Or: How Margot Vance Learned That Being Really Good at One Thing Beats Being Okay at Everything

Margot discovers that AI specialization beats generalization.

See why 70% of AI value comes from vertical, domain-specific solutions—not Swiss Army knives.

Margot Vance was having the kind of nightmare that only happens when you’re both awake and completely sober.

It was 11:47 PM on a Tuesday, and she was staring at a laptop screen in her kitchen, illuminated only by the glow of her “AeroStream Innovation Dashboard” and the accusatory blinking of her coffee maker’s clock. The dashboard, which she’d spent six months building, looked like a cardiovascular patient’s EKG mid-heart attack—all sharp drops and panicked spikes.

The problem? A company Margot had never heard of was systematically dismantling AeroStream’s market share in the Northeast corridor like a particularly efficient termite colony.

Their name was OrganicRoute. They’d launched eight months ago. They had 47 employees. And according to the analytics Margot had been obsessively refreshing since dinner, they’d just poached three of AeroStream’s most lucrative accounts in the specialty food distribution sector.

“How is this possible?” Margot muttered to her laptop, as if it might apologize and offer to fix things. The laptop, predictably, said nothing. But the numbers on the screen told a story Margot didn’t want to hear: OrganicRoute wasn’t just competing with AeroStream. They were annihilating them—but only in one very specific lane.

The email from the CFO, received at 9:14 PM, had been characteristically blunt: “Margot, we need to talk about OrganicRoute. They’re eating our lunch in perishable artisan goods. What’s our AI doing about this? Weren’t we supposed to be ‘leveraging machine learning for competitive advantage’? Schedule a call tomorrow. Early.”

Margot had Googled OrganicRoute immediately. Their website was annoyingly elegant, full of smiling farmers holding heirloom tomatoes and confident declarations about “AI-powered cold chain optimization for organic produce.” They had case studies. They had testimonials from boutique grocery chains raving about “99.7% on-time delivery rates for temperature-sensitive items.”

And here was the truly infuriating part: they were using AI. But not the kind of general-purpose, Swiss Army knife, “we can do everything for everyone” AI that AeroStream had invested millions into developing.

OrganicRoute’s AI did exactly one thing: move organic, temperature-sensitive food from farms to tables without letting anything rot, wilt, or arrive looking like it had survived a demolition derby.

That was it. That was the whole business model.

And it was working. Spectacularly.

[IMAGE PLACEMENT 1: Margot’s Midnight Crisis]

Visual: Stressed professional woman at kitchen table late at night, illuminated only by laptop screen showing declining analytics graphs. Coffee mug nearby. Dark, moody lighting captures the isolation and intensity of the moment. This image sets the scene for Margot’s crisis and draws readers into her late-night discovery.

Chapter One: The 2 AM Revelation (Or: When Google Search Becomes Your Therapist)

Margot made fresh coffee—the good stuff, not the sludge that lived in the office break room—and settled into what she was already thinking of as “research mode.” This was the phase of problem-solving where panic transforms into hyperfocus, usually somewhere between midnight and dawn.

She started with the basics: What were OrganicRoute’s competitors saying about them? What made their AI different? And most critically, why hadn’t AeroStream’s supposedly sophisticated AI platform seen them coming?

The answer, as it turned out, was hiding in plain sight.

OrganicRoute didn’t use a large language model trained on the entire internet. They didn’t have a chatbot that could write poetry or explain quantum mechanics. Their AI couldn’t generate marketing copy or analyze sentiment in customer reviews.

What their AI could do was predict, with unsettling accuracy, exactly when an organic strawberry would transition from “Instagram-worthy” to “composting candidate” based on harvest date, transportation conditions, ambient temperature, humidity levels, and seventeen other variables that Margot’s general-purpose system treated as background noise.

According to an interview Margot found at 1:23 AM, OrganicRoute’s CEO had said something that made her stomach drop: “We’re not trying to be the smartest AI in the room. We’re trying to be the only AI that actually understands strawberries.”

Margot stared at that quote for a full minute.

Then she opened a new browser tab and typed: “vertical AI vs horizontal AI.”

What unfolded over the next hour was something between an education and an existential crisis. Article after article, report after report, all telling the same story: the era of general-purpose AI dominance was ending. The future belonged to the specialists.

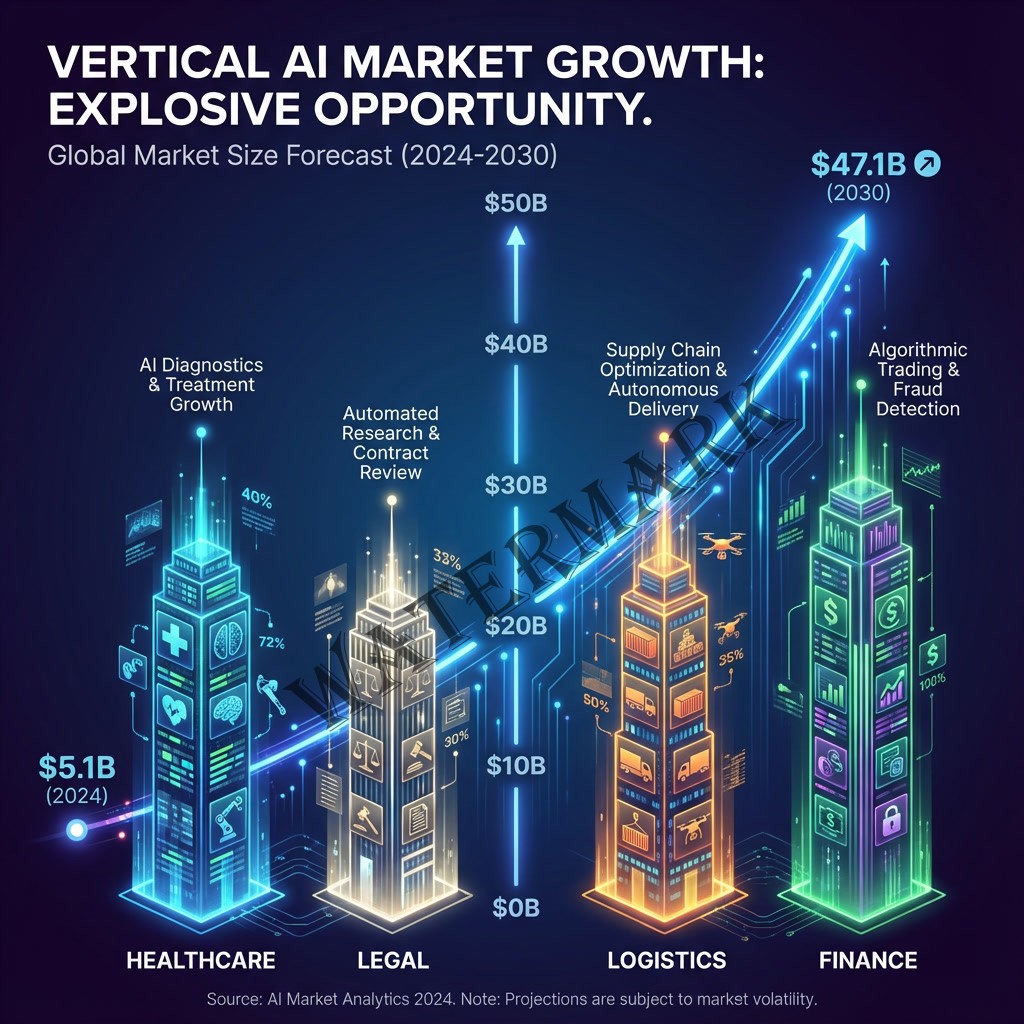

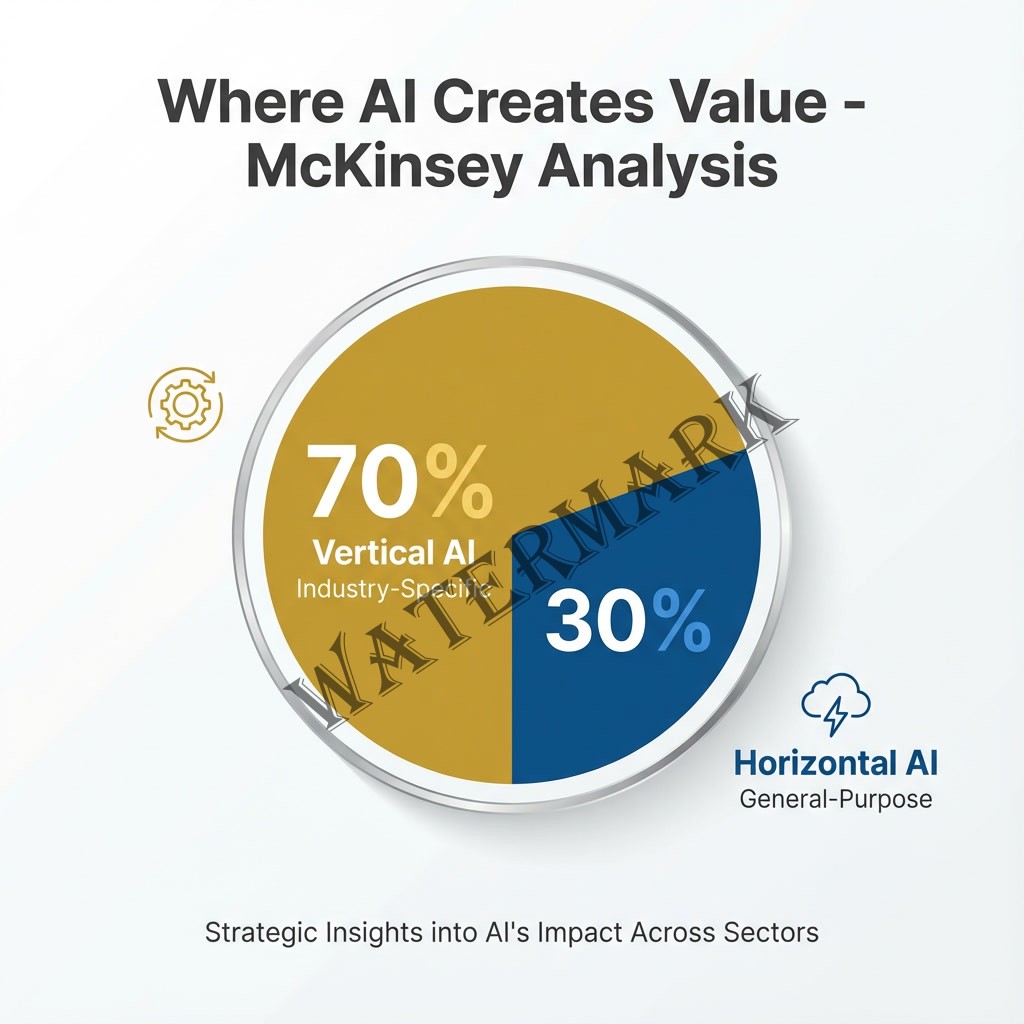

McKinsey estimated that over 70% of AI’s total value potential would come from vertical—industry-specific—AI applications (Unite.AI, 2025). Gartner predicted that more than 80% of enterprises would use vertical AI by 2026 (Turing, 2025). The vertical AI market, currently valued at $5.1 billion, was projected to balloon to $47.1 billion by 2030 and potentially exceed $100 billion by 2032 (Unite.AI, 2025).

The numbers told a stark truth: specialized AI wasn’t just competitive with general-purpose systems. It was crushing them.

And here was AeroStream, with its beautiful, versatile, magnificently general AI platform that could theoretically handle anything from automotive parts to zoo animals, being outmaneuvered by an AI that cared only about keeping lettuce crispy.

Margot closed her laptop at 2:47 AM. She didn’t go to bed. Instead, she sat in her dark kitchen and thought about strawberries.

Chapter Two: The Boardroom Reckoning (Or: How to Explain You’ve Been Building the Wrong Thing for Two Years)

The 8:00 AM call with the CFO did not go well.

“Let me make sure I understand,” Marcus said, his voice carrying that particular timbre that meant someone was about to get promoted or fired and he hadn’t decided which yet. “You’re telling me that a startup with a staff smaller than our marketing department is dominating us in perishable goods because their AI is… narrower than ours?”

“Not narrower,” Margot said, choosing her words with surgical precision. “More focused. Domain-specific. They’re using vertical AI.”

Marcus made the kind of sound usually reserved for discovering someone has been storing fish in the communal office fridge. “Margot. We spent four million dollars building an AI that can handle any logistics scenario. Multi-modal transportation. International customs. Hazmat regulations. Real-time rerouting. Machine learning that adapts to—”

“To everything,” Margot interrupted. “Which means it’s optimized for nothing.”

The silence on the other end of the call was deafening.

“Explain,” Marcus said finally.

Margot pulled up the presentation she’d built between 3:00 AM and 7:45 AM, running on caffeine and the peculiar clarity that comes from realizing you’ve been fundamentally wrong about something important.

“OrganicRoute’s AI doesn’t care about automotive parts,” she began. “It doesn’t need to understand customs regulations for electronics. It doesn’t waste computational resources learning about shipping containers. It knows one thing: how to move temperature-sensitive organic produce from Point A to Point B without degradation. That’s the entire model.”

She pulled up a slide showing the comparative accuracy rates. OrganicRoute’s system predicted spoilage with 97.3% accuracy. AeroStream’s general system, when applied to the same problem, hit 73.8%.

“That twenty-four-point gap,” Margot said quietly, “is worth millions in reduced waste and higher customer satisfaction. That’s why we’re losing accounts.”

Marcus was silent for a long moment. Then: “So what you’re telling me is that we built a Swiss Army knife when our customers needed a scalpel.”

“That’s… actually a perfect metaphor,” Margot admitted.

“How do we fix it?”

Chapter Three: The Pivot (Or: Learning to Love Your Limitations)

Jake Heller, the CEO of Casetext—a legal AI company acquired by Thomson Reuters for $650 million—had said something that Margot taped to her computer monitor: “To automate mission-critical tasks, general-purpose AI isn’t enough—you need domain-specific integration, precision, and accuracy at nearly 100%” (Turing, 2025).

Ninety-nine percent. Not eighty. Not even ninety-five.

Mission-critical domains didn’t tolerate margin for error. A lawyer couldn’t present a brief that was “mostly accurate.” A radiologist couldn’t diagnose cancer with “pretty good confidence.” A specialty food distributor couldn’t deliver organic produce that was “somewhat fresh.”

General-purpose AI was built for “good enough.” Vertical AI was built for “absolutely certain.”

And AeroStream, Margot realized with a mixture of dread and excitement, needed to pick a lane.

The next three weeks were a masterclass in strategic retrenchment. Margot and her team analyzed AeroStream’s customer base, revenue streams, and operational capabilities with the kind of ruthless focus usually reserved for triage surgeons. They weren’t looking for what they could do. They were looking for what they could do better than anyone else.

The answer, when it emerged, was both obvious and terrifying: perishable artisan goods.

AeroStream already had the relationships. They had distribution centers in key locations. They had drivers who understood the difference between regular refrigeration and climate-controlled transport. What they didn’t have was an AI that cared.

“Here’s what we’re proposing,” Margot told the executive team in a presentation that would either save her career or end it. “We stop trying to be a general logistics AI company. We become the logistics AI company for high-end perishable goods. Artisan cheeses. Small-batch wines. Organic produce. Craft chocolates. Products where timing and temperature control mean the difference between premium pricing and total loss.”

She pulled up market analysis data. The high-end perishable market was valued at $47 billion in the U.S. alone, growing at 8.3% annually. These weren’t commodity products. These were items where customers would pay a premium—a significant premium—for guaranteed freshness and proper handling.

“Vertical AI solutions capture 25 to 50 percent of an employee’s economic value by automating entire workflows,” Margot continued, citing research she’d absorbed during her late-night crash course, “compared to horizontal AI’s 1 to 5 percent efficiency gains” (AI News International, 2025). “This isn’t about building a better general tool. It’s about building a tool so specialized that it becomes indispensable.”

The CFO leaned back in his chair. “So instead of competing with everyone, everywhere, we compete with almost no one in one very specific place.”

“Exactly,” Margot said. “It’s called building a moat. The deeper and more specialized our expertise becomes, the harder we are to displace.”

Chapter Four: The Rebuild (Or: Teaching Your AI to Care About Cheese)

What followed was the kind of project that makes you question your career choices on an hourly basis.

Building a vertical AI wasn’t just about narrowing focus. It required fundamentally rethinking their data, their models, and their entire approach to machine learning. General-purpose AI models were trained on diverse data from across the internet. Vertical AI models needed to be trained on highly specialized, domain-specific data.

Margot’s team spent weeks collecting data they’d previously considered peripheral: ripening curves for different cheese varieties, temperature sensitivity thresholds for heirloom tomatoes, optimal humidity ranges for artisan bread, vibration tolerance for wine bottles. They interviewed farmers, artisan producers, specialty retailers, and even food scientists.

This was the kind of knowledge that didn’t exist in generic datasets. It lived in the heads of people who’d spent decades in the industry. And capturing it, codifying it, and training an AI to understand it was painstaking work.

PathAI, a company specializing in AI-powered digital pathology, had demonstrated this principle in the medical field. Their AI models were trained on large-scale, expertly annotated medical datasets to support the analysis of tissue samples, enabling pathologists to detect disease markers with precision that general-purpose computer vision systems couldn’t match (The Healthcare Technology Report, 2025). The company had raised $355.2 million in funding and partnered with major pharmaceutical companies not because their AI was broadly applicable, but because it was narrowly excellent (AI-Startups, 2025).

That was the bar. Narrow excellence.

Margot’s technical lead, Sarah—the same analyst who’d been terrified of AI replacing her job six months ago—had become the project’s unlikely champion. “You know what’s interesting?” Sarah said during one of their late-night coding sessions. “The AI doesn’t need to understand logistics in general anymore. It just needs to understand our logistics. That makes the problem smaller and the solution better.”

It was a profound observation. By limiting scope, they’d actually reduced complexity. And by reducing complexity, they’d increased accuracy.

Three months into the rebuild, they ran their first production test: a shipment of farmstead cheeses from Vermont to high-end retailers in Manhattan. The order included seven varieties, each with different aging profiles and temperature sensitivities.

AeroStream’s new vertical AI—they’d named it “ArtisanRoute” in a nod to their competition—predicted optimal routing, recommended climate controls for each vehicle segment, and flagged a potential humidity issue at one distribution center thirty-six hours before the shipment was scheduled to arrive.

The cheese arrived in perfect condition. The customer, a boutique cheese shop in SoHo, sent a thank-you note that Margot framed.

Chapter Five: The Economics of Specialization (Or: Why Narrow Beats Broad)

Six months after the pivot, AeroStream’s financials told a story that would have seemed impossible a year earlier.

Revenue from their perishable artisan goods division had grown 127%. Customer retention in that sector hit 94%—an unheard-of number in logistics. And profit margins, freed from the burden of trying to serve every possible customer with increasingly complex general tools, had actually increased.

Tom Biegala, co-founder of Bison Ventures, had predicted this shift: “In 2025, the AI hype cycle will give way to the rise of domain-specific, specialized AI and robotics. Products will be faster and more efficient while delivering immediate, tangible value compared to general-purpose solutions” (AIM Media House, 2025).

The data backed up the prediction. Organizations using vertical AI saw a 25% higher return on investment compared to those relying on general-purpose AI (Unite.AI, 2025). And companies using vertical AI agents were reporting growth rates of 400% year-over-year, reaching 80% of traditional SaaS contract values (Turing, 2025).

The economics were brutally simple: vertical AI captured more value because it solved complete problems rather than offering marginal improvements.

A lawyer using Harvey, an AI-powered legal assistant, didn’t just draft contracts faster—the system performed contract analysis, due diligence, and compliance checks that previously required human associates (AI News International, 2025). A healthcare provider using Abridge didn’t just record patient notes faster—the platform transcribed conversations, generated clinical summaries, and freed physicians to see more patients while maintaining higher job satisfaction.

When a software solution handled core work instead of just streamlining it, customers didn’t just tolerate higher prices—they demanded access because the ROI was undeniable.

AeroStream was experiencing this firsthand. Their new vertical AI didn’t just optimize routes (something their old general AI could do). It prevented spoilage, reduced waste, guaranteed freshness, protected brand reputation, and enabled their customers to command premium prices. The value proposition wasn’t “we’re 10% more efficient.” It was “we ensure your $40-per-pound cheese arrives in perfect condition.”

That was worth paying for.

Chapter Six: The Philosophical Question (Or: What We Lose When We Specialize)

But success brought its own existential questions.

One evening, Margot found herself in a surprisingly candid conversation with Marcus over coffee—real coffee, from a local roaster whose beans they now transported with ArtisanRoute.

“We’re really good at one thing now,” Marcus mused. “But we’re deliberately bad at everything else. Does that bother you?”

It was the kind of question Margot had been avoiding. AeroStream’s general AI platform had represented a particular vision of the future: intelligence that could adapt to anything, handle any challenge, solve any problem. Vertical AI represented something different: intelligence that knew its limits and stayed within them.

This tension sat at the heart of the vertical AI revolution. By choosing specialization, companies weren’t just changing their product strategy—they were making philosophical statements about the nature of intelligence itself.

General AI embodied the belief that intelligence, at its core, was about flexibility and adaptability. A truly intelligent system should be able to learn new domains, transfer knowledge across contexts, and handle novel situations with grace. This was the promise of artificial general intelligence—and it remained, as of 2026, largely aspirational.

Vertical AI embodied a different belief: that value came not from knowing everything, but from mastering something. That depth mattered more than breadth. That the path to exceptional performance wasn’t through generalization, but through specialization so complete that the system became irreplaceable within its domain.

This wasn’t just an AI question. It was a question humans had wrestled with forever. Was it better to be a Renaissance person, skilled at many things, or a master craftsperson, peerless at one? Was the future built by generalists who could connect disparate ideas, or specialists who could push boundaries in narrow fields?

The answer, Margot had come to believe, was probably “both.” But for AI in 2026, specialization was winning. Not because generalization was wrong, but because the technology wasn’t there yet to make general-purpose AI reliable enough for mission-critical applications.

“You know what doesn’t bother me?” Margot said to Marcus. “That we’re really, really good at helping a farmer get their organic strawberries to market before they go bad. That’s a real problem. We’re solving it better than anyone. And the farmer doesn’t need us to also book their flight to a trade show or translate the shipping manifest into Mandarin.”

Marcus considered this. “So we’re not building artificial general intelligence.”

“No,” Margot agreed. “We’re building artificial specific intelligence. And for now, at least, that’s enough.”

Chapter Seven: The Unexpected Upside (Or: What Sarah Discovered)

The irony of vertical AI was that narrowing focus had actually expanded possibilities.

Sarah discovered this three months into the ArtisanRoute rollout when a small cheese producer in Wisconsin called with an unusual request. They wanted to ship a limited-edition, cave-aged Gruyère to restaurants in San Francisco, but the cheese needed to be maintained at precisely 54 degrees Fahrenheit with 85% humidity—conditions that would require custom transport solutions.

With AeroStream’s old general AI, this would have been filed under “special handling” and routed to human managers who would figure out logistics manually. With ArtisanRoute’s vertical AI, the system not only understood the requirements—it suggested a routing solution that included a new refrigerated shipping partner they’d never worked with before, specifically because that partner specialized in high-humidity cheese transport.

The shipment was perfect. The restaurants were ecstatic. The cheese producer signed a contract for monthly shipments.

“The AI knew about specialized cheese transport carriers?” Margot asked Sarah in disbelief.

“That’s the thing,” Sarah explained. “Because ArtisanRoute only cares about perishable artisan goods, every partner in its database, every vehicle specification, every routing algorithm, every weather prediction model—all of it is filtered through that lens. It’s not trying to be smart about everything. It’s trying to be genius at cheese.”

This was the hidden advantage of vertical AI: by eliminating the noise of irrelevant information, specialized systems could actually go deeper in their domains than general systems could.

Tempus, a healthcare technology company focused on precision medicine, had demonstrated this principle at scale. Their AI processed clinical and molecular data across oncology, cardiology, and other specialties, building proprietary datasets that no general-purpose system could match (The Vertical AI Revolution, 2025). The company went public in June 2024 and had expanded its services to approximately 3,000 U.S. providers through partnerships with insurance networks (Techie Visions, 2025).

The depth of Tempus’s specialized knowledge created a competitive moat that was nearly impossible to cross. General AI companies couldn’t compete because they didn’t have the specialized data. And new entrants couldn’t compete because accumulating that data took years of focused effort in the specific domain.

AeroStream was building the same kind of moat, one specialty food shipment at a time.

Chapter Eight: The Quiet Victory (Or: How Margot Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Niche)

One year after Margot’s 2 AM discovery of OrganicRoute, AeroStream hosted its annual all-hands meeting. The mood was different than it had been in previous years. There was less talk about “transforming the industry” and “disrupting logistics” and more focus on quieter, more specific victories.

They’d successfully shipped 12,000 orders of temperature-sensitive artisan goods with a 99.1% on-time, undamaged delivery rate. They’d expanded their partner network to include 47 small-batch producers. Their NPS score in the perishable goods sector was 78—almost unheard of in logistics.

And OrganicRoute? They were still around, still successful. But they were no longer the existential threat they’d seemed a year ago. Because AeroStream had stopped trying to beat them at everything and started focusing on being unbeatable at something specific.

During the Q&A, a junior analyst asked Margot about future plans. “Do we expand into other verticals? Or do we stay focused on perishable artisan goods?”

It was the right question.

“Here’s what I’ve learned,” Margot said. “The temptation is always to broaden. To take what’s working in one domain and apply it everywhere. To go back to being general because general feels like more opportunity.”

She paused, thinking about strawberries. About cheese. About all the late nights trying to understand why one very specific AI could beat a very general one.

“But that’s the trap,” she continued. “The real opportunity is going deeper, not wider. Every time we solve a problem in artisan perishables, we learn something that makes us better at the next problem in artisan perishables. We’re not building general logistics expertise. We’re building unfathomable depth in one specific domain. And that depth is what makes us valuable.”

She pulled up a quote she’d saved from her research: “McKinsey estimates that over 70% of AI’s total value potential will come from vertical AI applications” (Unite.AI, 2025).

“Seventy percent,” Margot repeated. “Not from the systems that try to do everything. From the systems that do one thing so well that they become indispensable.”

The room was quiet. Then someone started clapping. And then someone else. And then the whole room.

Margot smiled. It wasn’t the kind of applause you got for announcing you were going to change the world. It was the kind you got for admitting you’d found your corner of it and decided that was enough.

Epilogue: The 2026 Reckoning

The great AI reckoning of 2026 wasn’t a single moment. It was a gradual realization spreading across industries: the future didn’t belong to AI systems that could do everything adequately. It belonged to AI systems that could do something specific extraordinarily well.

Healthcare saw the rise of vertical AI solutions like Abridge, which secured $757.5 million in funding to focus exclusively on medical conversation AI and clinical documentation (AI-Startups, 2025). Legal tech saw Harvey and CaseText (acquired for $650 million) dominate by specializing in legal workflows rather than trying to be general legal assistants (Turing, 2025).

The pattern was clear: 22% of healthcare organizations had implemented domain-specific AI tools by 2025—a 7x increase over 2024 (Menlo Ventures, 2025). Healthcare AI spending hit $1.4 billion, nearly tripling the previous year’s investment, surpassing entire vertical AI markets from law to design (Menlo Ventures, 2025).

These weren’t incremental improvements. They were step-function changes in capability, enabled by the decision to care deeply about one thing rather than superficially about everything.

Margot Vance kept the framed thank-you note from the cheese shop on her office wall. On particularly difficult days—and there were still plenty—she’d look at it and remember that sometimes the most radical thing you can do is narrow your focus until you become exceptional.

The future, it turned out, wasn’t about building AI that could pass the Turing Test across all domains. It was about building AI that could pass the practical test in specific domains. AI that a strawberry farmer would trust with their harvest. AI that a cheesemaker would trust with their cave-aged Gruyère. AI that solved real problems for real people so well that the technology became invisible and the results became essential.

That was vertical AI. That was the specialized moat.

And for Margot Vance, director of strategic transformation at a mid-sized logistics company that had learned to love its limitations, that was more than enough.

References

- AI News International. (2025). The AI business model showdown: Why vertical AI is eating horizontal platforms’ lunch. https://www.ainewsinternational.com/the-ai-business-model-showdown-why-vertical-ai-is-eating-horizontal-platforms-lunch/

- AIM Media House. (2025). Vertical AI agents will dominate 2025. https://aimmediahouse.com/ai-startups/vertical-ai-agents-will-dominate-2025

- AI-Startups. (2025). Top 188 startups developing AI for medicine and healthcare 2025. https://www.ai-startups.pro/top/medicine/

- Menlo Ventures. (2025). 2025: The state of AI in healthcare. https://menlovc.com/perspective/2025-the-state-of-ai-in-healthcare/

- NEA. (2025). Vertical AI explained: The next generation of tech titans. https://www.nea.com/blog/tomorrows-titans-vertical-ai

- Techie Visions. (2025). Must know top 10 AI healthcare startups ranking in 2025. https://techievisions.com/ai-healthcare-startups/

- The Healthcare Technology Report. (2025). The top 25 healthcare AI companies of 2025. https://thehealthcaretechnologyreport.com/the-top-25-healthcare-ai-companies-of-2025/

- The Vertical AI Revolution. (2025). Why SoundHound, BigBear, and Tempus AI are defining the market in late 2025. Financial Content. https://markets.financialcontent.com/wral/article/tokenring-2025-12-19-the-vertical-ai-revolution-why-soundhound-bigbear-and-tempus-ai-are-defining-the-market-in-late-2025

- Turing. (2025). How vertical AI agents are reshaping industries in 2025. https://www.turing.com/resources/vertical-ai-agents

- Unite.AI. (2025). How vertical AI agents are transforming industry intelligence in 2025. https://www.unite.ai/how-vertical-ai-agents-are-transforming-industry-intelligence-in-2025/

Additional Reading

- NEA. (2025). Vertical AI explained: The next generation of tech titans. https://www.nea.com/blog/tomorrows-titans-vertical-ai

A comprehensive framework for understanding vertical AI opportunities and the key considerations for creating category winners. - Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index 2025: State of AI in 10 charts. https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ai-index-2025-state-of-ai-in-10-charts

Data-driven insights into AI’s technical progress, economic influence, and societal impact across 2025. - Turing. (2025). How vertical AI agents are reshaping industries in 2025. https://www.turing.com/resources/vertical-ai-agents

Analysis of how vertical AI companies are achieving rapid growth while maintaining high contract values, including data from Bessemer Venture Partners research. - Appel, D. (2025). The vertical AI advantage: Why specialized systems of action will dominate 2026. Medium.

Deep dive into go-to-market efficiency and the economic advantages of specialized AI solutions, with analysis based on McKinsey research and the Benchmark.ai SaaS Finance Summit. - Digital Economy Compass. (2026). The rise of vertical AI. Digital Economy Trends 2026.

Exploration of how vertical AI is reshaping the AI ecosystem as competitive advantages migrate from model size to context and application.

Additional Resources

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI)

https://hai.stanford.edu

Comprehensive research on AI’s impact across society, including the annual AI Index tracking market developments and adoption trends. - Gartner Research

https://www.gartner.com/en/research

Industry analysis and predictions on enterprise AI adoption, including vertical AI implementation forecasts. - McKinsey & Company – AI Insights

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights

Research on AI’s economic impact and analysis of vertical versus horizontal AI value generation. - NEA Venture Capital – Tomorrow’s Titans

https://www.nea.com/blog/tomorrows-titans-vertical-ai

Investment framework and market analysis for vertical AI companies and specialized AI applications. - Turing Intelligence – Vertical AI Resources

https://www.turing.com/resources/vertical-ai-agents

Technical resources and case studies on building enterprise-grade vertical AI agents for specific industries.

Leave a Reply