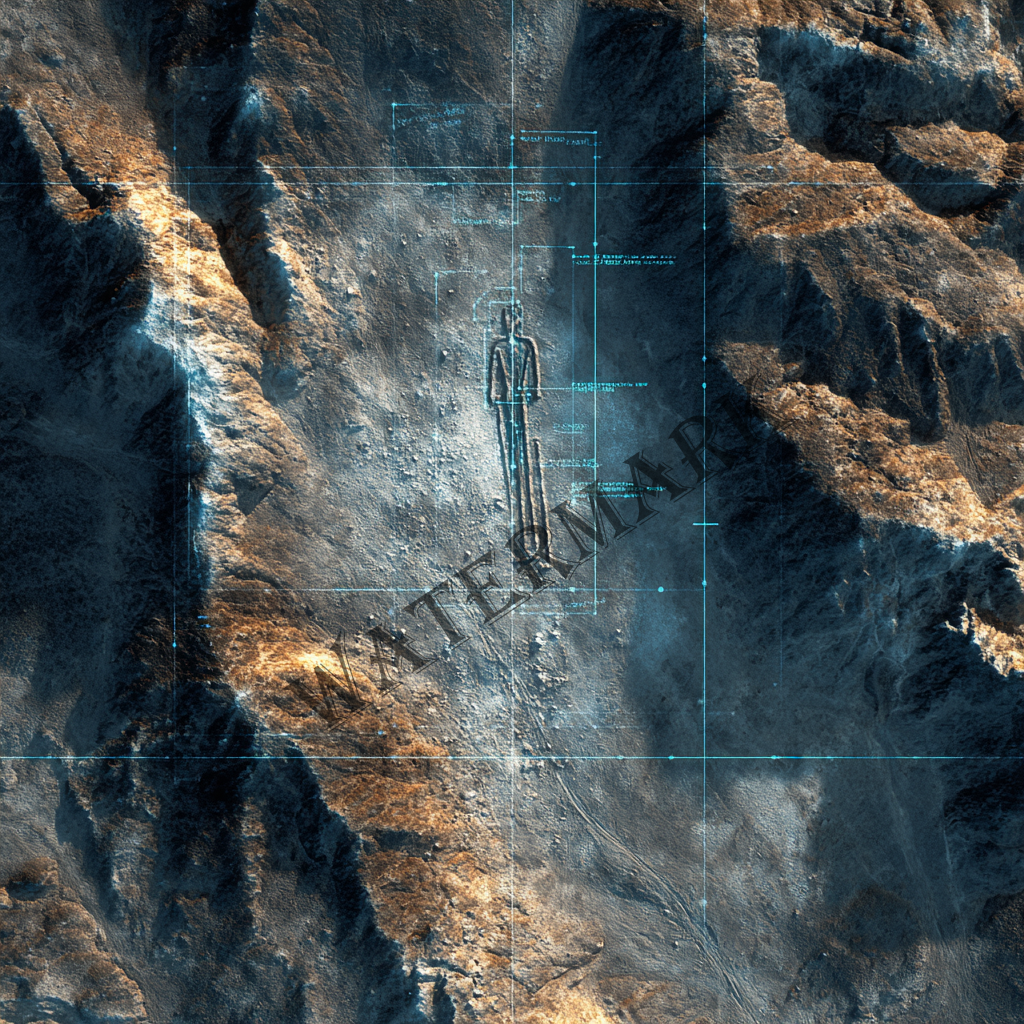

When satellite eyes meet machine minds, millennia-old secrets emerge from beneath jungle canopies and desert winds

The desert doesn’t give up its secrets easily. For nearly a century, archaeologists crawled across Peru’s Nazca Pampa on their hands and knees, squinting at the sun-bleached earth, hoping to spot the faint outlines of ancient artwork etched into the landscape over two thousand years ago. They found 430 figurative geoglyphs—mysterious drawings of humans, animals, and hybrid creatures that sprawl across the desert like a prehistoric art gallery. Not bad for a hundred years of work.

Then artificial intelligence showed up and found 303 more in just six months.

This isn’t science fiction. This is happening right now, in deserts and jungles across the planet, where algorithms trained to see patterns invisible to human eyes are rewriting our understanding of ancient civilizations. From the cloud forests of Ecuador to the mountains of Uzbekistan, from Maya cities hiding under Mexican canopies to medieval Silk Road settlements buried in Central Asian highlands, AI and advanced remote sensing technologies are pulling lost worlds into the light at a pace that would have seemed impossible just a decade ago.

Welcome to the golden age of archaeological discovery—where lasers pierce through jungle canopy, satellites map entire civilizations from orbit, and machine learning algorithms can spot a 2,000-year-old llama drawing that professional archaeologists walked past for decades.

Chapter One: The Revolution in the Desert

The Nazca Lines have haunted researchers since their rediscovery in 1927. These massive geoglyphs—some stretching over 1,200 feet across the Peruvian desert—depict everything from hummingbirds to spiders, from geometric patterns to scenes of ritual decapitation. They’re so large that many can only be properly appreciated from the air, which raises the delicious mystery: why would a civilization without aviation technology create artwork designed for a bird’s-eye view?

But here’s what really matters for our story: traditional archaeological surveys of the Nazca Pampa are brutally slow work. The region covers approximately 450 square kilometers of harsh desert terrain. Human researchers must examine high-resolution aerial photographs meter by painstaking meter, training their eyes to spot subtle changes in ground texture that might indicate ancient disturbances. Miss a shadow at the wrong time of day, and you’ve walked past a priceless artifact.

Enter Masato Sakai, an archaeologist at Yamagata University in Japan who has dedicated two decades to studying the Nazca Lines. Sakai understood that the traditional approach, while thorough, faced an impossible math problem: there simply weren’t enough human hours in enough human lifetimes to search the entire region with the care it deserved. The expansion of urban development was already damaging undiscovered geoglyphs before they could be documented and protected.

So Sakai did what any reasonable 21st-century scientist would do: he called IBM.

Together with IBM Research, Sakai’s team developed a deep learning model specifically trained to identify geoglyphs from aerial and satellite imagery. The AI wasn’t looking at images the way humans do—it was analyzing patterns in ground disturbance, changes in soil texture, subtle variations in how light reflects off the desert surface. It could process vast quantities of data at superhuman speed, flagging potential sites for human archaeologists to verify in the field.

The results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September 2024, were staggering. The AI system identified 303 new figurative geoglyphs in just six months of field surveys—nearly doubling the total number discovered over the previous century. As Sakai explained, the use of AI allowed his team to map geoglyphs with unprecedented speed and precision, a feat that traditional methods could never accomplish (France24, 2024).

But speed wasn’t the only advantage. The AI proved particularly adept at spotting smaller “relief-type” geoglyphs—figures created by piling or removing stones that are extremely difficult for human eyes to discern, even in high-resolution photographs. These smaller geoglyphs, typically measuring around 10 meters in length, had remained hidden for millennia simply because they were too subtle for traditional survey methods.

Among the discoveries: a 72-foot-long killer whale wielding a knife, depictions of decapitated heads, humanoid figures with elongated limbs, domesticated camelids, birds, and even scenes that appear to show ritual sacrifices. The whale with the knife isn’t just visually striking—it connects directly to Nazca pottery that depicts orcas as supernatural beings performing human sacrifice, offering tantalizing clues about the culture’s religious beliefs (Archaeology News Online Magazine, 2024).

The AI’s discoveries also revealed fascinating patterns about how the Nazca people used their geoglyphs. The larger “line-type” figures primarily depicted wild animals and were positioned near elaborate ceremonial pathways, suggesting they served community-wide ritual functions. The smaller relief-type geoglyphs, on the other hand, showed mainly human motifs and domesticated animals and were located near ancient footpaths, probably intended for individual or small-group viewing (Sakai et al., 2024). The Nazca Lines weren’t a single unified project—they were a complex communication system serving different social purposes at different scales.

Chapter Two: LiDAR’s Laser Vision

While AI was revolutionizing desert archaeology, another technology was transforming our ability to see through one of archaeology’s most stubborn obstacles: trees. Lots and lots of trees.

Light Detection and Ranging—LiDAR for short—works on a beautifully simple principle: aim rapid pulses of laser light at the ground from an aircraft or drone, measure how long each pulse takes to bounce back, and use that timing data to create an extraordinarily precise three-dimensional map of the terrain. Modern LiDAR systems can emit millions of laser pulses per second, and crucially, many of those pulses can penetrate gaps in forest canopy to hit the ground below.

The result? Archaeologists can now perform what one researcher called “digital deforestation”—removing all the vegetation from a landscape in post-processing to reveal the naked earth underneath, complete with every subtle bump, depression, and geometric anomaly that might indicate ancient human activity (Explorersweb, 2023).

The technology has proven transformative in Central and South America, where some of humanity’s greatest pre-Columbian civilizations built massive cities that were subsequently swallowed by rainforest. Traditional ground surveys in these regions are nightmarishly difficult—hacking through dense jungle with machetes, battling insects and heat, all while trying to spot archaeological features hidden under centuries of leaf litter and vegetation.

“A decade or two ago you needed to charter a flight just to hold all the equipment,” explained Nicolas Gauthier, a University of Florida anthropologist. “But now you can put the technology on a relatively cheap and lightweight drone” (Washington Post, 2024). This democratization of LiDAR has triggered an explosion of discoveries.

In Ecuador’s Upano Valley, archaeologists used LiDAR to map a dense network of interconnected cities hidden beneath the Amazon rainforest. The settlements date back at least 2,500 years—more than a millennium older than any other known complex Amazonian society. Stéphen Rostain, who directs investigations at France’s National Center for Scientific Research, described the discovery in almost mystical terms when he told reporters, “It was a lost valley of cities. It’s incredible” (Ancient Pages, 2024).

The Upano Valley sites reveal sophisticated urban planning: rectangular platforms arranged around low squares, distributed along wide streets, connected by an extensive road network that spans multiple settlements. Radiocarbon dating suggests these cities were occupied from around 500 BCE to 300-600 CE, roughly contemporaneous with the Roman Empire in Europe. At its peak, the region may have supported between 10,000 and 30,000 inhabitants—comparable to Roman-era London (GPS World, 2024).

“It’s amazing that we can still make these kinds of discoveries on our planet and find new complex cultures in the 21st century,” said Thomas Garrison, an archaeologist at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in LiDAR technology (Ancient Pages, 2024).

In Mexico’s Campeche state, LiDAR surveys revealed an ancient Maya city dubbed “Ocomtún”—Mayan for “stone column.” The site covers 50 hectares and includes several pyramids exceeding 49 feet in height, plus plazas and a ballcourt where Mesoamerican peoples played their mysterious ball game (Live Science, 2024).

Perhaps most dramatic was the 2024 accidental discovery by Luke Auld-Thomas, a PhD candidate at Tulane University. Auld-Thomas was analyzing publicly available LiDAR data originally collected for an ecological survey—data that had been sitting unused on a server. When he processed the imagery to remove vegetation, he found Valeriana, a massive Maya city containing over 6,000 buildings, complete with pyramids, plazas, a ballcourt, and a reservoir. The city had been hiding in plain sight, covered by jungle, while archaeologists focused their limited resources elsewhere (Triton Times, 2024).

The discovery of Valeriana highlights one of LiDAR’s most powerful features: the data it generates is permanent. Once you’ve scanned a region, that three-dimensional map exists forever on a hard drive, ready to be reanalyzed with better algorithms, studied by future researchers, or compared against later scans to track erosion and degradation. If climate change or urban development destroys the physical site, we still retain a perfect digital snapshot of how it looked when first scanned.

Chapter Three: Silk Roads in the Sky

LiDAR’s archaeological applications aren’t limited to jungles. In October 2024, Michael Frachetti, a professor of archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis, announced the discovery of two long-lost medieval cities in the mountains of Uzbekistan, revealed through drone-based LiDAR scanning at approximately 2,000 meters above sea level (CNN, 2024).

The cities—Tashbulak and Tugunbulak—thrived between the 6th and 11th centuries along ancient Silk Road trade routes. They challenge long-held assumptions that major trade networks avoided mountainous terrain. Frachetti’s LiDAR imaging revealed extensive urban settlements dotted with watchtowers, fortresses, complex buildings, plazas, and pathways. Tugunbulak, the larger of the two cities, shows evidence of dense settlement patterns and sophisticated urban planning.

Excavations at the sites since 2022 have uncovered extensive evidence of large-scale iron production. The entire region sits atop rich iron ore deposits and was once covered in dense juniper forests that would have provided fuel for smelting operations. Frachetti theorizes that these cities weren’t simply trade stopovers but major industrial centers exploiting valuable natural resources.

“These high-altitude cities acted as nodes in a network that moved power and trade through Asia and Europe,” Frachetti explained to Nature (Archaeology News Online Magazine, 2024). The Silk Road wasn’t just about the movement of silk and spices between China and the West—it was about political forces, economic networks, and centers of innovation in Central Asia’s mountainous heartland.

The project represented the first time LiDAR equipment had been used in Central Asia for archaeological purposes, generating some of the highest-resolution images of archaeological sites ever published. Radiocarbon dating indicates that both cities declined in the first half of the 11th century, likely due to a combination of political fragmentation, environmental factors, and over-exploitation of the surrounding forests.

Chapter Four: The Space Archaeologist

If LiDAR lets us see through trees, satellite archaeology lets us see through time.

Sarah Parcak, a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and director of the Laboratory for Global Observation, has pioneered the use of satellite imagery to identify archaeological sites from orbit. She’s been dubbed a “space archaeologist”—a title she embraces despite having to occasionally explain that she doesn’t personally go into space to gather data.

Parcak’s approach exploits subtle differences in how vegetation grows over ancient structures compared to undisturbed ground. Plants growing atop buried stone foundations won’t be as healthy as those in natural soil, and these variations show up in satellite imagery when you manipulate the light spectrum using specialized image processing. Think of it as archaeological Photoshop—adjusting contrast and color channels until hidden patterns emerge.

“There’s a real sense of urgency around site mapping and site detection just because coastal erosion, wildfires, tsunamis—large scale climate events—are impacting sites,” Parcak explained in an October 2024 Washington Post article. “As satellite technologies improve, we’re able to see new sites almost every day.”

Parcak’s techniques have identified potential pyramids in Egypt, settlements across the Roman Empire, and Viking sites in North America. But perhaps more importantly, her work has highlighted the devastating scale of archaeological looting accelerated by modern technology. Looters can use the same satellite imagery and remote sensing tools that archaeologists employ, making the race to document and protect sites increasingly urgent.

This urgency led Parcak to use her 2016 TED Prize—which came with a million-dollar grant—to create GlobalXplorer, a citizen science platform that allows anyone with an internet connection to help identify archaeological sites and looting damage in satellite imagery. By gamifying the discovery process and breaking images into millions of randomized tiles without location information, GlobalXplorer harnesses crowdsourced human pattern recognition while protecting sites from would-be looters (UAB, 2017).

The platform demonstrates something crucial: even in our age of AI, human intelligence remains irreplaceable for certain tasks. Computers excel at processing vast datasets and identifying mathematically describable patterns, but humans are still better at spotting subtle anomalies, making intuitive leaps, and understanding context. The future of archaeological discovery lies not in replacing humans with machines, but in combining human creativity with computational power.

Chapter Five: The Ethical Labyrinth

This brings us to the philosophical knot at the heart of AI-powered archaeology: just because we can find everything, should we?

Consider the dilemma: Every time we develop better tools for discovering archaeological sites, we also hand those same tools to looters, treasure hunters, and developers who see ancient artifacts as obstacles to progress or opportunities for profit. Publishing the exact coordinates of newly discovered sites can put them in immediate danger. But withholding that information contradicts archaeology’s foundational commitment to open science and public knowledge.

The Nazca project tackled this problem by focusing on geoglyphs that are already widely visible and difficult to loot—you can’t exactly slip a 200-foot hummingbird drawing into your backpack. But many archaeological sites contain portable artifacts: pottery, jewelry, carved stones, metal objects. Once looters know where to dig, they can arrive with shovels before archaeologists can mount proper excavations or install protections.

There’s also the question of consent and cultural ownership. When AI trained on Western archaeological assumptions analyzes sites connected to Indigenous peoples, who gets to control how that information is used? Many Indigenous communities have sacred sites they deliberately keep secret or have traditional protocols around site access and artifact handling. An algorithm that automatically maps and publicizes everything it finds could violate those cultural boundaries.

The Ecuador discovery illustrates this tension. The Upano Valley cities lie in territory traditionally inhabited by the Shuar and Achuar peoples. Catalina Tello, director of Ecuador’s National Institute of Cultural Heritage, emphasized the importance of including these Indigenous communities in studying the sites “because these people have safeguarded and cared for all these vestiges” (Cambridge University Press, 2025). The technological capacity to find sites must be balanced with cultural sensitivity about who has the right to study, interpret, and make decisions about those sites.

Then there’s the preservation paradox: AI can identify thousands of sites, but archaeological resources—trained personnel, funding, equipment—remain limited. We can find sites faster than we can properly excavate and protect them. This creates an agonizing triage situation where archaeologists must choose which discoveries to pursue, knowing that the sites they don’t prioritize may be destroyed before anyone returns to study them.

Climate change amplifies this urgency dramatically. Rising seas threaten coastal sites. Increased precipitation causes erosion. Wildfires consume vegetation that once protected ruins. The permafrost that preserved artifacts in Arctic regions is melting. Parcak framed it starkly: the race is on to document as much as possible before it’s lost forever.

Finally, there’s the question of what we lose when discovery becomes automated. Traditional archaeological fieldwork is slow and labor-intensive, yes, but that slowness allows for careful observation, serendipitous discoveries, and deep engagement with the landscape. An archaeologist walking a site for weeks develops intuitive understanding that no algorithm can replicate. When AI accelerates the pace of discovery 20-fold, do we sacrifice depth for breadth? Do we trade careful interpretation for raw quantity?

These aren’t hypothetical concerns—they’re active debates shaping how institutions like UNESCO, national heritage agencies, and research universities develop policies around AI in archaeology. There are no easy answers, only ongoing negotiations between technological capability, scientific responsibility, cultural respect, and practical constraints.

Chapter Six: The Future Beneath Our Feet

The pace of discovery shows no signs of slowing. If anything, it’s accelerating.

Sakai’s team in Peru has identified nearly 1,000 additional geoglyph candidates flagged by their AI system that remain unverified. In the Maya region, vast swaths of Central American jungle remain unmapped by LiDAR. Satellite imaging technology continues improving, with resolution getting sharper and scanning capabilities becoming more affordable. Machine learning algorithms grow more sophisticated with each iteration.

“AI excels at efficiently processing large amounts of data,” Sakai noted in his research, adding that the use of AI in archaeology will increase dramatically in coming years (BBC Science Focus, 2025). The technology is maturing just as the need for it becomes most acute.

But perhaps the most exciting prospect isn’t the technology itself—it’s how it’s changing the fundamental questions archaeology can ask.

Before LiDAR and AI, archaeologists were necessarily limited to sampling: they’d identify a few promising sites, excavate those carefully, and extrapolate broader patterns from limited data. Now, for the first time in history, we can approach something like comprehensive mapping of entire regions. We can see not just individual cities but whole settlement networks, transportation corridors, economic relationships, and how civilizations evolved across vast territories.

The Nazca research revealed that different types of geoglyphs served different social functions—the smaller ones for individual or small-group communication along footpaths, the larger ones for community-wide ritual activities. That insight only became visible when AI allowed researchers to analyze the spatial distribution of hundreds of geoglyphs simultaneously (Sakai et al., 2024). Previous studies could document individual geoglyphs but lacked the complete dataset needed to identify system-wide patterns.

Similarly, the Uzbekistan discoveries showed that Silk Road trade wasn’t just about lowland oases and mountain passes—it involved complex highland urban centers that were integral nodes in transcontinental economic networks. This finding fundamentally revises how historians understand medieval trade and cultural exchange across Eurasia.

What other paradigm shifts await when we can finally see the complete picture? How many lost cities are still hiding under jungle canopy, how many ancient roadways remain undetected beneath desert sand, how many settlement patterns have we missed because we could only study small pieces of larger systems?

“The real power of the technology is we’re able to ask different kinds of questions,” Parcak explained. “Archaeology isn’t about the finding, it’s about the finding out” (Washington Post, 2024).

The tools are ready. The questions are waiting. And somewhere beneath the earth—under jungle vines, buried in desert sand, hidden beneath agricultural fields—entire civilizations are holding their breath, waiting for lasers and algorithms to speak their names again after centuries of silence.

The age of discovery isn’t over. It’s just getting started.

Reference List

Ancient Pages. (2024, January 12). LIDAR discovers lost ancient cities older than any known complex Amazonian society. Ancient Pages. https://www.ancientpages.com/2024/01/12/lidar-lost-ancient-cities-ecuadorian-amazon/

Archaeology News Online Magazine. (2024, September). AI uncovers 303 new Nazca geoglyphs, including knife-wielding orca and alien figures in Peru. https://archaeologymag.com/2024/09/ai-uncovers-303-new-nazca-geoglyphs-in-peru/

Cambridge University Press. (2025). Lidar and lost cities: Examining the public presentation of recent lidar findings through news media. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 13(1). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-archaeological-practice

CNN. (2024, October 24). Lost Silk Road cities mapped using LiDAR remote sensing. https://www.cnn.com/2024/10/23/science/lost-silk-road-cities-laser-mapping

Explorersweb. (2023, March 2). Lidar: Revealing archaeology’s hidden world with a billion points of light. https://explorersweb.com/lidar-for-archaeology/

France24. (2024, September 24). AI research uncovers 300 ancient etchings in Peru’s Nazca desert. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240924-ai-research-uncovers-300-ancient-etchings-in-peru-s-nazca-desert

GPS World. (2024, January 22). Lidar reveals lost cities in the Amazon. https://www.gpsworld.com/lidar-reveals-lost-cities-in-the-amazon/

Live Science. (2024, April 27). 32 times lasers revealed hidden forts and settlements from centuries ago. https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/times-lasers-revealed-hidden-forts-and-settlements-from-centuries-ago

Sakai, M., Sakurai, A., Lu, S., Olano, J., Albrecht, C. M., Hamann, H. F., & Freitag, M. (2024). AI-accelerated Nazca survey nearly doubles the number of known figurative geoglyphs and sheds light on their purpose. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(40), e2407652121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2407652121

Science Focus, BBC. (2025, March 15). How we’re about to solve the world’s greatest archaeological puzzle. https://www.sciencefocus.com/planet-earth/how-were-about-to-solve-the-worlds-greatest-archaeological-puzzle

Triton Times. (2024). Lost Mayan city accidentally unearthed. https://tritontimes.com/62311/news/lost-mayan-city-accidentally-unearthed/

University of Alabama at Birmingham. (2017). Space archaeologist Sarah Parcak launches TED Prize wish: GlobalXplorer. https://www.uab.edu/cas/news/faculty/space-archaeologist-sarah-parcak-launches-ted-prize-wish-globalxplorer

Washington Post. (2024, October 8). New archaeology tools, LiDAR and space mapping discover lost cities. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/interactive/2024/archeology-discoveries-ai-lidar-lost-cities-ancient/

Additional Reading

- Parcak, S. (2019). Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past. Henry Holt and Company.

- Comprehensive exploration of satellite archaeology techniques and their applications in discovering and protecting cultural heritage sites worldwide.

- Frachetti, M. D. (2008). Pastoralist Landscapes and Social Interaction in Bronze Age Eurasia. University of California Press.

- Foundational work on Central Asian archaeology and the development of social networks across Eurasia, providing context for understanding Silk Road discoveries.

- Chase, A. F., Chase, D. Z., Fisher, C. T., Leisz, S. J., & Weishampel, J. F. (2012). Geospatial revolution and remote sensing LiDAR in Mesoamerican archaeology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(32), 12916-12921.

- Groundbreaking paper on LiDAR’s transformative impact on Maya archaeology and broader applications in remote sensing.

- Garrison, T. G., Houston, S., & Alcover Firpi, O. (2021). Recentering the rural: Lidar and articulated landscapes among the Maya. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 64, 101349.

- Analysis of how LiDAR technology reveals connections between Maya urban centers and rural landscapes, challenging traditional settlement models.

- Verschoof-van der Vaart, W. B., & Lambers, K. (2019). Learning to look at LiDAR: The use of R-CNN in the automated detection of archaeological objects in LiDAR data from the Netherlands. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 2(1), 31-40.

- Technical exploration of machine learning applications for automated archaeological feature detection in LiDAR datasets.

Additional Resources

- Yamagata University Institute of Nazca https://www.yamagata-u.ac.jp/en/ Research institution leading AI-powered discoveries at the Nazca Lines, with ongoing field surveys and publications on geoglyph distribution and preservation.

- GlobalXplorer by Sarah Parcak https://www.globalxplorer.org Citizen science platform enabling public participation in archaeological site discovery and looting detection through satellite imagery analysis.

- OpenTopography https://opentopography.org High-resolution topographic data portal providing free access to LiDAR datasets for research, including archaeological applications.

- Laboratory for Global Observation (University of Alabama at Birmingham) https://www.uab.edu/cas/anthropology Research center pioneering satellite archaeology techniques and training programs in remote sensing applications for cultural heritage.

- Washington University Archaeology https://anthropology.wustl.edu/research-areas/archaeology Research programs focusing on Central Asian archaeology, including ongoing excavations at Silk Road sites and applications of advanced remote sensing technologies.

Leave a Reply