How a 1973 British report by mathematician James Lighthill devastated

AI funding and sent the field into a decade-long ice age we’re still learning from.

Author’s Note

This article is a substantially expanded deep dive building on our earlier post,

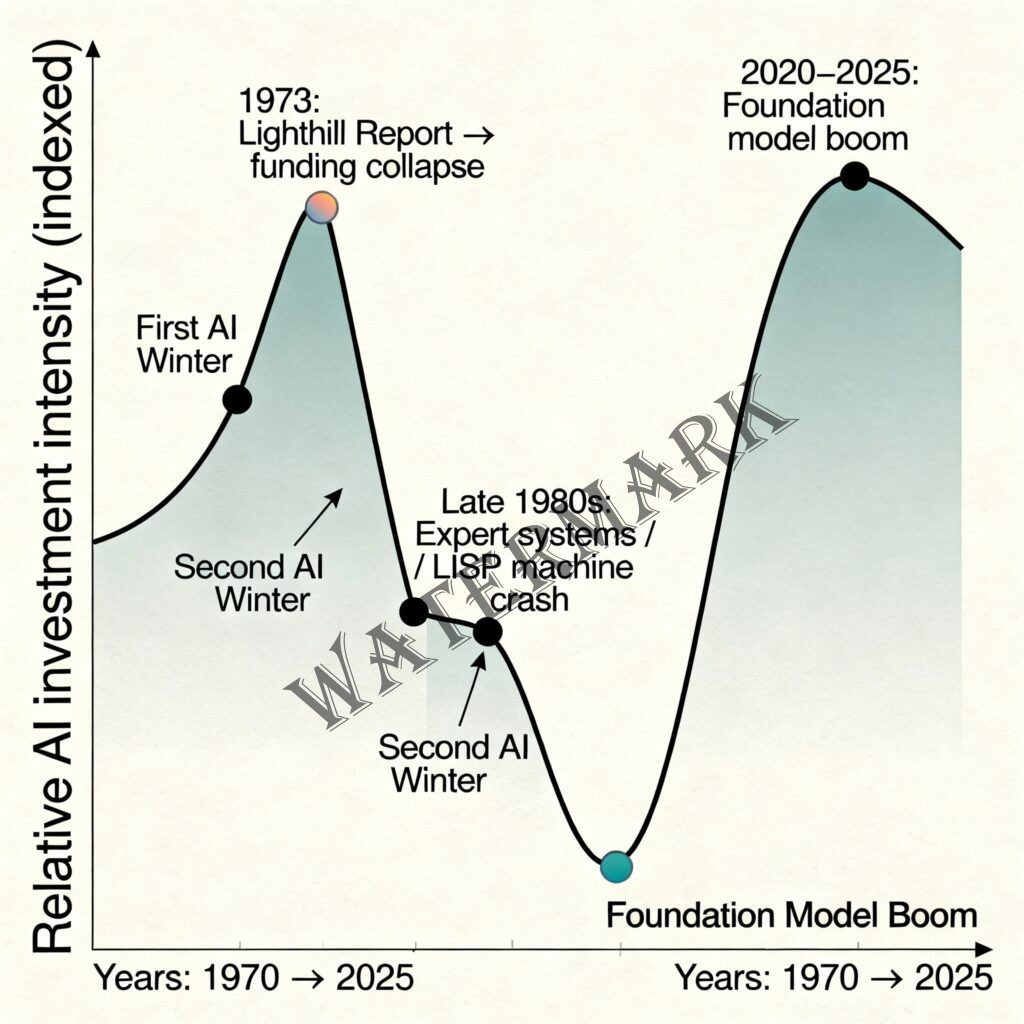

“A Chilly History: How a 1973 Report Caused the Original AI Winter.”While the original article introduced the Lighthill Report and its immediate impact on artificial intelligence funding, this version goes much further. It examines the full historical, technical, philosophical, and economic context—tracing clear lines from the 1973 critique through both AI winters and into today’s foundation-model boom.

New material in this expanded analysis includes primary-source interpretation, funding and investment data, technical limitations such as combinatorial explosion and hallucinations, historical failure case studies, and modern parallels that could not be explored in a shorter format.

The report that froze a revolution

In the summer of 1973, a single report—written by a man who had never worked a day in artificial intelligence—brought the field’s golden age crashing down. Sir James Lighthill, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge (the same chair once held by Isaac Newton), delivered a 49-page verdict that would reshape computing history: AI researchers had massively overpromised and spectacularly underdelivered.

The consequences were swift and brutal. Within months, the British government gutted AI funding at all but two universities. American funders followed suit. Research programs collapsed. Careers ended. The field entered what scientists would later call the “AI Winter”—a period of frozen budgets, abandoned projects, and shattered dreams that lasted nearly a decade.

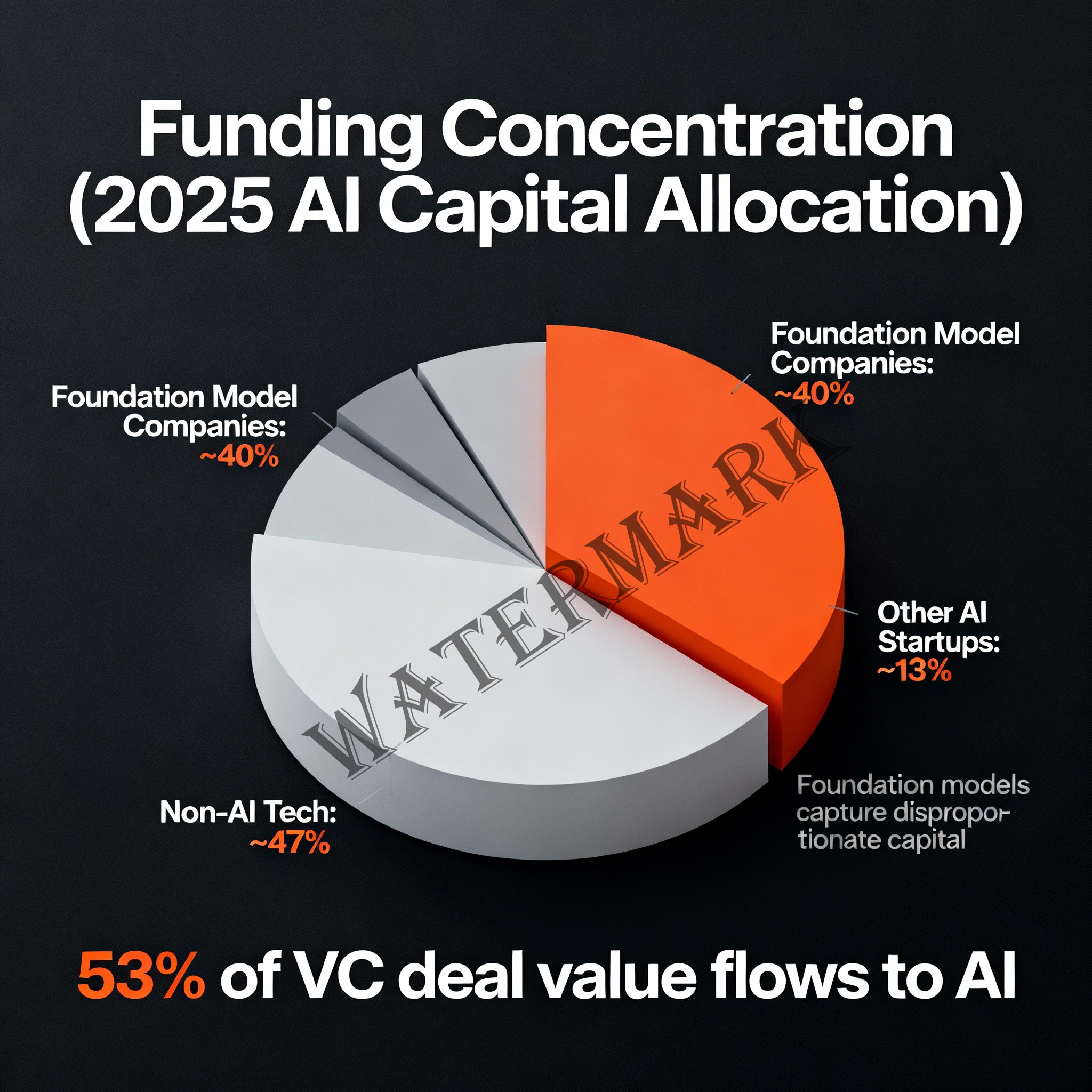

Why does this matter now? Because we may be living through a remarkably similar moment. As of 2025, AI-related companies have captured 53% of global venture capital deal value, up from just 32% in 2024. A staggering $202.3 billion has poured into the AI sector in 2025 alone—a 75% increase from 2024’s $114 billion. OpenAI alone raised $40 billion in March 2025, the largest single venture round in history.

Yet warning signs abound. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, admitted at a press dinner in August 2024: “Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? My opinion is yes. Is AI the most important thing to happen in a very long time? My opinion is also yes.”

That tension—between genuine breakthrough and dangerous hype—is precisely what Lighthill identified fifty years ago. And his report offers something invaluable: a detailed autopsy of how an entire field can lose its way.

The man who wasn’t supposed to understand AI

James Lighthill seemed an unlikely candidate to reshape artificial intelligence’s destiny. Born in Paris in 1924, he was a fluid dynamicist—a pioneer who literally founded the field of aeroacoustics and developed Lighthill’s eighth power law for jet noise. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society at just 29, knighted in 1971, and held positions at Manchester, the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and Imperial College London before assuming the Lucasian Professorship in 1969.

The Science Research Council deliberately chose an outsider. According to the report’s preface, they wanted “an independent report by someone outside the AI field but with substantial general experience of research work in multidisciplinary fields including fields with mathematical engineering and biological aspects.”

Translation: they wanted someone who wouldn’t be dazzled by the hype.

Lighthill spent two months in 1972 reviewing the literature, corresponding with researchers, and visiting laboratories. What he found disturbed him profoundly. The promises had been extraordinary—machines that could think, reason, understand language, and solve problems with human-level intelligence. The reality was far more modest.

“In no part of the field have the discoveries made so far produced the major impact that was then promised,” Lighthill wrote. The chess programs could only play at “experienced amateur” level. Robot research in eye-hand coordination and common-sense problem-solving was “entirely disappointing.” The celebrated SHRDLU natural language system—which could manipulate virtual blocks through English commands—worked only in what Lighthill dismissively called a “playpen world.”

Three categories and one devastating critique

Lighthill’s framework divided AI research into three categories that revealed his surgical thinking:

Category A: Advanced Automation—practical applications like optical character recognition, missile guidance, and automated manufacturing. Lighthill endorsed this work. It had clear objectives, measurable outcomes, and genuine utility.

Category C: Computer-based Central Nervous System Research—using computers to model how brains and minds work. Lighthill saw value here too, viewing it as legitimate neuroscience and psychology research that happened to use computational tools.

But Category B: Building Robots—the ambitious pursuit of general-purpose, human-level intelligence—received Lighthill’s harshest criticism. This was the glamorous center of AI research, the work that promised thinking machines. And Lighthill called it a failure.

His core technical objection was combinatorial explosion. The problem is devastatingly simple to understand. In chess, there are roughly 20 possible moves per turn. Looking ahead 6 moves takes about one second at a million calculations per second. Looking ahead 12 moves takes 11 days. Looking ahead 18 moves? Roughly 32,000 years.

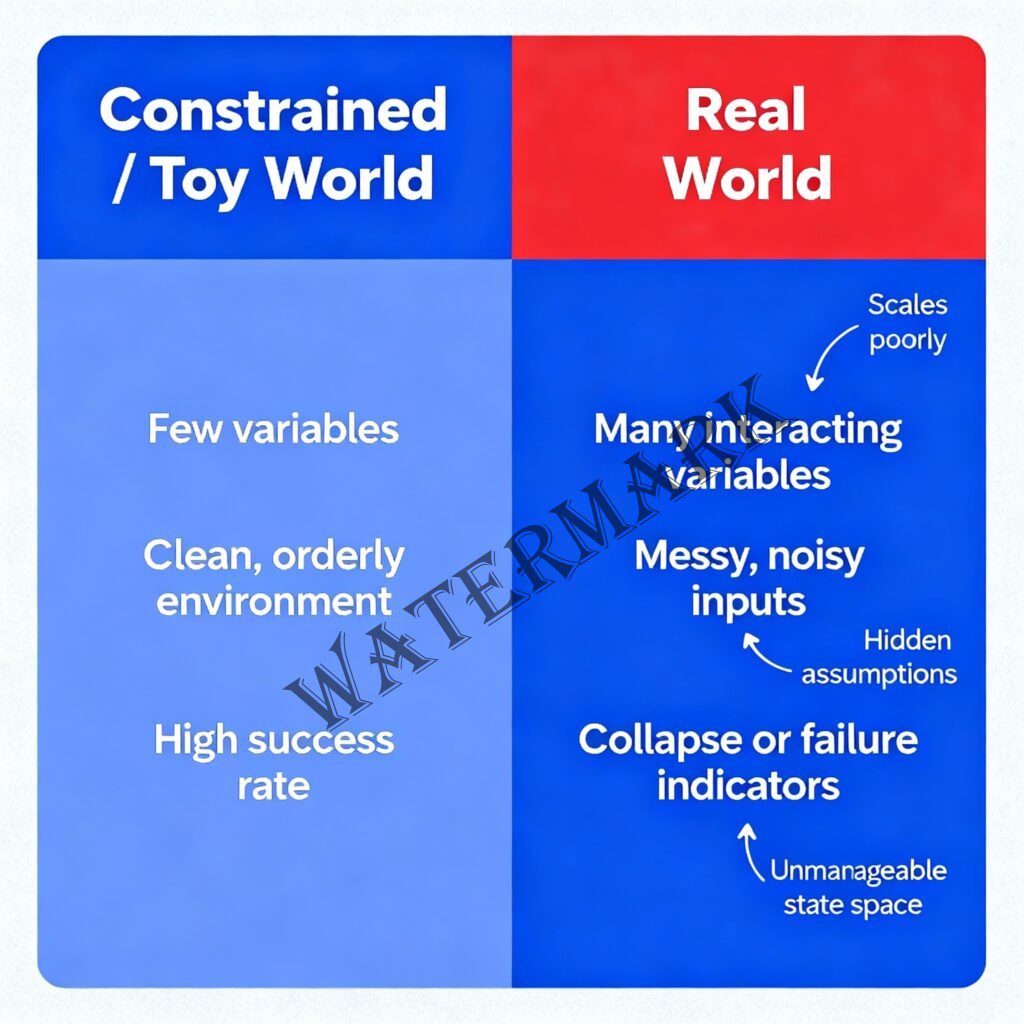

AI techniques that worked brilliantly on small, constrained “toy problems” couldn’t scale to real-world complexity. The number of possible states, paths, and outcomes exploded exponentially, overwhelming any conceivable computational approach. This wasn’t a temporary engineering limitation—it was a fundamental mathematical wall.

Lighthill predicted that within 25 years, Category A would become applied technology, Category C would integrate with psychology and neurobiology, and Category B—the grand dream of human-level artificial intelligence—would be abandoned entirely.

The BBC debate that sealed AI’s fate

On May 9, 1973, the Royal Institution in London hosted an intellectual spectacle. Lighthill would defend his report against three of the field’s most brilliant minds: Donald Michie, Professor of Machine Intelligence at Edinburgh; John McCarthy, the Stanford pioneer who had coined the very term “artificial intelligence”; and neuropsychologist Richard Gregory.

The debate, broadcast on BBC Television in June 1973 as part of the “Controversy” series, centered on a provocative proposition: “The general purpose robot is a mirage.”

McCarthy and Michie arrived with demonstrations, including footage of Shakey, the Stanford Research Institute robot that could navigate rooms and push objects. Michie cited David Levy’s famous 1968 bet—£1,000 that no computer would beat him at chess within a decade (Levy won the bet in 1978, but would later lose to Deep Thought in 1989).

Lighthill was unimpressed. The demonstrations, he argued, showed systems operating in “playpen worlds” of limited complexity. The moment you introduced the messiness of reality—unpredictable lighting, ambiguous instructions, unexpected obstacles—these systems crumbled.

The debate crystallized a fundamental disagreement that persists today: Can intelligence be achieved through better algorithms and more computation, or does it require something fundamentally different—perhaps embodiment, perhaps biological architecture, perhaps concepts we haven’t yet imagined?

When the funding froze

The report’s impact was immediate and devastating. It “formed the basis for the decision by the British government to end support for AI research in most British universities,” according to historical accounts. Funding continued at only two institutions—Edinburgh and Sussex—while programs elsewhere were dismantled.

The chill spread across the Atlantic. The 1969 Mansfield Amendment had already required DARPA to fund “mission-oriented direct research, rather than basic undirected research.” By 1974, AI project funding became, in the words of the era, “hard to find.” Speech understanding research at Carnegie Mellon University faced harsh new evaluation criteria. Hans Moravec, who would become a leading roboticist, described the atmosphere: “It was literally phrased at DARPA that ‘some of these people were going to be taught a lesson [by] having their two-million-dollar-a-year contracts cut to almost nothing!’”

The first AI winter had begun. It would last until the early 1980s, when expert systems—a more modest, commercially-focused approach to artificial intelligence—temporarily revived interest before their own collapse triggered a second winter.

The frozen years: What happened from 1973-1980

The period from 1973 to 1980 wasn’t merely a slowdown—it was an existential crisis for the field. University AI labs that had thrived on government contracts suddenly found themselves begging for scraps. The University of Edinburgh’s Machine Intelligence Unit, which had been one of Europe’s premier AI centers, saw dramatic cuts. Stanford’s AI laboratory survived but shifted focus toward more immediately practical work.

Graduate students faced a grim choice: abandon years of research and retrain in more fundable areas like databases or operating systems, or persist in a field that offered few job prospects. Many of the brightest minds scattered to industry positions that had nothing to do with AI. The brain drain was substantial—researchers who might have made crucial breakthroughs in the 1980s instead spent those years building conventional software systems.

The academic community grew hostile. “Artificial intelligence” became a toxic phrase. Researchers learned to rebrand their work as “expert systems,” “knowledge engineering,” or “heuristic programming” to avoid the stigma. Conference attendance plummeted. The flagship journal Artificial Intelligence, launched in 1970, struggled to fill its pages with quality submissions.

Yet beneath the frozen surface, important work continued. A few stubborn researchers kept pushing forward on neural networks despite Minsky and Papert’s devastating 1969 critique in Perceptrons. Others developed the theoretical foundations for what would later become expert systems. The winter, paradoxically, forced a maturation—survivors learned to make modest, verifiable claims rather than revolutionary promises.

The ELIZA effect and the illusion of understanding

To understand why Lighthill’s criticisms cut so deep, we need to examine the systems that defined early AI—and their profound limitations.

ELIZA, created by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT between 1964 and 1967, was the world’s first chatbot. Its most famous script, DOCTOR, simulated a Rogerian psychotherapist by using pattern matching and substitution rules to transform user statements into questions. Tell ELIZA “I am sad,” and it might respond “Why are you sad?” or “Does being sad bother you?”

The system was almost comically simple—just 200 lines of code implementing clever pattern matching. But something disturbing happened. Users began treating ELIZA as if it understood them. Weizenbaum’s own secretary asked him to leave so she could talk privately with the program. Patients in trials grew emotionally attached. People attributed insight, empathy, and wisdom to a system that was merely rearranging their own words.

Weizenbaum called this the “ELIZA effect”—humans’ tendency to project understanding onto systems that merely mimic its appearance. He became so troubled by the phenomenon that he spent the rest of his career warning about the dangers of artificial intelligence, writing the influential 1976 book Computer Power and Human Reason. “The computer programmer is a creator of universes for which he alone is responsible,” Weizenbaum wrote. “Universes of virtually unlimited complexity can be created in the form of computer programs.”

SHRDLU, Terry Winograd’s 1968-1970 MIT project, demonstrated more sophisticated language understanding—but only within a virtual “blocks world” of colored blocks, pyramids, and boxes. Users could issue commands like “Find a block which is taller than the one you are holding and put it into the box,” and SHRDLU would execute them, answer questions about its actions, and even handle some pronoun disambiguation.

Winograd later acknowledged the system was a “Potemkin village”—impressive for demonstrations but fundamentally limited. It handled perhaps 50 words. It couldn’t manage ambiguity, metaphor, or anything outside its tiny domain. Extending it to real-world language proved impossible because of—yes—combinatorial explosion.

These systems revealed a crucial limitation: simulation is not duplication. A system could produce behaviors that looked intelligent without possessing anything resembling genuine understanding. This insight would haunt AI for decades.

The frame problem nobody solved

Beyond combinatorial explosion, Lighthill’s era grappled with what philosophers call the frame problem—a puzzle that still haunts artificial intelligence today.

Identified by John McCarthy and Patrick Hayes in their 1969 paper “Some Philosophical Problems from the Standpoint of Artificial Intelligence,” the frame problem asks: how do you represent what doesn’t change when something happens?

If a robot moves a cup from a table to a counter, the cup’s location changes. But its color doesn’t change. Its weight doesn’t change. The table’s color doesn’t change. The laws of physics don’t change. In formal logical systems, each of these non-changes needs explicit representation—requiring exponentially more “frame axioms” as systems grow more complex.

The narrow technical version of this problem has been partially solved through approaches like circumscription and non-monotonic logic. But the broader philosophical question—how cognitive systems determine what’s relevant in open-ended, dynamic environments—remains deeply challenging. How does a mind (or a machine) know what to pay attention to? How does it update beliefs efficiently without reconsidering everything? These questions animated the Lighthill debate and persist in contemporary AI.

The second winter: When expert systems promised too much

If the first AI winter resulted from academic overreach, the second came from commercial hubris. The 1980s saw an expert systems boom that made the 1970s hype look modest by comparison.

Expert systems were AI’s pragmatic pivot—highly specialized programs that captured human expertise in narrow domains through “if-then” rules. MYCIN, developed at Stanford between 1972 and 1976, diagnosed bacterial infections using about 600 production rules and achieved diagnostic accuracy comparable to human specialists (65% versus 42.5%-62.5% for physicians).

The commercial promise seemed limitless. By the mid-1980s, two-thirds of Fortune 500 companies had adopted expert systems. Software companies like Teknowledge and Intellicorp sold development tools. Universities offered courses. The market for specialized LISP machines—custom hardware optimized for running AI programs—grew to a half-billion dollar industry.

Then came 1987.

The collapse was swift and brutal. Desktop computers from Apple and IBM, which had been steadily improving, suddenly became powerful enough to run AI applications. A Sun workstation costing $10,000 could match the performance of a Symbolics LISP machine priced at $70,000 or more. The economic case for specialized hardware evaporated overnight.

Symbolics, the flagship LISP machine company, filed for bankruptcy by 1991. The entire specialized AI hardware market—worth hundreds of millions annually—was “demolished overnight,” as one historian put it. Over 300 AI companies shut down, went bankrupt, or were acquired by the end of 1993.

But the hardware collapse was merely a symptom. Expert systems themselves revealed fundamental flaws:

The Brittleness Problem: Expert systems worked perfectly within narrow domains but made catastrophic errors when faced with unexpected situations. A medical diagnosis system trained on bacterial infections might confidently (and disastrously) diagnose a viral condition.

The Knowledge Acquisition Bottleneck: Extracting expert knowledge into explicit rules was excruciatingly difficult and expensive. Experts often couldn’t articulate their tacit knowledge. “Knowledge engineers” spent months interviewing specialists, producing systems that required constant maintenance as the domain evolved.

The Maintenance Nightmare: Every exception needed a new rule. Systems grew to thousands of rules that interacted in unpredictable ways. Debugging became impossible. Companies discovered ongoing costs exceeded the value delivered.

The Scalability Wall: More rules didn’t produce better systems—they produced fragile, unmaintainable tangles. The dream of systems that could learn and adapt remained elusive.

By 1988, Jack Schwarz, who led DARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office, dismissed expert systems as “clever programming” and cut funding “deeply and brutally.” The Strategic Computing Initiative, America’s $1 billion answer to Japan’s Fifth Generation project, was “eviscerated.”

The second AI winter had arrived. It would last until the late 1990s, when neural networks and statistical machine learning finally offered an alternative paradigm.

The philosophical questions that refuse to die

The Lighthill debate wasn’t just about funding or technology—it engaged fundamental questions about the nature of mind that philosophers still wrestle with today.

Hubert Dreyfus, the Berkeley philosopher who spent decades criticizing AI, argued that intelligence is fundamentally embodied. Drawing on Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, Dreyfus claimed that human cognition emerges from “being-in-the-world”—from having a body that moves through space, feels temperature, experiences hunger and fatigue. Knowledge, he argued, is largely tacit—we know how to ride a bicycle without being able to articulate the rules—and cannot be captured in formal symbol systems.

John Searle’s Chinese Room argument (1980) attacked the idea that computation alone could produce understanding. Imagine a person in a room who follows English instructions to manipulate Chinese symbols, producing outputs indistinguishable from a native speaker. The person still doesn’t understand Chinese—they’re just following syntactic rules. “Syntax is not sufficient for semantics,” Searle concluded. Running a program cannot create genuine comprehension.

The symbol grounding problem, identified by Stevan Harnad in 1990, asks how formal symbols connect to what they represent. If an AI’s concept of “apple” consists only of relationships to other symbols (red, fruit, edible), how does it connect to actual apples in the world? Without grounding, critics argue, AI remains what Harnad called “uninterpreted squiggles.”

These philosophical challenges informed Lighthill’s skepticism. If intelligence requires embodiment, grounding, or something beyond formal symbol manipulation, then scaling up symbolic systems—no matter how sophisticated—would never achieve true artificial intelligence.

The debate echoes in contemporary discussions of large language models. When ChatGPT produces coherent essays, is it understanding language or merely manipulating statistical patterns? The philosophical questions Lighthill’s generation grappled with haven’t been answered—they’ve merely been deferred.

Today’s AI boom: A study in déjà vu

Fifty years after Lighthill’s report, we’re experiencing an AI boom that dwarfs anything the 1970s researchers could have imagined. The numbers are staggering:

- $202.3 billion invested in AI in 2025 (through Q3), up 75% from 2024

- AI companies represent 53% of global VC deal value despite being only 32% of funded companies

- Foundation model companies (OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI) alone captured 40% of global AI funding in 2025

- The United States commands 79% of AI funding globally, with the San Francisco Bay Area accounting for $122 billion

- Late-stage AI companies command a 100% valuation premium over non-AI peers at Series C

- Average AI startup valuations are 3.2x higher than traditional tech companies

OpenAI raised $40 billion from SoftBank in March 2025—the largest venture round in history. Anthropic secured $13 billion in Q3 2025. xAI raised $10 billion. The concentration of capital in foundation model companies is unprecedented.

Yet beneath the euphoria, cracks are forming.

The failures mounting in real time

The technology has advanced spectacularly, but high-profile failures have accumulated with alarming frequency:

McDonald’s AI Drive-Thru Disaster (June 2024): After piloting IBM’s AI ordering system in over 100 locations, McDonald’s abruptly terminated the partnership. Viral TikTok videos showed the system unable to stop adding items—one order reached 260 McNuggets as customers pleaded with the AI to stop. The company still believes in voice ordering’s potential but acknowledged the technology wasn’t ready.

Air Canada Chatbot Liability (February 2024): Jake Moffatt consulted Air Canada’s chatbot about bereavement fares after his grandmother’s death. The chatbot incorrectly stated he could purchase a ticket and apply for a discount within 90 days. When the airline denied his refund, Moffatt took them to tribunal—and won. The tribunal rejected Air Canada’s astonishing argument that “the chatbot is a separate legal entity responsible for its own actions.” The ruling established that companies remain liable for their AI systems’ outputs. Air Canada paid over CAD$1,000 in damages and faced global embarrassment.

NYC MyCity Chatbot Misinformation (March 2024): Microsoft’s MyCity chatbot, launched to help New York entrepreneurs, provided spectacularly wrong legal advice. It incorrectly suggested business owners could take cuts of workers’ tips, fire employees who complained of sexual harassment, and serve food with rodent parts if customers weren’t informed. The chatbot—meant to empower small businesses—encouraged them to break multiple labor and health laws.

Grok’s False Accusation (April 2024): Elon Musk’s Grok chatbot falsely accused NBA star Klay Thompson of vandalism, apparently misinterpreting basketball slang about “throwing bricks” (missing shots). The incident highlighted how statistical language models can generate plausible-sounding but entirely fabricated claims.

According to Stanford’s AI Index Report 2025, documented AI safety incidents surged 56.4% from 2023 to 2024—from 149 incidents to 233. These aren’t edge cases; they span finance, healthcare, transportation, retail, and government services.

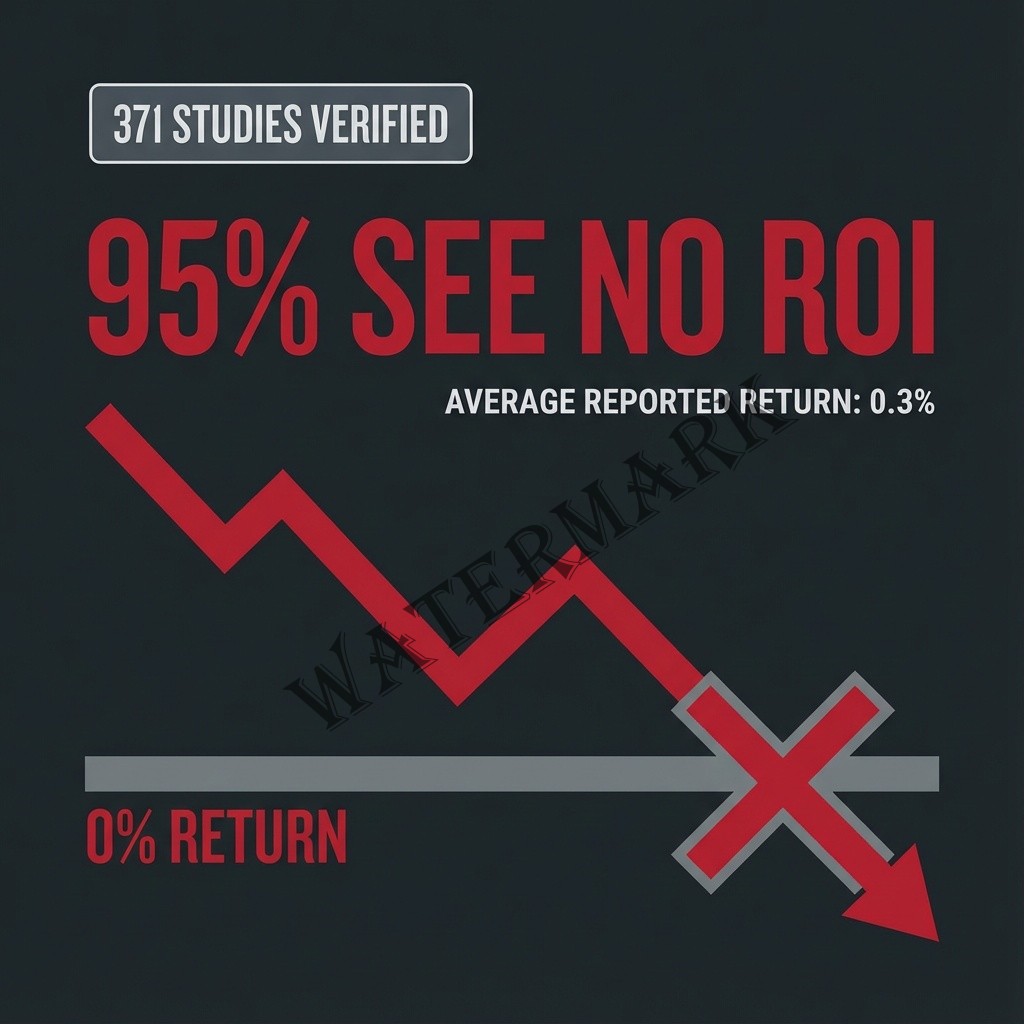

Perhaps most damning: a 2025 MIT study found that 95% of organizations that invested in generative AI were getting “zero return“—approximately $30 billion in destroyed shareholder value in 2024 alone. An S&P Global survey found 42% of companies had abandoned most AI initiatives, up from 17% the previous year.

The echoes of Lighthill’s critique

Yann LeCun, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist and Turing Award winner, has become a prominent skeptic of current approaches. “LLMs don’t have any underlying model of the world,” he explained at the New York Academy of Sciences in March 2024. “They can’t really reason. They can’t really plan. They basically just produce one word after the other, without really thinking in advance about what they’re going to say.” In June 2024, he advised PhD students: “Don’t work on LLMs. Try to discover methods that would lift the limitations of LLMs.”

Rodney Brooks, former director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, issued an even starker warning in his January 2024 predictions scorecard: “Get your thick coats now. There may be yet another AI winter, and perhaps even a full-scale tech winter, just around the corner. And it is going to be cold.”

Gary Marcus, NYU Professor Emeritus and longtime AI researcher, told IEEE Spectrum in September 2024: “There’s a financial bubble because people are valuing AI companies as if they’re going to solve artificial general intelligence. In my view, it’s not realistic. I don’t think we’re anywhere near AGI.”

The concerns aren’t merely theoretical or pessimistic. Even optimists acknowledge challenges:

Jeff Bezos, speaking at Italian Tech Week in October 2025, offered measured perspective: “This is a kind of industrial bubble… Investors have a hard time in the middle of this excitement distinguishing between the good ideas and the bad ideas. And that’s also probably happening today.” But he added: “The [bubbles] that are industrial are not nearly as bad, it can even be good, because when the dust settles and you see who are the winners, societies benefit from those inventions.”

Hallucinations and the ghost of combinatorial explosion

Modern AI’s most visible limitation—hallucination—recalls Lighthill’s fundamental critique. Large language models confidently generate plausible but false information: fabricated legal citations (as in the infamous Mata v. Avianca case where a lawyer was sanctioned for submitting ChatGPT-invented case law), incorrect medical information, nonexistent sources, and false historical claims.

A January 2024 academic paper titled “Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models” argues this isn’t a bug to be fixed but a fundamental feature of the architecture. The paper demonstrates that for certain types of queries, no amount of training or parameter tuning can eliminate hallucinations—they’re mathematically inevitable given how these systems work.

OpenAI’s own 2025 research acknowledges that “accuracy will never reach 100%.” Retrieval-augmented generation can reduce hallucinations by 60-80%, but cannot eliminate them. The statistical nature of language models means they will always sometimes be confidently wrong.

This echoes the combinatorial explosion that doomed 1970s AI. Then, systems couldn’t scale from toy problems to reality because the solution space grew exponentially. Now, systems can generate impressive outputs but can’t reliably distinguish truth from plausible-sounding fiction. The limitation is different but equally fundamental.

The scaling debate—whether throwing more compute and data at large language models will eventually produce human-level intelligence—echoes the debates of 1973. Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI co-founder, told NeurIPS 2024 that “pretraining as we know it will end” and that “the 2010s were the age of scaling, now we’re back in the age of wonder and discovery.”

Reports from Bloomberg and The Information suggest OpenAI’s Orion model underperformed expectations; Google’s Gemini iterations reportedly aren’t meeting internal targets. The era of predictable performance gains from simply adding parameters may be ending—precisely the kind of wall Lighthill identified in 1973.

The stochastic parrot critique

The “stochastic parrot” critique, articulated by Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, and colleagues in their influential 2021 paper “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?”, argues that LLMs are “haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms… according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning.”

The phrase—named 2023 AI Word of the Year by the American Dialect Society—captures a crucial insight: these systems manipulate symbols with stunning sophistication but lack genuine understanding of what the symbols represent. They’re parrots because they reproduce linguistic patterns; they’re stochastic because their outputs are probabilistic rather than grounded in comprehension.

This distinction matters profoundly. A system that truly understands language would recognize when it’s about to make a false claim. A statistical pattern matcher cannot—it can only generate the most probable continuation based on training data, regardless of truth value.

Lighthill would recognize this limitation instantly. It’s the same problem he identified with early AI: systems that simulate intelligence without possessing it, that work spectacularly in constrained domains but fail unpredictably when the context shifts.

What Lighthill teaches us about hype and humility

The 1973 report wasn’t a rejection of artificial intelligence research—it was a demand for honesty about limitations. Lighthill supported practical applications and scientific research into cognition. What he rejected was the uncritical conflation of narrow achievements with progress toward general intelligence.

That distinction remains vital. Current AI systems excel at specific tasks: pattern recognition, language generation, data analysis, code completion. They struggle with genuine reasoning, planning beyond trained scenarios, common-sense understanding, and reliable factual accuracy.

The Winograd Schema Challenge—tests requiring commonsense pronoun disambiguation—shows LLMs passing standard versions but failing on novel formulations, suggesting pattern matching rather than genuine understanding. When asked “The trophy doesn’t fit in the brown suitcase because it’s too large. What is too large?” humans immediately know “it” refers to the trophy. GPT-4 gets this right. But change the scenario slightly or use unfamiliar objects, and performance degrades sharply.

This brittleness—spectacular performance on training distribution, unpredictable failure on novel inputs—is precisely what Lighthill criticized in 1973. The technology has advanced enormously, but the fundamental challenge persists: narrow competence doesn’t generalize to genuine intelligence.

The path forward requires the past

James Lighthill died in 1998 while swimming around the island of Sark in the Channel Islands—an appropriately adventurous end for a man who spent his life navigating complex systems. He never lived to see deep learning’s triumphs or GPT-4’s bar exam scores.

But his fundamental insight remains prescient: progress on constrained problems doesn’t automatically translate to progress on general intelligence. The combinatorial explosion hasn’t been defeated—it’s been partially circumvented through massive computation and clever approximation. The frame problem hasn’t been solved—it’s been sidestepped through statistical approaches that don’t require explicit logical representation. The symbol grounding question hasn’t been answered—it’s been deferred through systems that operate entirely in linguistic space.

Whether current approaches can eventually achieve human-level intelligence remains genuinely uncertain. Sam Altman claims “we know how to build AGI.” Yann LeCun says machines achieving human-level intelligence will take “several more decades.” The gulf between these predictions—both from people with deep technical knowledge—should give us pause.

What the Lighthill Report teaches is the value of epistemic humility. The 1970s AI researchers weren’t frauds—they were genuine scientists who made real discoveries. But they allowed enthusiasm to outrun evidence, and the field paid a devastating price. The 1980s expert systems builders weren’t scammers—they delivered real value in narrow domains. But they oversold scalability, and another winter followed.

Today’s AI leaders would do well to remember that history. The technology is remarkable. The achievements are genuine. Large language models can pass bar exams, write functional code, and generate photorealistic images. These capabilities would have seemed impossible to Lighthill’s generation.

But conflating impressive language generation with understanding, or pattern matching with reasoning, or scaling curves with guaranteed progress toward general intelligence—these errors echo across fifty years. The winter of 1973-1980 wasn’t inevitable. It resulted from overpromising, underfunding verification research, and dismissing critics as Luddites.

If today’s AI community can maintain honesty about limitations while pursuing genuine advances, it may avoid repeating that painful history. The technology has enormous potential to improve human welfare—if deployed with appropriate skepticism about its capabilities and appropriate safeguards against its limitations.

And if it cannot? Well, as Rodney Brooks advises: get your thick coats now.

References

- Agar, J. (2020). What is science for? The Lighthill report on artificial intelligence reinterpreted. The British Journal for the History of Science, 53(3), 289-310. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087420000230

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610-623.

- Crunchbase. (2025). AI funding trends 2025. Retrieved from https://news.crunchbase.com/ai/big-funding-trends-charts-eoy-2025/

- Dreyfus, H. L. (1992). What computers still can’t do: A critique of artificial reason. MIT Press.

- KPMG Private Enterprise. (2025). Venture Pulse Q3 2025. Retrieved from https://kpmg.com/xx/en/media/press-releases/2025/10/global-vc-investment-rises-in-q3-25.html

- Lighthill, J. (1973). Artificial intelligence: A general survey. In Artificial Intelligence: A Paper Symposium. Science Research Council.

- McCarthy, J., & Hayes, P. J. (1969). Some philosophical problems from the standpoint of artificial intelligence. Machine Intelligence, 4, 463-502.

- Mintz. (2025). The state of the funding market for AI companies: A 2024-2025 outlook. Retrieved from https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2166/2025-03-10-state-funding-market-ai-companies-2024-2025-outlook

- Moffatt v. Air Canada. (2024). 2024 BCCRT 149. British Columbia Civil Resolution Tribunal.

- Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(3), 417-424.

- Stanford University. (2025). AI Index Report 2025. Stanford Human-Centered AI Institute.

- Weizenbaum, J. (1966). ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, 9(1), 36-45.

- WIPO Global Innovation Index. (2025). Artificial intelligence megadeals fuel venture capital rebound. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/en/web/global-innovation-index/w/blogs/2025/ai-venture-capital

Additional Reading

- Crevier, D. (1993). AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence. Basic Books. [Comprehensive historical overview including detailed analysis of both AI winters]

- McCorduck, P. (2004). Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence (2nd ed.). A.K. Peters. [First-hand accounts from AI pioneers]

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (4th ed.). Pearson. [Chapter 1 provides historical context; Chapter 27 discusses philosophical foundations]

- Wooldridge, M. (2020). The Road to Conscious Machines: The Story of AI. Pelican Books. [Accessible history connecting past challenges to current developments]

- Mitchell, M. (2019). Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Contemporary perspective on AI limitations and capabilities]

Additional Resources

- Original Lighthill Report PDF – Chilton Computing Archive: http://www.chilton-computing.org.uk/inf/literature/reports/lighthill_report/ [Complete text of the 1973 report with original formatting]

- 1973 BBC Debate Video/Transcript – University of Edinburgh AIAI Archive: https://www.aiai.ed.ac.uk/events/lighthill1973/ [Historical footage and transcript of the Lighthill-McCarthy-Michie debate]

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: The Frame Problem: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/frame-problem/ [Comprehensive philosophical analysis of a core challenge Lighthill identified]

- Rodney Brooks’ Annual Predictions Scorecard: https://rodneybrooks.com/predictions-scorecard-2024-january-01/ [Track record of AI predictions with accountability—includes AI winter warnings]

- AI Incident Database: https://incidentdatabase.ai/ [Comprehensive database of documented AI failures and safety incidents]

Leave a Reply