Three: The Reality Check—Why This Isn’t (Yet) the Miracle You’ve Been Sold

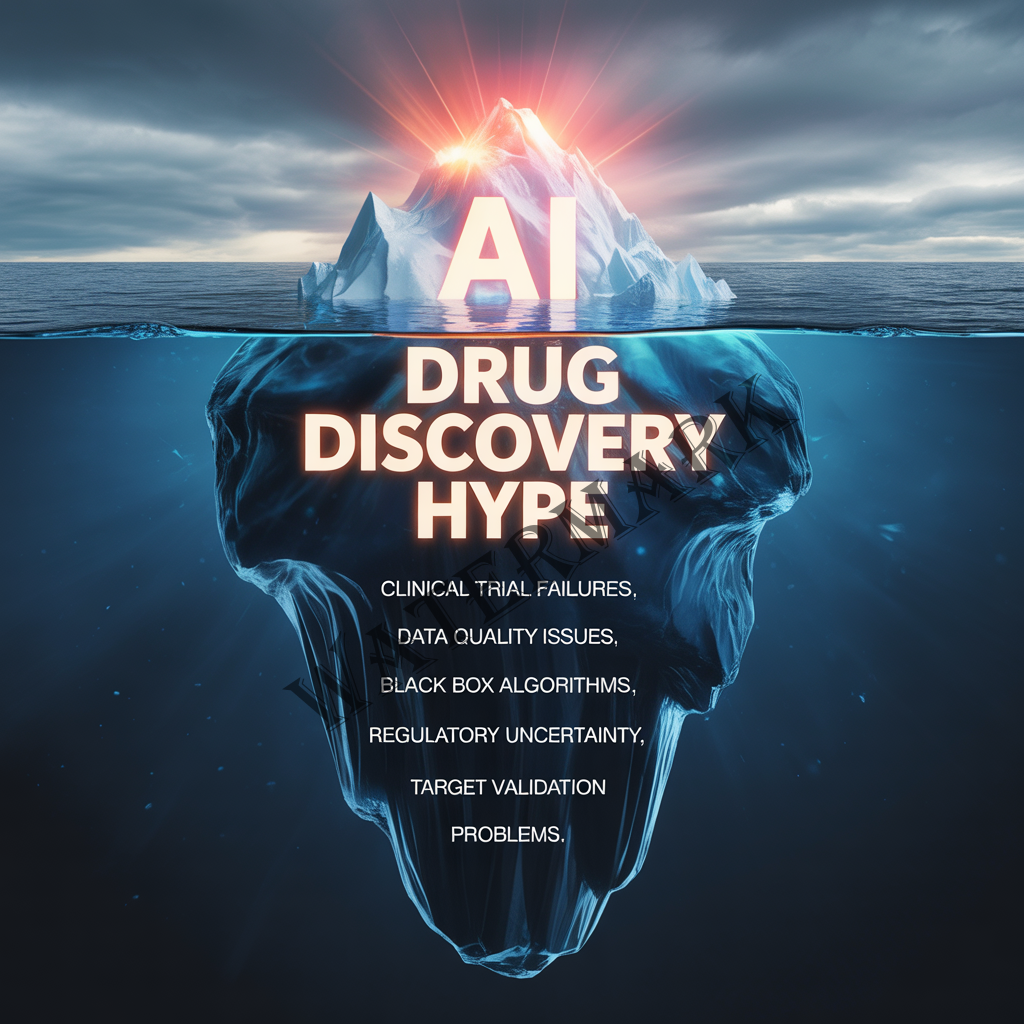

Now for the part that makes venture capitalists uncomfortable and scientists nod knowingly: AI drug discovery is genuinely promising, but it’s not magic, and the hype has gotten way ahead of the reality.

Let’s start with an inconvenient truth: as of February 2026, not a single AI-discovered drug has received full FDA approval and reached the market. Not one. Despite a decade of promises, billions in investment, and hundreds of press releases touting “breakthroughs,” we don’t yet have proof that AI can take a drug all the way from computer screen to pharmacy shelf.

The drugs currently in clinical trials are encouraging, absolutely. But here’s the thing about clinical trials: they’re specifically designed to fail most drugs. That 90% attrition rate we talked about earlier? It doesn’t magically disappear just because an AI designed the molecule. The biology is still complex. Humans are still unpredictable. And all the computational power in the world can’t change the fundamental reality that we don’t fully understand how the human body works.

Derek Lowe, who has become something of an industry conscience on AI hype, puts it bluntly: “I tell people I’m a short-term pessimist and a long-term optimist. I see no reason why these things can’t work—no mathematical, no logical, no biological or scientific reason why these things can’t work. It’s just that it’s going to be very hard to get them to work” (Lowe, 2025).

He’s particularly skeptical of the “AI will speed everything up” narrative that pervades the space. “Lowering the cost of the preclinical stages by 20% or making them 20% faster (which to a certain degree are the same thing) does indeed save you money,” Lowe wrote in his influential blog post “AI and Drug Discovery: Attacking the Right Problems.” “But while those would be nice (and remember, we aren’t there yet), the real problem is having drug candidates fail in the clinic. All that other stuff is a roundoff error compared to the clinical failure rate” (Lowe, 2021).

This is crucial to understand. AI might excel at the early stages—identifying targets, designing molecules, predicting binding affinity. But the expensive, time-consuming, high-failure parts of drug development are the clinical trials themselves. And AI can’t run clinical trials faster. You still need to recruit patients, administer the drug, wait to see if it works, monitor for side effects over months or years. That part is fundamentally bound by human biology and safety regulations, and no amount of computational power can accelerate it.

Then there’s the data quality problem. AI systems are only as good as the data they’re trained on. And here’s an uncomfortable secret about pharmaceutical data: much of it is messy, incomplete, or collected under inconsistent conditions. Published studies have a well-known bias toward positive results. Negative data often never sees the light of day. And the data that does exist may not capture the kind of subtle, context-dependent biological reality that determines whether a drug works in humans.

“Garbage in, garbage out” isn’t just a catchy phrase—it’s a fundamental limitation. If your AI is trained on incomplete or biased data, it will make incomplete or biased predictions. And unlike a human scientist who might notice something feels off, an AI will confidently extrapolate from flawed training data and generate impressively wrong answers.

There’s also the black box problem. Many of the most powerful AI systems—particularly deep learning neural networks—are essentially inscrutable. They can tell you that Molecule X is likely to bind strongly to Protein Y, but they can’t always explain why in terms that a human chemist can understand and verify. This lack of interpretability isn’t just philosophically troubling; it has practical consequences. When a drug candidate fails in clinical trials, you want to understand why so you can improve your next attempt. If an AI designed the molecule and can’t explain its reasoning, you’re back to square one.

And then there’s the uncomfortable question of whether AI is actually discovering anything fundamentally new, or whether it’s just very efficiently recombining existing knowledge. Critics point out that AI systems are trained on historical data—drug compounds that have been tried before, proteins whose structures are known, experiments that have already been run. Can a system trained on the past truly generate radically novel insights? Or is it just a very sophisticated pattern-matching engine that will always be bounded by human knowledge?

The optimists argue that AI can find non-obvious combinations and connections that humans miss. The skeptics worry that we’re building very expensive autocomplete for chemistry. The honest answer is: we don’t know yet. We won’t know until these AI-designed drugs make it through clinical trials and we can evaluate whether they represent genuine innovation or just efficient recapitulation of existing pharmacological principles.

Chapter Four: The Philosophical Dilemma—Who Owns the Future of Medicine?

Here’s where things get really interesting—and a bit uncomfortable. Because AI drug discovery isn’t just a technical question; it’s a profound ethical and economic one that will shape who has access to life-saving medications for generations to come.

Consider this scenario: An AI system designs a breakthrough drug for a rare disease. The AI was trained on decades of publicly funded research, genomic databases built with patient data, and clinical trial results published in academic journals. But the company that owns the AI platform patents the resulting drug and charges $500,000 per year for treatment.

Who, exactly, should own that drug? The company that built the AI? The patients whose data trained it? The taxpayers who funded the underlying research? And more fundamentally: if AI can dramatically reduce the cost of drug discovery—compressing that $2.6 billion price tag down to, say, $200 million—should we expect drug prices to fall accordingly?

Spoiler alert: don’t hold your breath.

The pharmaceutical industry’s argument for high drug prices has always rested on the enormous risk and cost of R&D. If AI genuinely reduces both risk and cost, that argument becomes significantly weaker. But companies will counter that they still face massive expenses in clinical trials, regulatory approval, and manufacturing scale-up. They’ll point to the need to recoup costs from failed programs. And they’ll argue that R&D efficiency should increase innovation, not lower prices.

Alex Zhavoronkov has been remarkably transparent about Insilico’s goal to position itself as “a factory of drugs” (Regalado, 2024). That industrial metaphor is revealing. Factories are about efficiency, scale, and output—not necessarily about accessibility or affordability. “Our job is to be a factory of drugs,” Zhavoronkov told MIT Technology Review, emphasizing the company’s focus on productivity rather than pricing (Regalado, 2024).

But efficiency without equity creates troubling scenarios. Imagine a future where AI-powered drug discovery becomes so dominant that only companies with massive AI infrastructure and proprietary datasets can compete. These companies could identify and patent so many potential drug candidates—even ones they never intend to develop—that they effectively lock competitors out of entire areas of drug space. The result would be unprecedented concentration of pharmaceutical power in a handful of AI giants.

This concern isn’t hypothetical. In 2024, global venture funding for AI drug discovery reached $3.3 billion, with deals like the $1 billion partnership between Generate:Biomedicines and Novartis demonstrating how AI capability is becoming a prerequisite for competitiveness (Drug Discovery News, 2025). Smaller biotech companies without deep AI expertise or massive datasets may find themselves increasingly unable to compete. Academic research groups certainly can’t match the computational resources of well-funded AI drug companies.

There’s also the question of data colonialism. Much of the biological and clinical data used to train AI systems comes from Western populations, particularly from patients in the United States and Europe. If AI drug discovery is optimized on this data, will it work as well for populations that were underrepresented in training? We already know that many medications have different efficacy and side effect profiles across different ethnic groups. AI trained primarily on data from one population may inadvertently design drugs that work best for that population, widening existing health disparities rather than closing them.

“The North-South divide in access to AI technology” is already a recognized challenge in AI drug discovery (Dharmasivam et al., 2026). Countries without advanced AI infrastructure or access to large-scale computational resources may find themselves shut out of the AI revolution in pharmaceuticals, forced to rely on licensing deals with tech-rich nations and companies. This could entrench existing global health inequalities at precisely the moment when we have the technological capability to dramatically expand access to new medicines.

And then there’s the ultimate philosophical question that keeps bioethicists up at night: If an AI designs a drug, who’s responsible when something goes wrong?

Traditional drug development has clear lines of accountability. Human scientists make decisions, document their reasoning, and take responsibility for the outcomes. But when an AI system recommends a particular molecular structure based on inscrutable pattern recognition across millions of data points, who bears responsibility if that drug causes unexpected harm? The company that deployed the AI? The engineers who built it? The executives who approved its use?

This isn’t abstract philosophy—it’s a practical regulatory and legal nightmare that we haven’t begun to solve. In January 2025, the FDA released draft guidance on AI in drug development, acknowledging the technology’s potential while emphasizing the need for transparency, validation, and human oversight (FDA, 2025). But that guidance stops well short of answering the deeper questions about liability, accountability, and the appropriate role of algorithmic decision-making in life-or-death medical contexts.

These aren’t questions with easy answers. They’re the kind of thorny, multifaceted dilemmas that require ongoing dialogue between scientists, ethicists, policymakers, patients, and the public. What’s clear is that we can’t simply let market forces and technical capability determine how AI drug discovery unfolds. The stakes—quite literally life and death for millions of patients—are too high.

Chapter Five: What’s Actually Working—Real Results from the Frontier

Enough doom-mongering. Let’s talk about what’s genuinely impressive and working right now in AI drug discovery, because amidst all the hype and all the skepticism, there are legitimate achievements worth celebrating.

First, the successes in target discovery and validation. Researchers at Oxford Drug Discovery Institute used AI to evaluate 54 immune-related genes as potential Alzheimer’s disease targets—a process that once took weeks, now completed in days (Drug Discovery News, 2025). This isn’t just about speed; it’s about breadth of exploration. AI can evaluate hypotheses that human researchers might never think to test, simply because there are too many possibilities to explore manually.

In antibody design and protein engineering, AI has made remarkable strides. The collaboration between AstraZeneca and the University of Sheffield developed MapDiff, an innovative AI framework for inverse protein folding that “outperforms existing methods and represents a significant leap forward in our ability to design novel therapeutic proteins with specific functions” (AstraZeneca, 2025). Similarly, their partnership with Cambridge University created Edge Set Attention (ESA) for predicting key molecular properties of potential medicines, significantly outperforming existing methods.

In drug repurposing, AI is finding new uses for existing medications at unprecedented speed. Startup companies like Ignota Labs are using AI to mine public and proprietary datasets for repurposing opportunities, “aiming to reduce repurposing timelines to less than two years and costs to under $1 million” (Drug Discovery News, 2025). When you can find a new use for an already-approved drug, you skip huge amounts of safety testing—the drug’s already been proven safe in humans. This dramatically reduces both risk and timeline.

Perhaps most impressive are the full-stack AI platforms that integrate multiple stages of drug discovery. Insilico Medicine’s platform combines PandaOmics for target discovery, Chemistry42 for molecular design, and inClinico for predicting clinical trial outcomes. This end-to-end approach led to their lead compound progressing from initial concept to preclinical candidate in approximately 13 months—a timeline that Zhavoronkov describes as “realistic” given their global network of over 40 contract research organizations running experiments in parallel (Zhavoronkov, 2025).

The Recursion-Exscientia merger creates a similarly comprehensive platform, combining Recursion’s scaled biology exploration (running up to millions of wet lab experiments weekly) with Exscientia’s precision chemistry and automated synthesis capabilities (Recursion Pharmaceuticals, 2024). Over the next 18 months, this combined entity will produce approximately 10 clinical readouts—real data from human trials that will test whether AI-designed drugs actually work.

And then there’s the growing body of pharmaceutical partnerships that suggests major drug companies take this technology seriously. AstraZeneca has 27 major AI collaborations, Merck has 22, and Sanofi, Roche, and other pharma giants have committed hundreds of millions to AI drug discovery partnerships (AION Labs, 2025). These aren’t vanity projects or PR stunts—these are strategic investments by companies betting their future on the technology.

The FDA’s engagement is another positive signal. In January 2025, the agency released draft guidance on AI in drug development, building on experience reviewing over 500 AI-related regulatory submissions since 2016 (FDA, 2025). The guidance encourages early engagement between AI developers and regulators, acknowledging that the technology requires new regulatory frameworks while maintaining rigorous standards for safety and effectiveness.

Real-world clinical progress is perhaps the most exciting development. Insilico’s ISM001-055 showed positive Phase IIa results in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Ren et al., 2025). Zasocitinib (TAK-279), a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor designed using Schrödinger’s physics-enabled AI platform, advanced into Phase III trials (Dharmasivam et al., 2026). These aren’t just compounds entering trials—these are drugs showing actual efficacy signals in human patients.

Under the leadership of Nobel Laureate Dr. Stanley Prusiner, a team at UCSF confronting Parkinson’s therapy development projected in 2024 that a promising treatment wouldn’t reach clinical trials until 2031 using traditional approaches. After partnering with SandboxAQ’s large quantitative models (LQMs), they dramatically accelerated their timeline (World Economic Forum, 2025). While the ultimate success remains to be seen, the ability to compress development timelines even partially represents genuine progress.

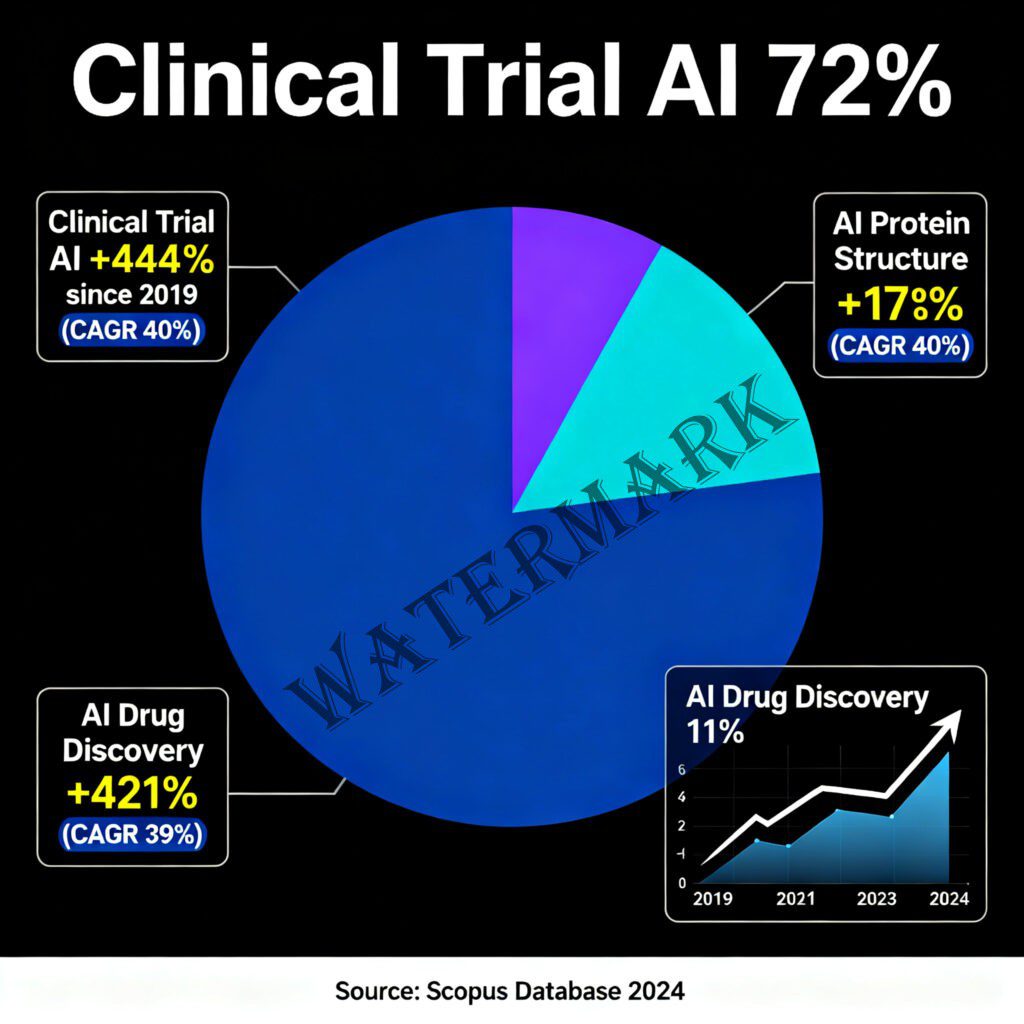

The publication record also reflects growing sophistication. According to Scopus data, clinical trial AI publications represent 72% of projected 2024 papers (7,442 publications), with AI drug discovery at 11% (1,147 publications) showing a 421% increase since 2019 (Drug Discovery News, 2024). This isn’t hype—this is serious scientific work being published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at major conferences.

Chapter Six: The Road Ahead—2026 and the Moment of Truth

We’re standing at an inflection point. The next 18-24 months will likely determine whether AI drug discovery becomes a transformative force in medicine or a cautionary tale about overhyped technology.

Here’s why this window matters so much: All those AI-designed drugs currently in clinical trials? They’re about to produce data. Real, actual, statistically significant (or not) results from human patients. When Recursion talks about 10 clinical readouts over the next 18 months, they’re putting their credibility—and their stock price—on the line. When Insilico advances multiple compounds through Phase II trials, we’ll finally see whether computational predictions translate to clinical efficacy.

If these drugs work—if they demonstrate safety and efficacy comparable to or better than traditionally discovered drugs—then the pharmaceutical industry will have no choice but to fully embrace AI. The competitive advantage will be too significant to ignore. We’ll see a massive acceleration in AI adoption, with every major pharmaceutical company racing to build or acquire AI drug discovery capabilities.

But if they fail—if the clinical data shows that AI-designed drugs aren’t substantially better than traditionally designed ones, or worse, if they have unexpected safety problems—then we’ll see a sharp correction. Investment will dry up, the hype will deflate, and AI drug discovery will retreat to a more modest supporting role in traditional pharmaceutical R&D.

Derek Lowe’s perspective on this is characteristically balanced: “AI is getting better all the time, and we’re not,” he noted, acknowledging both the technology’s trajectory and human limitations (Lowe, 2022). His view—that he’s a “short-term pessimist but long-term optimist”—captures the reality that genuine transformation takes longer than press releases suggest, but may ultimately be more profound than skeptics expect.

The 2025 FDA guidance on AI in drug development signals that regulators are preparing for AI-powered drugs to become routine. The guidance focuses on transparency, explainability, validation, and human oversight—suggesting that regulatory approval of AI-designed drugs is coming, but will require meeting high standards for both the drugs themselves and the AI systems that created them (FDA, 2025).

From a business perspective, the consolidation in the AI drug discovery space—exemplified by the Recursion-Exscientia merger—suggests a maturing market. The era of dozens of small startups each claiming to revolutionize drug discovery is giving way to fewer, better-capitalized companies with comprehensive platforms and actual clinical assets. This consolidation may be uncomfortable for some stakeholders, but it’s often a sign that a technology is moving from hype to real-world application.

Looking further ahead, the most exciting possibilities involve integration rather than replacement. The future of drug discovery likely isn’t “AI versus humans” but rather “AI-augmented human scientists” who use computational tools to explore chemical and biological space more efficiently while bringing human intuition, creativity, and judgment to the process.

Imagine a medicinal chemist who can test thousands of hypotheses virtually before ever picking up a pipette. Imagine a clinical researcher who can predict which patients are most likely to respond to a new treatment before enrolling them in trials. Imagine regulatory reviewers who can simulate a drug’s behavior in diverse populations to identify potential safety issues before they emerge in the real world.

This isn’t replacing scientists—it’s giving them superpowers.

There’s also the possibility that AI might help democratize drug discovery. OpenFold and other open-source efforts are attempting to create freely available tools that could enable smaller labs and researchers in resource-limited settings to compete with well-funded pharmaceutical giants. Whether this vision of democratization can coexist with the commercial realities of drug development remains an open question, but the potential is tantalizing.

Conclusion: The Verdict? Ask Again in 18 Months

So where does this leave us?

AI drug discovery is real. It’s producing actual results—faster target identification, novel molecular designs, drugs in clinical trials that were created in unprecedented timelines. Companies are investing billions, major pharmaceutical partnerships are being formed, and the FDA is preparing regulatory frameworks to accommodate AI-designed therapeutics.

But AI drug discovery is also overhyped. It hasn’t yet proven it can deliver approved, marketed drugs. The most challenging parts of drug development—clinical validation, safety monitoring, regulatory approval—aren’t amenable to computational shortcuts. And the early failures and unexpected complications haven’t happened yet because we’re still in the early days.

The truth sits somewhere in the uncomfortable middle ground between revolutionary promise and practical reality. What we’re witnessing is genuine technological progress that will likely transform drug discovery, but more slowly and with more complications than the most optimistic forecasts suggest.

Alex Zhavoronkov’s vision of a “factory of drugs” producing therapeutic candidates at industrial scale represents one possible future (Regalado, 2024). But Derek Lowe’s cautionary wisdom—that this is “a really, really, really hard problem” that will take longer to solve than anyone wants to admit—represents the more likely path (Lowe, 2025).

The next 18 months will be critical. The wave of clinical readouts from AI-designed drugs will tell us whether computational predictions translate to human biology. The growing number of pharmaceutical partnerships will reveal whether major drug companies see AI as transformative or merely incremental. And the regulatory frameworks being developed now will determine how AI drug discovery integrates into the heavily regulated world of pharmaceutical development.

For patients—the people who will ultimately benefit or not from these advances—the message is one of cautious optimism. Don’t expect miracle cures tomorrow. Don’t believe every press release about “revolutionary” AI-designed drugs. But also don’t dismiss the genuine progress being made by serious scientists using powerful new tools to tackle one of humanity’s hardest problems.

Medicine has always advanced through a combination of brilliant insights, painstaking labor, fortunate accidents, and incremental improvements. AI drug discovery is adding something new to that mix: unprecedented computational power applied to biological complexity. Whether that addition proves transformative or merely useful remains to be seen.

But one thing is certain: we’re living through a genuinely interesting moment in pharmaceutical history. The marriage of silicon and biology is producing something new—not quite what the hype promised, not quite what the skeptics feared, but something real and evolving and worth paying attention to.

The revolution will not be pipetted by hand. But it also won’t be as simple as letting the machines take over. Instead, we’re stumbling—sometimes brilliantly, sometimes clumsily—toward a hybrid future where human intuition and artificial intelligence collaborate to discover drugs faster, cheaper, and maybe even better than either could alone.

And that future? Well, we’ll know a lot more about it by this time next year.

References

- AstraZeneca. (2025, October 3). AI drug discovery: MapDiff & edge set attention breakthroughs. https://www.astrazeneca.com/content/astraz/what-science-can-do/topics/data-science-ai/mapdiff-edge-set-attention-ai-protein-design-breakthroughs.html

- AION Labs. (2025, August 20). The AI revolution in pharma – Will 2025 be the breakthrough year? https://aionlabs.com/the-ai-revolution-in-pharma-will-2025-be-the-breakthrough-year/

- Dharmasivam, M., Kaya, B., Akinware, A., Azad, M. G., & Richardson, D. R. (2026). Leading artificial intelligence–driven drug discovery platforms: 2025 landscape and global outlook. Pharmacological Reviews, 78(1), 100103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031699725075118

- DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33.

- Drug Discovery News. (2024, November 25). 2024: The year AI drug discovery and protein structure prediction took center stage—2025 set to amplify growth. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/2024-the-year-ai-drug-discovery-and-protein-structure-prediction-took-center-stage-2025-set-to-amplify-growth/

- Drug Discovery News. (2025, October 2). How AI is transforming drug discovery. https://www.drugdiscoverynews.com/ai-is-transforming-drug-discovery-16706

- Food and Drug Administration. (2025). Using artificial intelligence and machine learning in the development of drug and biological products: Draft guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/using-artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-development-drug-and-biological-products

- Lowe, D. (2021, April 19). AI and drug discovery: Attacking the right problems. Science Translational Medicine. https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/ai-and-drug-discovery-attacking-right-problems

- Lowe, D. (2022, June 16). Sold on the new machine. Chemical & Engineering News, 100(7). https://cen.acs.org/business/informatics/Sold-new-machine/100/i7

- Lowe, D. (2025, April 15). Derek Lowe on AI in drug discovery: Between hype and hope. Bio-IT World. https://www.bio-itworld.com/news/2025/04/15/derek-lowe-on-ai-in-drug-discovery-between-hype-and-hope

- Recursion Pharmaceuticals. (2024, August 8). Recursion and Exscientia enter definitive agreement to create a global technology-enabled drug discovery leader with end-to-end capabilities [Press release]. https://ir.recursion.com/news-releases/news-release-details/recursion-and-exscientia-enter-definitive-agreement-create

- Regalado, A. (2024, March 20). An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/03/20/1089939/a-wave-of-drugs-dreamed-up-by-ai-is-on-its-way/

- Ren, F., Aliper, A., Chen, J., Zhao, H., Rao, S., Kuppe, C., Ozerov, I. V., Zhang, M., Witte, K., Kruse, C., Aladinskiy, V., Veviorskiy, A., Ivanenkov, Y., Zhavoronkov, A., & Costa, I. G. (2025). A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models. Nature Biotechnology, 43, 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02143-0

- Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. (2014). Cost to develop and win marketing approval for a new drug is $2.6 billion. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cost-to-develop-and-win-marketing-approval-for-a-new-drug-is-26-billion-300214114.html

- World Economic Forum. (2025, December). Using large quantitative models and AI in drug discovery. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/12/large-quantitative-models-how-ai-is-accelerating-drug-discovery/

- Zhavoronkov, A. (2024, August 28). Q&A: Alex Zhavoronkov on cognitive enhancement, anti-aging, and AI drug development. Petrie-Flom Center, Harvard Law School. https://petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2024/08/28/qa-alex-zhavoronkov-on-cognitive-enhancement-anti-aging-and-ai-drug-development/

- Zhavoronkov, A. (2025, April 17). Insilico’s Alex Zhavoronkov highlights generative AI’s impact on drug discovery and aging research. Bio-IT World. https://www.bio-itworld.com/news/2025/04/17/insilico-s-alex-zhavoronkov-highlights-generative-ai’s-impact-on-drug-discovery-and-aging-research

Additional Reading

- Fleming, N. (2018). How artificial intelligence is changing drug discovery. Nature, 557(7707), S55-S57. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05267-x

- Paul, D., Sanap, G., Shenoy, S., Kalyane, D., Kalia, K., & Tekade, R. K. (2021). Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discovery Today, 26(1), 80-93. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359644620304220

- Mak, K. K., & Pichika, M. R. (2019). Artificial intelligence in drug development: Present status and future prospects. Drug Discovery Today, 24(3), 773-780. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359644618303659

- Vamathevan, J., Clark, D., Czodrowski, P., Dunham, I., Ferran, E., Lee, G., Li, B., Madabhushi, A., Shah, P., Spitzer, M., & Zhao, S. (2019). Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18(6), 463-477. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-019-0024-5

- Zhavoronkov, A., Ivanenkov, Y. A., Aliper, A., Veselov, M. S., Aladinskiy, V. A., Aladinskaya, A. V., Terentiev, V. A., Polykovskiy, D. A., Kuznetsov, M. D., Asadulaev, A., Volkov, Y., Zholus, A., Shayakhmetov, R. R., Zhebrak, A., Minaeva, L. I., Zagribelnyy, B. A., Lee, L. H., Soll, R., Madge, D., … Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2019). Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent DDR1 kinase inhibitors. Nature Biotechnology, 37(9), 1038-1040. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-019-0224-x

Additional Resources

- Insilico Medicine – Clinical-stage AI drug discovery company pioneering generative AI for drug design

https://insilico.com - Recursion Pharmaceuticals – Technology-enabled drug discovery platform combining biology and AI

https://www.recursion.com - FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) – Regulatory guidance and information on AI in drug development

https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder - Nature Reviews Drug Discovery – Leading journal covering drug discovery, including AI applications

https://www.nature.com/nrd - “In the Pipeline” by Derek Lowe – Industry-leading blog on drug discovery and pharmaceutical R&D

https://www.science.org/blogs/pipeline

Leave a Reply